Confronting Activist Myths: Decolonization, and the Spirit of the Times

Exploring the Nature and Technique of Oral Tradition in Folk and Indigenous Knowledge

By Shannon B Douglas

Everyone has an “Aunt Sally,” or a cousin, friend, or daughter who embodies the spirit of the lovable Phebe from Friends or the endearing but slightly less-than smart Penny from The Big Bang theory. If you’re like me, you can imagine her at the family gathering, jingling bangles talking about her latest detox at the Peruvian spiritual retreat; or about how the North Node conjunction in her astrology chart is why she has relationship issues. She’s like most of us at many points in our lives: well-meaning, searching for direction, and hoping to make a difference somehow, but Sally’s attempts to form an accurate map of territory are often comically lacking. We humor her eccentric attempts to find enlightenment, and we see them as mostly harmless, but it seems today, well-meaning as they are, some of the Phoebes and Pennies and Sallies are possessed by a bitter geist.

I tease about Sally and her superstitions because I’ve always been curious about things like astrology. I think there is an argument that practices like these were genuine attempts to preserve wisdom and knowledge in times before writing, and I believe we dismiss them because we’ve forgotten where they come from and how to understand them. We’ve forgotten the superstitious roots of the word geist, for example, which gave us the words “ghost” and “yeast.” I borrow this from Carl Jung, who suggests a geist is a certain type of active, even alchemical force, animating and fermenting things in the world. At one time they were seen as a living spirits and animistic forces. So, for us humans, zeitgeists, which are spirits that have captured generations and given them coherent stories, can be understood as personified social influences, with a specific personality animating social change. This kind of force comes alive and grows, a contagious impulse that spreads through populations via thoughts, collective beliefs and through stories and narratives about the world. Geist stories tell us that sometimes they come as helpful spirits of creativity while other stories and myths warn of the arrival of more difficult shades.

The spirit of our current times gives Sally license to claim moral, almost religious superiority, and permission to punish and silence people who shake her beliefs. Our once lovable, mostly harmless Aunt has found a creation myth that says the world is a place full of evil-doers and oppressive automata. She believes she must convert people to fight the existential threat. She must attack the wrong-believers and destroy the totems of their beliefs. She traffics in shame fests and saccharine sanctimony, chanting guru mantras about the need for “equity,” and “decolonization,” and about the evils of “white supremacy.” Her tendencies to seek trendy spiritual modalities and her penchant for adventures questing a clean colon have become puritanical. Now she insists on land acknowledgements at family gatherings instead of (patriarchal) grace before the holiday bird.

When this was just a fringe influence, no one paid attention, but Sally pushes her ideas about decolonizing math and science, and about the bigotry of biology in major universities. She demands we act on her desire to center “Indigenous Knowledge” in every government, workplace, and educational setting; and seeks to extract confessions in her inquisitions. Even though we’ve indulged her up until now, it’s time to have a serious conversation about boundaries, and the impact of the kinds of stories we accept from this bitter geist. We need to give Sally a new cosmogony to release her from this possession.

This is a medicine story. It’s a deeper account of the nature of the world than Aunt Sally and so many others captured by this ill-tempered Jinn, can narrate. I’ve been exploring and contemplating ideas about Indigenous Knowledge and the nature of oral tradition from around the world for decades. I cringe when I hear woke Sallies talk about traditional ways of knowing, venerating supposed Indigenous knowledge keepers. I have seen and lived the encroachment of modernity upon tradition in my short lifetime. I’ve also been taught stories about the nature of classes of spirits, like geists. As far as I know I have no indigenous blood, but the types of traditional folk knowledge that Sally opines about, like of the classes of spirits known as geists to the Germans, and as Jinns to the Persians, is only a few generations from any of our memories.

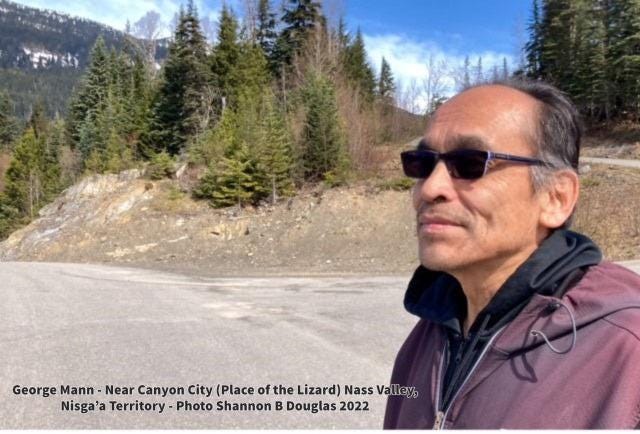

To approach this properly I share an opening prayer, a sacred orienting myth. I share it on behalf of the humans who have lived from the land and sea since the dawn of time as I was taught by my friend George Mann, a traditional artist, painter, carver, storyteller, and Knowledge Keeper of the Nisga’a Nation. It is an homage to a way of living and a spirit of relationship to the environment lost to time, replaced because of the encroachment of another spirit particular to humanity, a spirit of curiosity, growth, invention, and a collective motivating desire that our children have a better life than the generation before them.

It's also a protest and a criticism against Sally’s stories about white colonizers, her increasingly grotesque custom of land acknowledgements and the vile racialized ancestor guilt that she assigns to people based on shallow stereotypes, and I share this as an objection to the profane myth she tells herself about where we come from and how we got here.

This prayer has a simplified but universal structure found in the roots of tradition around the world. It’s a psychology using archaic language that frames how we relate to spirits around us, situating us within a cosmological framework, nesting the figure of the individual within the ground of family, environment, and the technology of the times. What I mean by this is that humans before modernity, who lived from the land and the sea, and who relied on what we dismissively call folktales, who used oral traditions to guide them through time, made very similar invocations before sacred ceremony and storytelling to continually situate themselves within their culture and their customs.

In the short scores of decades of true modernity, which has brought humanity to a peak of our technological flourishing on this planet so far, we have forgotten our relationship to our environment and to our humanity in ways we can barely comprehend. Shared creation myths orient us within a collective identity, and thinkers like Gaza Roheim, Joseph Campbell, Carl Jung and Marie-Louise Von Franz argue that not only do creation stories have a sense-making function, shared sacred stories describe adaptive biological, psychological and evolutionary mechanisms. The name of the Greek Titan Prometheus for example, the creator spirit of man and woman, and the giver of fire, means “forethought.” His story reflects the evolutionary development of the prefrontal cortex and our capacity to understand cause and effect and the consequences of our actions. He gave us the godlike ability to plan the future, he is a personification of our cognitive capacity for planning and forethought. Stories of the goddess Aphrodite narrate the stories of womanhood, of fecundity, fertility, and maternity. An opening prayer in this case is an attempt at a unifying story and in the spirit of another titan, Mnemosyne, the personification of memory. It is an invitation to remember a way of knowing common to all humanity.

I thank The Creator, Father God, and the Great Earth Mother, Goddess who sustains us all, who emerged from the cosmic egg, and from whose sacred union, the Heiros Gamos, births the world. I acknowledge the life-giving Sun and subtle influence of the Moon; I invite the spirits of the four directions and the four seasons. I acknowledge my Spirit Guides, my better angels, my grandmothers and grandfathers, the generations who came before me, and all my ancestors in spirit.

I pray that today, as I share these words, and as make decisions and choices, that I am conscious of my impact upon my community and upon the generations who will come after me. I call upon the wisest of my ancestors and spirit guides to help me in these sacred choices.

I give thanks for the land I live on, and for the abundance of the harvests and for people who work to provide our food. I humbly acknowledge and give thanks that this land has been blessed by more than a century without war, strife, or famine. I am grateful for the blessings of peace with my brothers and sisters of all faiths, traditions, ancestries, and races. I am thankful for the wisdom and friendship of others with whom we walk so temporarily in the arc of time, as we share in that peace today.

For All My Relations.

Cosmogonies like this survive in living traditions and as fragments of myths and sacred stories from around the world. I expect practitioners of religious traditions may object to what sounds like paganism and ancestor worship. Materialists will scoff at the superstition. Activists will attack me for culturally appropriating concepts that sound Indigenous but the primacy of Male & Female creator god-forms, the practice of ancestor venerations and connections to personal spirit guides, are universal to premodern humans.

Today, instead of sacred prayers for guidance from our heroic ancestors, for the wisdom our highest human potential, for the courage to consider All Our Relations and the Seven Generations, Sally virtue signals. She blames so-called colonialism, settlers, and genocidal races for all the sins of the world and for the loss of cultures imaginary to her. She is ignorant about history and the encroachment of modernity, which has raised humanity out of almost universal and ubiquitous suffering, and she is in denial of the benefits of this spirit of human flourishing, which has been globally ascendant for centuries. For a pre-modern person like my friend George, and for me, one who has studied these sacred ways and remembered the lessons of my ancestors, Sally spits sacrilege, and her beliefs are so far from sacred traditional teachings that the only word that makes sense to describe them is “evil.”

I say this because the fundamental teachings of the traditional elders of Turtle Island are rooted in concepts of our common humanity, not in vengeance and bitterness, or race-based generational shame and guilt. Indigenous traditional people, who she claims to venerate, don’t promote a creation myth of a world divided into oppressors and victims based on skin color. The four colors of the Medicine Wheel, (Red, Black, Yellow, and White) symbolize the skin colors of the four great nations of the world. When we look at our common stories, these same four sacred colors were central to practice of the pre-Columbian Alchemists of Europe, who derived their understanding from Gnostic and Hermetic traditions from the first and second centuries. Those traditions themselves were rooted in the memories of the stone circles and medicine wheels of the pre-Roman Gaul, what we now call France, Portugal, and Spain. We can’t know for sure if there was a connection, but it appears that pre-modern tribes of the ancient White-Nation Celts had common stories with Red-Nation people about the four nations, the four winds, the four seasons and the spirits of the East, South, West, and North.

People who keep the stories of the Medicine Wheel, acknowledge without judgement, the great history of mankind and the pattern of the cyclical rise and fall of empires and ages. This is not measured in decades or centuries, it’s a set of stories measured in millennia. Embedded within the stories of the wheel is a deep understanding that the blood of humanity is always red, that we are and have always been one race under the sky, and that the tides of humanity have ebbed and flowed for all of history. If we sincerely wanted to bring back indigenous knowledge and to decolonize our minds, we would recognize the medicine of forgiveness that has common roots in the new world and the old. Superficial Sally is stuck on grievance and on a language of justice that is even older, the justice which prescribes ancestor guilt, and eye-for-eye vengeance.

I met George twenty-five years ago while he was painting a mural of traditional Nisga’a totems on the wall of a cafe in Vancouver. I had been exploring religions and philosophy for years and I asked him to tell me some of his stories. The medicine he shared helped me to transform my life and more than any other person I’ve met, helped me to connect to what my friends from other traditions call God, Allah, Yahweh, Brahman, and Great Spirit.

Today George lives from the land and the sea in his ancestral territory, from traditional harvests of Oolichan, Sea Lion, and Salmon, using traditional methods of grease production, fat-rendering, and smoking. His foray into the modern world in the 90s, when we met in Vancouver, took him away from his role in his nation, that of being the living embodiment of the memory of the land and tradition, something the Romans once called a Genius Loci - a Spirit of the Place.

George’s traditional name, inherited much like a royal title is conferred in the blue-blood families of Europe, relates to the story of a volcanic eruption that destroyed more than twenty Nisga’a villages four hundred years ago. His name translates like a scene from a movie: “The Black Timber Wolf coming through the alders, leading the fleeing animals across the creek ahead of the fire and the lava flows.” His name also refers to a specific place in his territory, and a specific time in history. He inherited his name from an ancestor, and the people of his family each have a name that relates to another scene in the natural disaster.

In more traditional times, when the Nisga’a gathered in their winter houses, living from the food animals and fish they harvested and preserved, they told the story, and shared the warning signs of disaster, in an unbroken perfect oral memory stretching back four hundred years. They did this by simply saying their names in the right order, unpacking as they went: the character of Black Timber Wolf; the stories of the twenty-two villages buried under lava flows in the valley; and the tales of the sacred storytellers lost along with their medicine, each one’s death a tragedy as if a great library had burned.

I visited George this spring in his home village of Gitlaxt’aamiks in the Nass Valley of British Columbia because my two decades of meditations on the things he taught me led me to write a book exploring the nature of the soul and our relationship to what we in the west call Psyche and Logos. We spent a day touring the land of his nation and talking about our lives in the time since we had last seen each other. Both of us had raised children, lost loved ones, overcome obstacles, & dealt with hardships. These are the same things of life for people of all nations. A father’s grief at the loss of a relationship with a child, the slow dharma years of caring for an elder who could not live on their own, the struggles against nature and economy to provide honorably for a family. We brothers, have both wizened in years enough to know that illness, incapacity, suffering, and strife are life’s norms, and that brief happiness is the but the exception to the realities of living.

From Ottawa, I made my way to The Nass in Northern BC, a place inside the Alaska Panhandle, because I wanted to thank him for inspiring me and to seek his blessing. I felt I needed to be sure I had been respectful of his stories, and I am satisfied that the words I wrote and the words I am sharing now are from my true heart in a way that honors his traditions. He, my honored brother, my bonded brother, my Wak.

Indigenous Knowledge is uncomplicated and naturalistic. Much is the experiential knowledge about fish runs and survival techniques and the seasonal weather. Some is related to craft traditions, some to the hunt and the harvest, and some to the making of tools, weapons, and canoes. But some also is related to sacred creation stories, to Medicine, to the numerous supernatural spirits known to the Nisga’a. The mnemonic techniques and structures that people who practice oral tradition use to pass wisdom and knowledge from generation to generation, however, are extremely sophisticated. Until the invention of writing, all knowledge in the world was kept this way and in our modern world it seems astounding to most of us that Knowledge Keepers could memorize bible-length sets of stories and recite them word-for-word as they passed them down through generations from mouth to ear.

There is a living practice in the Muslim tradition to memorize the Koran like this and these arts are not long from our western tradition. We can see them in fragments of children’s songs, like “pocket full of posies” that date to the black plagues of Europe, artifacts in the archaeology of collective memory.

The Brothers Grimm we among the ethnographers who collected these relics of western oral tradition in the 1800’s. They discovered stories that had been kept alive and intact by knowledge keepers and storytellers for centuries before modernity and literacy began its encroachment into remote European hamlets. People like the Grimms, curious and concerned that traditions and languages were being lost with changes in technology and mobility, made sure to preserve those old stories by documenting them before the advancing spirit of growth and technology absorbed them.

It became a wonder to them that they could return to a village years after interviewing a storyteller, and hear stories they’d recorded, recited verbatim again by people who could not read or write. These storytellers would stop themselves mid-sentence and correct specific words in their recitations, the same phenomenon I witnessed with my friend as he unpacked stories of his nation with me. As George relayed some of his stories this spring, he would make parenthetical references to characters or spirits in the shorter narrative, as if referring to a link to an article a social media post. He would say, “that’s a story that takes three nights to tell” or “that’s a story that takes a whole day.”

One of the sophisticated ways of remembering culture for traditional people of the west coast is through carved Totem Poles which can stand a century or more telling their stories for all who know how to read them. We could think of a Totem Pole as a story in a single sentence AND simultaneously a mnemonic method of storing sophisticated concepts and lessons. Totems and sub-totems contain archetypal stories of people, clans, and nations, of obstacles, events, and heroic transformations.

When we think of the complexity of a totem pole, we might imagine a series of books like Harry Potter lined up in sequence on a shelf. We could say in summary that Harry Potter is about a young wizard growing, learning to master his evolving powers undertaking a series of adventures that transform him and the world he lives in. Yet we can take down each book and see that it’s divided into chapters with a heroic plot structure, and we can read them sentence by sentence, paragraph by paragraph. Such is the depth and richness of oral tradition, not just of west coast Indigenous people, but of all premodern humans who transmitted knowledge from mouth to ear over generations. George and I spoke at the foot of one totem pole he and another artist had carved over a period of more than a year. It was a replica of another pole that had once stood in the nation, containing forty-two stories that collectively take more than a week to tell.

These symbols are only able to retain their meaning however because people living in the environment, engaging in the traditional ways of life and custom, understand them because they’re embedded within the place, within the environment, within the custom and within the language. The context of location, natural environment, ecosystem, geography, and history cannot be separated from the meaning of these stories in many cases. The power of the story of the black timber wolf crossing the creek ahead of the flames of the eruption is lost when the people no longer live from the land, nor travel the valley by foot, and when these locations with their living spirits are only glimpsed from air-conditioned vehicles driving by at eighty km an hour.

One could grieve that as modernity encroaches, as technology like aluminum boats, synthetic nets, mass-produced rifles, and cellular phones moves into the villages, that the need for sophisticated mnemonics and storytelling diminishes. Marshall McLuhan notes a similar lamentation in the classical age, that as the art and technology of writing externalized the memories of the ancient storytellers, that humanity lost an art of engagement with the world, that we lost a way of thinking and being. “The Alphabet is an aggressive and militant absorber and transformer of cultures," he said, and today, even as some of the Genius Loci hold onto the old ways, the spirit of technology and modernity advances relentlessly.

“Plato was speaking of the oral traditions before it was modified by literacy. He saw writing as mainly a destructive revolution. Since then we have been through enough revolutions to know that every medium of communication (and technology sic.) is a unique art form which gives salience to one set of human possibilities at the expense of another set. Each medium of expression profoundly modifies human sensibility in mainly unconscious and unpredictable ways.” (Marshall McLuhan - “Joyce, Malarme and the Press”)

McLuhan believed that our media technology, evolving from oral tradition in the auditory environment, to script and writing, to the printed word, and into the electronic age of radio, television and the hyperconnected global village is all an extension of man, like Campbell and Jung believed that myth and story are extensions of biology. Because of these evolutions however, McLuhan observed that, “when the ground changes, the figure(s) may disappear.” When the technology and information environment evolve, old stories lose their relevance and meaning. Who needs to spend weeks harvesting oolichan and rendering their grease when bananas from the Caribbean, strawberries from California, and olive oil from Italy are available in the cash economy?

Lamentations of changes to culture, society and environment are sentimental and nostalgic and fail to recognize a universally human archetype. The massive changes to the world in the last two centuries have come from the spirit of our eternal human curiosity, our drive to ask questions about the nature of existence, our competition to expand our knowledge, the human spirit of growth. But each advancement has come at a cost. The printing press which drove the Gutenberg revolution also drove the downfall of the monopoly of ideas that the church held for centuries in Europe. It democratized and distributed access to the Bible, allowing the common man direct access to the stories of the Old and New Testaments. In the 80s, video killed the radio star. The internet and social media are democratizing access to the sum of all knowledge in the world; but without contextual frameworks, and with algorithms capturing our attention, its driving conflict and animosity, destroying our ability to communicate with each other and isolating us from the world. It threatens the stability of our society and some now fear that Sally is leading us towards wars of tribe against tribe again. Today, our information environment gives space to unscrupulous storytellers narrating false realities for their own gains. It props up and validates Aunt Sallies, whose luxury beliefs lack the understanding of the underlying psychic structure and purpose of sacred stories about who we are and where we come from. These Sally stories pit tribe against tribe in violent and even genocidal ways. We would not wish these experiences on anyone, so the lessons of these wars are important but the brutality and the generations bearing memories of these traumas are best lost in. We should remember the implicit warning, if we view George as a Medicine Man, though he rejects the title: if we acknowledge the spirits and see sacred storytelling and invocations as types of shamanism giving frame to human meaning and purpose, then false histories manipulating audiences and stirring conflict can be seen as forms of black magic.

My ears popped as George and I drove the steep switchbacks from the high Nass to sea level taking us 1,700 feet down to the edge of the fjord. On the way he told me about the violent and bloody battles between the Nisga’a, the Haida and the T’Ling’t that raged for centuries. A similar story came to me from a Haida fisherman in the spring who was grateful that modernity has helped to bring lasting peace because the Haida, the Nisga’a and the T’Ling’t still remember the times of war. When one nation had bad years of harvest, they would raid the villages of other nations, much like Viking sailors would pillage others along their frontiers. The following year, their enemies would raid two of their villages in revenge, and the next year the Haida would raid three, or four in escalations. Before long, great wars were fought, and thousands of lives lost. On the seashore near a place called the island of skulls, George told me the place was named for the enemies who lost their heads as they attempted to defeat the Nisga’a to control the Oolichan grease trail. The Nisga’a warriors mounted the heads of their enemies on pikes at the site the battle as a grisly reminder to the warring attackers to not come again. In another battle, stories tell us that 10,000 T’Ling’t died in a great battle, reminiscent of the war stories between Viking raiders and peoples of the lands they attacked.

Beyond these tales of wars, of bravery, pillage, valor and loss common to human history, among the various types of disappearing stories George keeps for his people, are the Medicine Stories and metaphors. These are stories of healing, of innovation, of leadership and transcendence. We see some of these in the European Grail Legends, about the quest for peace among warring tribes, accounting the efforts of a legendary king who embodied the spirit, the virtues, and the capacities for unification instead of conflict. These romances narrate the spread of a new spirit of unity among tribes who found a way to tell better creation stories that integrated more and more people under a new code. In those legends we hear tales of quests for healing, immortality, heroism, and a relationship with honor and with God. They are not unlike the stories my friend keeps.

George keeps medicines of transformation and healing, of the individual overcoming the sins of others, of forgiving the self, of healing the spirit polluted by human evils. The types of stories kept by traditional people like George and other carvers were once so valuable that those who had been initiated into the totems and the sacred medicines were sought as war captives to be exploited for knowledge and technology. They were sometimes enslaved and sometimes traded for ransom. We could almost think of this in analogous terms to modern industrial or corporate espionage - except instead of a thumb drive or a micro-dot, or encrypted files, the sacred and valuable knowledge was stored in the minds of living people. These were wars to control information and knowledge at much simpler scales than today.

Modern activists increasingly control the stories in our major institutions. Sally demands we respect what she calls traditional knowledge in the name of decolonizing our minds from our white privilege. She has declared a narrative war, fighting, it seems for us to return to earlier times with the incursive enemy being modernity itself, unjustly pillaging a traditional way of life. When we consider Sally’s aggressive and guilt-laced demands to return to traditional indigenous ways of knowing, we can see demands for a complete rejection of modernity itself. If we follow the premises of this movement, it lays a path to a place no less gruesome than the escalations of nations raiding increasing numbers of villages every year and we can see this in no other terms than as demands for an rejection of modern life on a scale grander than any luddite could have ever imagined.

A recent article about the new Director of Indigenous Science at Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC), a Federal Government department, illuminates a definition of this epistemology and makes the claim for its inclusion is this department with equal respect to western science:

“Indigenous Science is about the knowledge of the environment and knowledge of the ecosystem that Indigenous Peoples have,” she explains. “It is the knowledge of survival since time immemorial and includes knowledge of plants, the weather, animal behavior and patterns, birds and water – that is how they survived.” (Dr. Myrle Ballard)

This is an unsurprising claim that requires no government department to understand and to implement. All we must do is surrender all the trappings of the western world, give up our tools, technology and medicine and return to the land. We return our children to unsupervised play, return our women to the tasks of the home, of the village, and to the monthly visits to the moon lodge. Must we return the men to the hunt and the sea harvest and the vicious wars with bone-tipped spears and stone adzes? Some of us, assigned colonial identities by Sallies detached from reality, still remember these things because we lived them, or because our cultural memories and tales of wisdom keep them fresh in the field of meanings in which we are embedded. As much as these activists attempt to compel us to believe in an idealism of a lost sacred Indigenous narrative with false stories, we are also asked to forget that for most of us, even in the west, have only recently entered modernity ourselves.

I was a free-range child. As the child of a civil-mechanical engineer I lived a life a bit like a military kid. I spent almost two years in a small fishing/oasis village in the Atacama Desert on the coast of Chile where most kids didn’t have shoes. I had just finished kindergarten when we moved there, and I went to the local school along with descendants of the Spaniards and perhaps some of the Indigenous of the Atacama.

We played in the desert, along the seven miles of white sand beach that stretched north from the town, in fields of shifting sand dunes, along craggy black obsidian dikes and sills, reaching like giant fingers hundreds of feet into the ocean. We foraged in tide-pools, dug for razor clams and turned over rocks in the desert uncovering the mysteries beneath them. This was the land of iguanas and giant condors.

The animals and sea-life all had stories. Sharks, Marlin, the Giant Tortuga. The tides had tales. We hunted scorpions and lizards with long cactus quills. We harvested abundant food from the ocean for our lunches, gutting fish with pocketknives, cooking them on small fires over driftwood, or simply prying abalone from the rocks, and chewing their tough, but sweet meat raw after rinsing them with seawater.

This was in the mid-70s and always in sight between the shore and the horizon were Japanese freighters and fishing vessels. I looked back on that village again when google earth became a tool to see where I once knew all the names of the flora and fauna, and all their personalities. Where I knew the spirit of the wasps that pollenated the black figs and the types of poisonous sea anemone and deadly cone snails. I read the abalone were all gone. They were harvested to near extinction for the global seafood markets. The local fishers who brought their catch daily to the docks, supplying the fish monger who walked around our neighborhood with a wheelbarrow of fresh fish on ice, all outmoded by modernity. The olive groves, the fresh artichokes, onions, and tomatoes that grew abundantly in the oasis, all fallen to the cheaper foods made available through global markets - overtaken by the forces of modernity.

My mother, along with her sisters and brothers grew up like this in Bonavista Bay in Newfoundland. The village was home to my ancestors for centuries. They had lived in the remote outport, often winter-locked for weeks from outside access, much like in George’s village. The menfolk drew subsistence from the sea. They knew the spirits of Moose and Rabbit and Seal. Those men, my grandfathers, and uncles, risked their lives in small boats to harvest cod to feed their families, exporting dried saltfish to trade with Jamaicans for rum and sugar in relationships so old, no-one remembered their origins.

The capelin and the squid once came into the bay by the tens of millions, harvested by local men from their dories that were hand built in the village, by those same men, in traditional ways of construction that had been passed from generation to generation. In my lifetime and in my memory, they had but to reach over the edge of the boats and haul fish by the bucket to bring the bounty of the ocean home.

I spent some of my young summers there visiting my mother’s home and learning how to prepare capelin for the drying racks and for the smoke house from my great grandfather. I learned how to clean the squid, how to salt them and hang them to dry in the air, in preparation for trade with the Chinese and Japanese markets. I learned how and where to collect mussels, cutting them from their clusters below the high-tide line with my pocketknife along the frigid waters of the bay where often giant icebergs passed.

Many of George’s stories reminded me of the changes that had affected my own ancestor’s villages in just the last century. The Grand Banks and the Cod Fishery were depleted decades ago, the seal, starving to population collapse, seabirds dying at sea for lack of food. The mighty tides of capelin, whose billions once churned the surface waters of the bay as they came to spawn, a fading memory of life before modernity.

On the banks of the Mighty Nass this spring, on Easter Monday, we met a fly fisherman, in hip waders, perhaps in his late fifties. He had walked down to the riverbed from his truck parked a hike away. He was there, with his permits to take a couple of Spring Salmon on barbless hooks, a true sportsman with respect for his harvest. He said he’d been fishing there for more than a decade, an isolated spot away from commercial exploitation. He understood something about the sacredness of the animals he was pulling from the river. It was an annual ritual for him to come to the Nass, to spend time alone, harvesting food for his family from the wilderness, the bounty of the Great Mother.

While we were talking two trucks hauling boats had driven down onto the riverbed and set out on the river with groups. “Illegal guides,” the sportsman told us. He was seething. He said once people learned of that secluded place, those people would tell others, and come again themselves and the remote wilderness would be crawling with people disrespecting nature and tradition and the gifts of the river. He’d grown up on the coast of Nova Scotia, in Mi’kmaq territory, his family tradition like George’s, like mine, outmoded my modernity, lamenting the loss of memories of way of life, forgotten to relentless progress.

George volunteered that the elders still told there had once been so many fish that you could walk across the river on the backs of the salmon. “I’m not angry,” he said. “People need to eat and there are a lot of people in the world now. This is the way of things.” This is the way of modernity, and of growing human populations, and technological advancements, invisible forces beyond any one man, beyond any one race, beyond any single wave of human progress.

In the time between our sacred conversations George spent nine years working in Alaska in the canneries helping to train locals on how to run the plants again. He had started work for BC Packers in Prince Rupert in the 80s, the largest fish-processing company in the world and had learned how to run and maintain the machinery. As global demand depleted the southern rivers like the Fraser over the decades, the search for more abundant fish stock moved north and the demand for staffing the processing facilities moved with it. There were already existing fish canneries and processing plants in Alaska, built with the same Japanese technology and global demand for fish that had driven the colonization of coast decades before, but they had fallen into disrepair because of labor shortages and George was called to help bring them back online. The Indigenous people of Alaska receive government benefits from oil and resource extraction leaving few in the local economy with an incentive to work. George, keeper of traditional Nisga’a memories, helped them remember the modern technology they had already forgotten until he was called home again to the Nass where they harvest Oolichan now in modern aluminum boats, with Yamaha engines using nylon nets.

So, what is exactly is this colonization our friend Sally prattles on about? And what is this Indigenous Science and tradition she valorizes? Three hundred years ago there were only 600 million people on the planet, and more than 90% of people lived directly from the land and the sea by the efforts of their own hands. Our population growth rate had been 0.04% for all human history up until then, limited by the natural phenomenon of high infant and maternal mortality and by early death to disease, dysentery, and infection.

In the 1800s we began to solve the tragic problem of infant and maternal mortality with advancing medical technology and expanding scientific knowledge. By 1800 we reached a population of one billion. In that century, the spirit of the scientific method brought us the germ-theory of disease, practices of sterility in medicine, complex urban sanitation, penicillin to fight infection, and by time of the discovery of insulin in 1922, we had reached two billion people. Life expectancy, which in Europe in 1890 was less than forty-five years for a working-class man, had almost doubled by 1990. Our explosive growth has come from saving the lives of hundreds of millions of infants and mothers; of extending those lives which before modernity were lost because of things we now consider trivial; sepsis, dysentery, pneumonia, accidents and diseases of the working poor. Two hundred years ago were not far removed from what Hobbs described of lives in primitive society, as nasty, brutish, and short, and today Sally blames whiteness, and capitalism, and science itself for what she sees as the genocidal spirit of human flourishing.

I asked George before I left, as we stood on the banks of the creek where the black timber wolf crashed through the alders, leading the animals of the valley ahead of the fiery volcanic flows, he, the living spirit and memory of the place, the Genius Loci, if there was another generation to take the sacred names and tell the sacred stories? Will the stories be forgotten because of the encroachment of settlers, and the gifts of technology that they bring?

Is this what Sally is decrying with her wails of decolonization? Did the evil spirit of white supremacy indeed visit itself upon the Red Nation who lived, like my parents, and my grandparents just two generations ago, by their hands from the fruits of the land and sea? Did the white European newcomers deliberately deprive the Nisga’a and the people of Turtle Island uniquely of their culture and way of life like Vikings pillaged and enslaved their victims? Is her attempted imposition of a new Creation Myth a false, self-serving representation of the spirit of the west? Is her story about our history a convenient lie?

The memories lost by George and his nation are like the ones the Vikings lost centuries ago as the spirit of trade replaced the spirit of raid, as the Christian Logos unified the coast and continent, for all its shortcomings, under a new unifying narrative. They are like the spirits lost to modernity in the abandoned out-ports of Newfoundland and in the sea once teeming with fish; like the traditional fishing villages of the coast of Nova Scotia where the sportsman grew up and the Mi’kmaq lived; like the oasis village on the coast of Chile where the Japanese freighters are still seen between the shore and the horizon, where the abandoned Inca roads still crisscross the desert.

I am afraid that no-one will take George’s name when he dies and I worry about the heirs of traditional stories. Will these stories so deeply connected to the sea, the rivers, the mountains, and the animal spirits of the Nisga’a valley find enough living memories within which to reside? Will be tell the same old story of tradition lost to new technology that the philosopher Plato lamented 2,500 years ago that was the same type of loss that McLuhan observed occurring as each iteration of new technology and medium of communication redefines the environment and the spirit of the world that we live in? Modernity has brought us all the gifts of the greatest flourishing in human history. In many ways we have fortified ourselves against the spirits of death and human suffering. We have conquered diseases and reigned in the spirit of war itself. We have established an entirely new story of humanity since the arrival of Europeans in the new world. Despite our prayers and grief for lost traditions and cultures however, despite Sally’s misapprehension and her misattribution of agency to the people of the White Nation, and her desire to bring forth an archaic spirit of justice, it is inevitable that as new mediums bring new ways of being; when the ground of collective technology and narrative changes, figures like my Wak, George Mann, will disappear.

He assures me however, even if this is the case, the Great Mother and the Spirit Protectors of the Four Nations will always ensure that the Medicine lives on.

For All My Relations

___

Thanks for reading. For more from this author checkout Legacy Media Cowardice & Impotent Woke School Boards Are to Blame. Please consider supporting Woke Watch Canada by upgrading to a paid subscription.

What a brilliant, educational, enlightened writer. To me, the central message is change is constant, new replaces old, and progress is evident in human history. While nihilists and critics of today’s world bray about the need to go backwards, as with the claptrap about decolonization, there is much triumph in human evolution, destruction as well, even from the printing press, but overall a world of better prosperity and more peace and less war and disease and starvation. The ancients knew less but pointed us in the right direction.

amazing article. I highly suggest reading William Wuttunee's 1971 classic Ruffled Feathers.