This is a guest post originally written in 2017 by former Indian Residential School student, Canadian author and playwright, Mark DeWolf.

After remarks were made in the Senate Chamber on Tuesday, March 7, 2017 by Conservative Senator Lynn Beyak regarding the Indian residential schools, there has been a firestorm of criticism, condemnation and calls for her resignation. Here are some of those responses.

The Liberal Indigenous Caucus issued a statement calling her comments “ignorant and harmful.” Indigenous Affairs Minister Carolyn Bennett said the comments were “ill-informed, offensive and simply wrong."

Conservative MP Cathy McLeod, Opposition Critic for Indigenous and Northern Affairs, suggested the Senator should inform herself about the Indian residential schools, and added, “What’s important for her is to reflect on the comments, reflect on how her comments hurt people who are already struggling.”

NDP MP Romeo Saganash told reporters: “We’re talking about genocide here, and no one can say that there were good parts of genocide and bad parts. It’s like saying, ‘Well, there are some good sides to what Hitler did to the Jewish community’.” (This is the same Romeo Saganash who, as a student at LaTuque Indian Residential School, was a member of the school hockey team that was flown to Switzerland to play in an international hockey tournament, an experience that few Canadian youth could even dream about.)

Globe and Mail columnist Tabatha Southey wrote: “It’s difficult, times being what they are, for Canada to stand out in the Wingnut Olympics currently in full swing, but Senator Beyak seems determined to own the podium.”

NDP MP Georgina Jolibois said she was “sickened to hear the views expressed” by Ms Beyak in the Senate. Talking points that came from the Conservative Caucus said the Senator's comments were “disturbing and hurtful to the many survivors [of the church-run schools] who suffered the devastating effects.”

National Chief Perry Bellegarde of the Assembly of First Nations said: "It's disappointing that these misinformed attitudes still exist after all the work by First Nations and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to bring light to this dark chapter in Canada’s history.” (Mr. Bellegarde may not have read the entire

TRC Final Report, which includes material that Senator Beyak made use of in her speech.)

Judging by the headlines, what really got people riled was the Senator’s attempt to speak on behalf of "the kindly and well-intentioned men and women and their descendants ... whose remarkable works, good deeds and historical tales in the residential schools go unacknowledged for the most part, and are overshadowed

by negative reports.” The Senator added, "Obviously, the negative issues must be addressed, but it is unfortunate that they are sometimes magnified and considered more newsworthy than the abundance of good.”

Senator Murray Sinclair, the former Chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, had an immediate comment to make: “I am a bit shocked, Senator, that you still hold some views that have been proven to be incorrect over the years, but, nonetheless, I accept that you have the right to hold them.” (This is the same Murray Sinclair who, in a letter to the Calgary Herald on August 5, 2010, wrote: “While the TRC heard many experiences of unspeakable abuse, we have been heartened by testimonies which affirm the dedication and compassion of committed educators who sought to nurture the children in their care. These experiences must also be heard…”)

Judge Sinclair was responding to a column by Calgarian Lea Meadows that appeared in the Herald on July 30, 2010, headlined "Residential schools generate anger but also pride." Ms. Meadows, who had worked in human rights and conflict management for more than 20 years, had written that both her mother and grandmother had attended Indian residential schools, and that her parents had taught at day schools on the reserves and at Indian residential schools. She wrote about “the deep hurt my family feels at finding their work routinely described as ‘abusive’ or ‘cultural genocide’, and said her mother told her that her days at Brandon Indian Residential School west of Winnipeg “included some of the happiest days of her life.”

Ms. Meadows went on to say of her mother: “Indeed, because of the education she received there, because of the support she was given by her teachers there, she was identified as a girl who could succeed at university. She did succeed.” After graduating from university, Ms Meadows' mother worked as a teacher on reserves in northern Manitoba. “[She] believed that she had been given a great opportunity by her teachers [at the Indian residential school]. She was determined to provide the same opportunity for other aboriginal girls and boys."

Ms Meadows' father was a United Church minister and a teacher at the same schools. “He too felt called to serve,” wrote Ms Meadows. “For my parents, this was not just work; those reserves were home. They lived in community with their students, the parents, and ultimately their friends. Between them, my parents spoke three aboriginal languages: Saulteaux, Cree and Ojibwe. They were literate in Cree sylabics.”

Ms. Meadows said she most definitely would not deny that great harm was done to a great many students in the Indian residential schools, and she stressed it how important it is to speak out against it.

But she also wrote, “To label the schools themselves and all who worked there as evil, and to describe everyone who attended a school as a ‘survivor’ is facile – and it dishonours those who were truly abused and did have something horrific to survive…. At the end of the day, I will not apologize for my parents’ service with and for aboriginal people. Indeed, I will defend it.”

And here is what Murray Sinclair wrote in response to Ms Meadows’ 2010 column:

“We [the TRC] will provide Canadians with a permanent record that weaves all experiences, all perspectives into the fabric of truth. [Lea] Meadows and others with the courage to step forward honour all of us. We are grateful.”

Anyone reading the Final Report of the TRC will find that it does indeed include testimony and other evidence that shows the residential school system as a complicated mix of good and bad, some of the “bad” stemming from attitudes and policies that Canadians in 2017 would not support, but which at the time were considered enlightened and sensible.

Some courageous indigenous Canadians have spoken out on behalf of the “good” done by residential schools. In her speech to the Senate, Senator Beyak quoted internationally-renowned Cree storyteller, accomplished playwright, novelist and classical pianist Tomson Highway who has worked compassionately with indigenous inmates over a great many years. A recipient of the Order of Canada, lauded by Maclean's magazine as one of the 100 most important people in Canadian history. Tomson Highway has said:

“It's the same with the [Indian] residential school issue.

“All we hear is the negative stuff; nobody's interested in the positive, the joy in that school. Nine of the happiest years of my life, I spent at that school. . .

“You may have heard from 7,000 witnesses in the process that were negative, but what you haven't heard are the 7,000 reports that were positive stories. There are many very successful people today that went to those schools and have brilliant careers and are very functional people, very happy people like myself. I have a thriving international career, and it wouldn't have happened without that school.”

In her speech, Senator Beyak said that Tomson Highway “has had little negative feedback from the indigenous community, because he also takes seriously the trauma of the residential schools for others. He worked for many years after university as a social worker, with broken families and inmates, mixing the challenges they face with the humour and spirituality of Aboriginal culture.”

The Senator's attempt to inject some balance into the highly-charged national discussion about the Indian residential schools has been met with a deluge of negative opinion and extreme language. She has been accused of equating IRS staff members with “well-intentioned and kindly” concentration camp guards in Nazi Germany.

A March 15 editorial in the Dryden Observer that dealt with Senator Beyak’s speech said, "Her comments are quite indicative of a generation that grew up much closer to this, who still see the many shades of gray in an issue that has grown black and white in the modern media landscape.” But the author then went on to say that the tales of horror should supersede "any attempt to rationalize or justify what happened as well-meaning.” He further went on to make a comparison between IRS staff and members of Hitler’s SS.

The blinkered view that many in the media — and as a result, many Canadians — have of the residential school system has not gone unnoticed. A highly respected historian whose book on Canada’s relationship with its indigenous peoples is often referred to by academics and commentators once wrote the following:

“[the story of residential school staff] is the sort of story that the country badly needs to hear. Sadly, whether or not it will listen is another question… I’ve long recognized that there is only a simplified, black-and white account that resonates with Canadians.”

In December of 2015, Cece Hodgson-Macauley, an indigenous columnist for Northern News Services and founding chief of the Inuvik Dene band, wrote in her column about her community’s reception of the TRC report:

“An Anglican minister apologized. It was all one-sided. So, of course many questions are needing to be answered, people are asking the big questions - with an investigation so huge and country-wide, how come we only hear one side of the story? “

Chief Hodgson-Macauley, who in March of 2017 was honoured for her work in politics by Indspire, an important Indigenous-led registered charity that “invests in the education of Indigenous people for the long term benefit of these individuals, their families and communities, and Canada”, went on to say in her 2015 column,

“The Truth and Reconciliation Commission is too one-sided. The real truth will come out.”

“The elders … are afraid to speak up and tell the truth. The truth will come out because people are not dumb. They will realize they only heard one side of the story.”

But attempts to present another side of the story have been made. The May 4, 2008, issue of the Calgary Herald contained a column with the headline "The good side of the residential school story is valid, too.” That column was written by celebrated Ojibway author/columnist Richard Wagamese who, as Canadians learned with sadness, died recently at the early age of 61.

On learning of that untimely death, National Chief Perry Bellegarde of the Assembly of First Nations tweeted that Wagamese “profoundly told the stories of our peoples.” One of those stories appeared in that Calgary Herald column, in which Mr. Wagamese said the Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School in Kenora had an overall positive effect on his mother.

“My mother has never spoken to me of abuse or any catastrophic experience at the school. She only speaks of learning valuable things that she went on to use in her everyday life, things that made her life more efficient, effective and empowered….”

Wagamese also said:

“As a journalist since 1979, I've heard people credit residential schools with the foundation for learning that allowed them to pursue successful academic careers. Others tell of being introduced to skills that became lifelong careers, and still others, like my mother, talk of being introduced to a faith that guided the rest of their lives.”

While he said it was absolutely necessary to document “horrendous experiences” and “soul-killing incursions”, he said it was also essential to hear from

“those to whom the residential school experience might have been a godsend, or at the least, a stepping stone to a more empowered future. Because those kinds of stories happened, too. They happened to my mother and others like her. To be brave and go against the flow, and tell Canada that for some native people, the residential school experience was not exclusively a horror show is to tell Canada that we have grown as nations of people, that we recognize that truth means a whole vision and not just a selective memory. If native people use this opportunity to show that they are capable of seeing beyond hurts and invasions and rampant disregard for our lives and future, we show our neighbours that the heart of us was never broken, that we were never conquered, that we have not and will never be assimilated, and that we have retained our dignity despite everything that might have happened to us.”

Wagamese concluded by saying,

“Tell all of the stories. The good along with the bad. Lead by example and use this opportunity to create harmony, to create a more balanced future for all of us. Such is honesty. Such is truth. Such is the foundation of forgiveness and such are the bones of reconciliation.”

If only all Canadians would read and heed Richard Wagamese’s wise and healing words.

But thanks to native leaders, certain vocal supporters of the Aboriginal cause, and, sadly, the media, words like these are not being communicated to the Canadian public. Terry Milewski, well-known CBC reporter, when phoned by a former IRS staff member who tried to point out that good things also happened in residential schools, said abruptly to her, “That’s not a story!” and hung up. Tabitha Southey, when taken to task for lampooning Senator Beyak, refused in high

dudgeon to even consider the possibility that the story of dedicated, kindly and, yes, well-intentioned staff members might have a place in the long and complicated fabric of the IRS system.

And there has been a good deal of distortion and manipulation of that story. Posts to the Wikipedia entry on the IRS system have omitted very relevant information and included highly questionable statements. An information kiosk at a TRC National Gathering actually stated that 150,000 children were compelled by the Indian Act to attend residential schools, a claim that is patently false. Similar statements have been repeated so often, they are now considered gospel truth.

Highly emotional language has been used to distort the facts. One frequently sees the statement, “They had their entire childhood stolen from them,” but while some IRS students were enrolled for as many as 10 years, the average length of enrolment during the entire IRS period was about 4.5 years, which means that just as many students only spent a single year in a residential school. Judging from the $26,000 average amount paid to former IRS students under the 2006 Common Experience Payment (CEP) made under the Indian Residential School Settlement — $10,000 for the first year of attendance, $3000 for every year beyond that — the average length of enrolment for former students still alive in 2006 was no more than 5.3 years. One can only wonder how the number of years enrolled was determined for the elderly and infirm applicants, who were not required to show proof of enrolment to obtain the CEP.

The claim that “150,000 students were torn from the arms of their family” is likewise specious, as a very large percentage — arguably the great majority — of IRS students were placed in residential schools by parents who either feared the legal consequences of not enrolling them or who wanted their children to get the “white man”’s education. In the last decades of the IRS system, parents had to complete an application form before enrolment took place. The picture painted in media reports of indigenous parents weeping as their children are dragged away is not totally inaccurate, as many have testified to that happening, but the emotional impact of such a scene has been used to distort the public’s perception of what actually went on in most cases.

The consequences of failing to put a child into a residential school have likewise been exaggerated and distorted in public statements. It is often claimed that parents who hid their children from an RCMP constable, Indian agent or school official faced “imprisonment”, when in fact the Indian Act of 1920 stipulated that a

parent who failed to enrol a child in school — any school, not just a residential one — was “liable on summary conviction before a justice of the peace or Indian agent to a fine of not more than two dollars and costs, or imprisonment for a period not exceeding ten days or both.” In 1920, $2.00 was the price of four pounds of butter — about $27 today.

The fact that an estimated 25 - 30% of indigenous children never attended school at all during the IRS period suggests that the threatened penalties was not taken seriously by everyone, and the number of indigenous parents actually jailed for failing to enrol their children in school is very low. Removing a breadwinner from a family and thus increasing poverty and community distress made officials very reluctant to apply the terms of the Indian Act.

The selection of photographs to accompany media stories about the residential schools further hammers home the narrative that all IRS students were unhappy captives in a cruel and repressive system. Images of sombre, even miserable looking children certainly capture some of the emotions that consumed many students in many residential schools, particularly during certain periods. But tellingly, photographs of students who look happy, well-fed and well-dressed — and a trove of such photographs exist in the fonds of church archives, if not elsewhere — only appear if the story focuses on attempts by Indian Affairs to paint the IRS experience as a beneficial and generally happy one for native children.

If there were happy IRS students, and if, as Senator Beyak claimed, there was “an abundance of good” in residential schools, why have so few statements in defence of the schools been made by former students? Two quite natural explanations come to mind. First, IRS “survivors” who have sensibly taken advantage of the one-time payment to residential school “survivors” — on average, about $26,000 each — are naturally reluctant to now proclaim “It wasn’t all that bad.”

Second, there can be very few indigenous Canadians who are not aware of the now-universal condemnation of the schools, and the way that “national disgrace” is being used to gain public sympathy and support in their leaders’ efforts to wring increased funding and other positive action from the federal government. Former students know how politically incorrect it would be to swim against the tide and possibly weaken their leaders’ negotiating position. Much has been said about the courage displayed by IRS “survivors” in telling their stories, but even

more courage would be required of an indigenous person who today wanted to say publicly, “Those were the best years of my life.”

If reluctance to come forward were not enough to silence those with positive stories, encouragement of negative testimony and suppression of “the good side” of Indian residential schools have also reduced the chances of Canadians hearing that equally valid “truth.” Ironically, the contempt heaped upon Senator Beyak and the fawning media coverage of the critics’s statements has brought testimony to the Comment section of some websites. In March of 2017, one person posting a comment to the National Post said:

There was a time I was working for the Church at a former residential school in northern Alberta. I’ll always remember an older resident coming up to me, telling me that the white lawyers had come into town, and they were all going to get lots of money for signing something against the residential school. Then, fifteen minutes later, he told me that he wished the children of the town could get the same good education that he had received at the residential school.

That comment was followed by another:

What we need is a real T&R inquiry, not a sham led by those who stood to gain by claiming that the schools were completely and unendingly evil.

And that led to this comment:

There was an off-reserve native woman interviewed on TV a number of years ago. She had received $40,000 as compensation for having attended residential school. She went on to say that had nothing but fond memories of her residential school education, and that although she did not need the money as she had a successful career, she planned to put the 40K in a savings account for her grandchildren’s education. Like you, I agree that the unending negative narrative is false.

The mendacity and the agenda-driven selectivity of those whose recent comments contradict what they themselves have said in other years does those individuals no credit. Self-righteous judgment, passed upon their fellow Canadians who, for the most part, are no longer around to speak for themselves, has been all too common, and that judgment has frequently been made by those who know only what they’ve been told by others, speaking not from personal experience, nor from serious research into the subject.

Those who have conducted research and reached certain conclusions from documented evidence face the enormous hurdle of getting anyone to consider their findings. In 2001, a National Post article by Richard Foot described the research conducted over six years by John Siebert, who at the time was working as a researcher for the United Church of Canada. According to Foot, Siebert’s research suggested that other, far more harmful causes than residential school enrolment lay behind the challenges currently facing indigenous communities in Canada. For pointing out that only a small minority of indigenous children ever attended a residential school, for suggesting that only a fraction of IRS students were forcibly removed from their homes, and for arguing that the system was therefore not the main cause of poverty and related social dysfunction among Canadian Aboriginals, Mr. Siebert was roundly condemned and his argument disavowed by the United Church. Tellingly, Mr. Siebert, who had been labelled a crank and a defender of the indefensible, went on to find employment in 2005 as Executive Director of Project Ploughshares.

The fact that the current distorted narrative about the Indian residential schools is now finding its way into schools should be of great concern. Just as children 60 years ago were given textbooks that extolled the early European explorers and Christian missionaries, and gave short shrift to the indigenous experience as colonial powers began invading the continent, students in today’s schools may very well be taught a similarly incomplete and biased history.

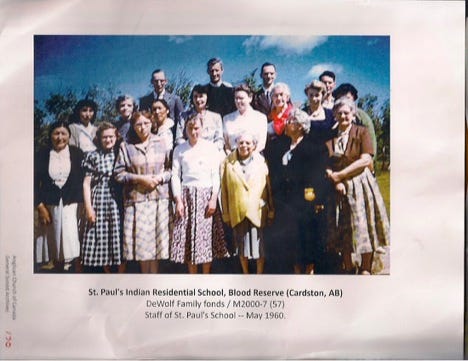

Attached is a photo of staff members at one Indian Residential School, St. Paul’s, on the Blood (Kainai) Reserve in southern Alberta. More than words can ever do, it reveals the kind of person who, not required to serve as nuns and priests often were, chose to take employment as teachers, supervisors and support staff in IRS institutions. The presence of several tribal members reminds us that there is a story there too.

Looking at the faces of these IRS employees from the early Sixties, one can understand why many former students remained in friendly contact with former staff for years afterward.

Mark DeWolf is a retired teacher of English language, literature and drama, living in Halifax, Nova Scotia. A playwright and musician, he supports Indigenous organizations such as Inspire and Reconciliation Canada, and whenever possible reaches out to Indigenous Canadians, particularly those whose family history includes enrolment in a residential school. He also attempts, whenever possible, to counter inaccurate or misleading statements about the IRS that appear in the media. His Blackfoot name is “Little Yellow Hair”. He maintains contact with members of the Kainai First Nation.

___

Thanks for reading. For more from this author on these topics, checkout - Why I Speak Out - by Mark DeWolf

The people of Canada including the Prime Minister his M.P,s members of the Senate news reporters and indeed all others who cry genocide have absolutely no idea off what the word means and i for one are very deeply offended by them having the audacity to talk of genocide.

My roots are Romany, my relatives go back hundreds of years and we have been held as second class citizens and persecuted for over a thousand years and this continues to this day.

Tens of thousands of my people were killed by Nazis & others all over Europe during WW 2, we were incarcerated at Auschwitz-Birkenau, Chelmo, Belzec, Sobbibor, Treblinka, Bergen-Belsen, m

Mathausen, Ravensbrook, and many other camps throughout Europe.

There were many Gypsies selected by Dr Josef Mengele for medical experiments and on one day alone Aug 2nd 1944 over 4200 Gypsies were gassed at Birkenau for one of the very few uprisings of prisoners against german brutality in the camp. That is genocide, how dare you use that term in this case that is a an insult to all races who have been subjected to it and you should be ashamed to use that term for your own personal gain.

Unlike all those self appointed experts mentioned in your article I can prove my case and feel that every single one of them owe me an apology, Oh yes and please realize that is ALL I want although am sure I will not get even 1.

How dare you.

Mark DeWolf is an indigenous or part indigenous man who writes expertly and provides a balanced but also banned perspective on residential schools. His essay is excellent and piercingly true.