Listen to Residential School Survivors and Also Ask for Evidence

Michelle Stirling responds to the Times Colonist

On April 23, 2023, Charla Huber wrote an article for the Times Colonist about the history of Indian Residential Schools called, When it comes to residential schools, listen to survivors . Below is a response to Huber from Canadian journalist and regular Woke Watch Canada contributor, Michelle Stirling.

Listen to Residential School Survivors and Also Ask for Evidence

By Michelle Stirling

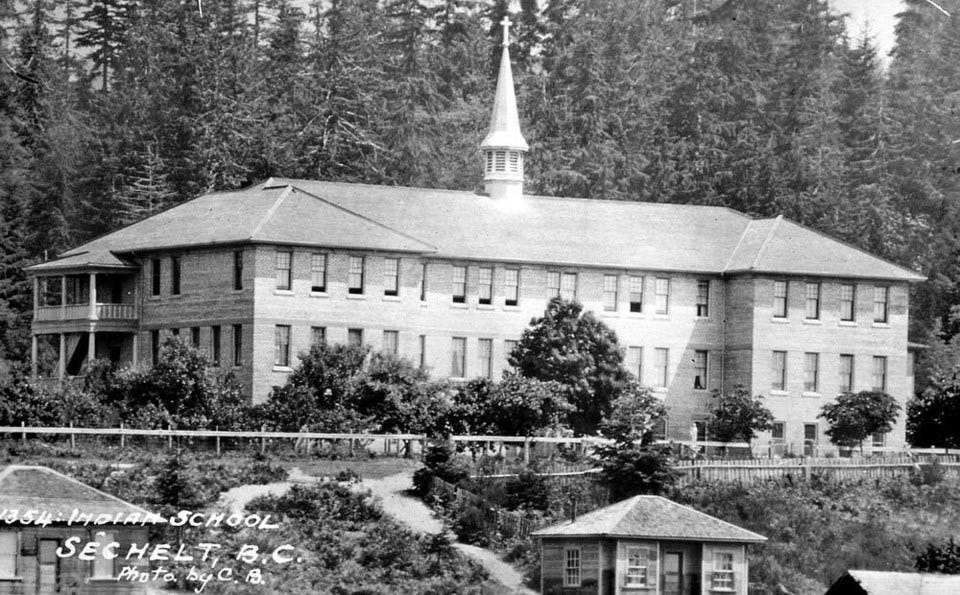

In the Victoria Times Colonist, Charla Huber wrote that the survivors of St. Augustine’s Residential School guided the search of the Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR). They say the GPR found 40 small disturbances which they believe are children’s graves, and that the GPR validates the findings. Charla asks us to listen to the residential school survivors and believe them.

One should always be respectful of elders and willing to listen to people who say they have been wronged or those who say they have special knowledge of events in the long past. At the same time, rule of law requires that once we have heard the statements, the claims need to be verified by evidence, particularly if criminal accusations are being made.

Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) can only locate ground disturbances, not bodies. It cannot tell what position anything might be in under the ground, thus when Charla Huber and Chief Lenora Joe add lurid details about children buried in a fetal position, we must discount such claims unless proven with evidence.

In her article, Huber escalates the find of 40 ground disturbances to say they are children’s bodies, inexplicably claiming “There is no good way to talk about the murder of young children.”

Murder? I don’t believe it.

I dispute this claim based on historical records. The federal government funded residential schools based on student count, so accurate attendance records were necessary. Likewise, bands were funded based on population numbers on reserve. When a child went to a residential school, the funds for supporting that child were directed to the school and not the band or family. When the child returned home, the funds were redirected back to the reserve and family.

Consequently, simply from an accounting perspective, the likelihood of dozens of graves of missing residential school children does not ring true.

Furthermore, in all these many years, we have not had murder charges filed by families or bands. It is true that children died at schools, most of tuberculosis (as did many more on reserve). Some children were buried in the school graveyard (not all schools had one), though others were buried in the community cemetery or on reserve.

There were also children who came to these schools as orphans, as did people in nearby communities as individuals seeking medical assistance or sustenance. Orphans who died at school may have been buried there. Their respective reserve communities would know that ‘someone’ did not come home, but the orphan had no one to come home to, and no one to tend to or care about their grave. But their death would have been documented according to Catholic practice and government regulation.

Robert Carney, eminent Canadian historian has written that residential schools served as the local social service and medical hub in the early days. So, it is possible there are unmarked graves of people who were not students at the school. However, it is an unfortunate leap of logic to suggest that GPR markings are graves of children who were ‘murdered.’

I don’t believe that. I also do not believe that children were buried in a fetal position in a shallow grave. First of all, Christians believe in the resurrection, and to this end, the human body must be treated with dignity despite its soul having left its mortal coil. The death registries for residential schools are detailed and many are also signed by the parents of the deceased child.

Secondly, in the time that children were allegedly buried in shallow graves, there would have been a large number of wildlife roaming around. Coyotes and other scavengers would quickly dig up a shallow grave. This is why graves are typically dug six feet deep.

I do believe that many residential school students suffered painful experiences – some extremely traumatic. We should listen, with compassion, to what they wish to share.

But we should not be misled by our sense of compassion to accept claims made by people about things that happened 60 or 70 years ago, without verification and evidence. We should pay particular attention when lurid details do not make sense and are presented to sway our emotions and shroud logical thinking. GPR scanning is not evidence of anything. What people understood as children, may be quite different from the facts.

We should be suspicious of people demanding that we believe them, while also demanding privacy; be suspicious of a band that provided preproduced video footage and interviews to give to the media but won’t let the media ask any questions. Be suspicious of people like Charla Huber who claim to have permission of Chief Lenora Joe to write her article, but who have no firsthand knowledge of those early days.

I am now an elder. Listen to me. Believe me.

In my own personal experience, I interviewed descendants of those who signed Treaty 7 – descendants of Chief Crowfoot, descendants of Colonel Macleod, and I interviewed Robert Patterson, at the time he was the last living Mountie of those early days. He joined the NWMP in 1876 and was stationed at Fort Macleod with those who made the 1874 trek West. Not one of them mentioned ‘residential school genocide’ or missing children. They all acknowledged the difficult sea change in the lives of aboriginal people at the time. They all stated that the Plains People were at risk of being poisoned into extinction by the American whisky traders. They all saw the threat of the US Cavalry crossing the border, bringing their murderous Indian Wars with them. Without the actions of Sir John A. Macdonald, the establishment of the NWMP (Mounties) and the Treaties, cross-border war would have been the result, especially after Custer’s Last Stand. Without arrangements for formerly nomadic hunter/gatherers to enter the agro-industrial society via education at residential schools, the Indigenous people of the Plains would have had no future at all.

Is it only my hearsay that I ask you to believe? No. This is all documented in a myriad of historical books and records of the time.

Yet today we see many well-educated Indigenous people, ironically claiming damage from that which protected their tribes from total destruction; ironically using the very literacy skills originally learned at residential schools. A further irony is that aboriginal languages had no written form. That aboriginal languages survive to this day is thanks to a handful of priests who captured and retained several aboriginal languages by creating syllabics, a kind of alphabet, for a written language. They also constructed bilingual dictionaries. Many priests were more fluent in aboriginal languages – their second or third language - than those Indigenous people of today who are lodging complaints!

One priest, Jean-Marie Lejeune, even developed a written form of a local language using a Duployan shorthand to represent Chinook Wawa. He published a local paper in it called the “Kamloops Wawa” from 1891 to 1900. Aboriginal people using Chinook Wawa were able to read and write in their own language as well as English and French via this clever shorthand method.

Let us return to our elders.

I spent many hours working with Dr. Dempsey when he was curator at the Glenbow Museum; he was my research supervisor.

Dr. Dempsey’s wife, Pauline Gladstone Dempsey, was a Kainai woman and daughter of Senator James Gladstone. She would have been in an Anglican residential school about the time the elders of the shíshálh Nation were in residential school on the coast. Though they were different schools run by different religious orders and different people, Pauline’s story gives some valuable perspective about residential schools in general and the context of the time.

So. I don’t believe Charla Huber, that’s for sure. If the elders would like to tell us their stories themselves, let us listen with respect. And let us comb historical documents for evidence. That’s what rule of law is about. Evidence, not hearsay.

END

Michelle Stirling is a member of the Canadian Association of Journalists. She researched, wrote, and co-produced historical shows about Southern Alberta under the supervision of Dr. Hugh Dempsey, then curator of the Glenbow Museum.

___

Thanks for reading. For more from this author read, Unmarked or Mass Graves? Epidemic or Genocide?

There are now two ways to support Woke Watch Canada through donations:

1) By subscribing to the paid version of the Woke Watch Canada Newsletter for - $5 USD/month or $50 USD/year

2) By donating to the Canadian School Board Investigation fund, which is raising money to expand Woke Watch Canada’s research and investigation into dysfunctional Canadian school boards.

I definetly think Charla Huber's article in the Victoria Times Colonist should carry a content warning such to advise readers that the content may elicit strong potentially harmful emotional responses from reading. Perhaps something like the following may be appropriate:

WARNING

The following article is based on a true story. Only the facts have been changed. The fictional content may be offensive or disturbing to some readers. Reader discretion is advised. Should any readers experience intense physiological or psychological trauma or symptoms you are advised to contact the Denialist trauma hot line at: 613-995-6403. Marc Miller is standing by to take your calls.

This is an extremely informative article. Indigenous people must be listened to, of course, but I agree with Michelle Stirling that evidence must exist, too - and she raises some interesting points.