Postcolonial Theory and Indigenous Traditional Knowledge

Linking Postmodern Identity Politics with Transitional Shifts in Canada’s Political Economy and Media Landscape

Introduction

On February 13, 1996 in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, Canada - Frances Widdowson and Albert Howard attended a federal environmental assessment review of Broken Hill Properties (BHP) - who were seeking approval for the construction of Canada’s first diamond mine. What held particular interest for Widdowson and Howard though, was the inclusion of a presentation, for the purpose of “assessing the impacts of the proposed mine,” of Traditional Knowledge by local aboriginal peoples’.

From Disrobing the Aboriginal Industry: The Deception Behind Indigenous Cultural Preservation:

“The importance of aboriginal peoples’ traditional knowledge was beginning to be recognized in international circles and within the Canadian government. It had become particularly popular in the north, and in 1993 the government of the Northwest Territories developed an unprecedented “Traditional Knowledge Policy” that directed government employees to incorporate traditional knowledge into all government programs and services.” -Frances Widdowson & Albert Howard

Widdowson & Howard described a scene at the BHP presentation where participants clapped and played along. But also, where it was clear that no one, not even the presenters, had any clue what was going on, or even what anyone was talking about. No one could answer the question: what are the methods of traditional knowledge and how do they compare to Western methods like science?

As part of the charade, representatives from BHP committed to investing in further traditional knowledge research, even though it was clear that no one present had the slightest idea what it was, or how it could help with environmental assessments of diamond mines. During the session, when Widdowson and Howard asked questions about methodology, they received a rambling disjointed response from Dene Nation chief, Bill Erasmus that included the following:

“...the scientific process we talk about is very complex. It takes a lot to describe…Without quoting experts in the field it’s hard to describe. It is a science. There’s a method to the way people work…We’ve managed to survive all these years. We can give you many examples. This is how society works.”

Widdowson’s and Howard’s take-away from the traditional knowledge portion of the review can best be summed up in their words - “Despite the expectations…and the praise…we were surprised when the technical session on traditional knowledge proved to be nothing more than a compilation of jejune platitudes interspersed with various intellectual dodges.”

If this is the case, then why would BHP, the Canadian government, or anyone else for that matter, want to promote and incorporate substanceless performative practices? Why do so many people think it's a good idea to include traditional knowledge in the creation/implementation of government policy? This essay aims to show the link between traditional knowledge and postmodernism, and to point out some of the forces at play resulting in the widespread adoption of non-science nonsense.

Allow me to close this introductory section by noting simply that business and governments have not always operated this way; they certainly have not always been so “open minded.” On that matter, this essay also aims to illustrate some of the important transitional shifts in political economy, communications media, academia and cultural attitudes, that help explain the circumstances Canadians find themselves in today.

Modern Times and Regimes of Accumulation

“I broadly accept the view that the long postwar boom, from 1945 to 1973, was built upon a certain set of labour control practices, technological mixes, consumption habits, and configurations of political-economic power, and that this configuration can reasonably be called Fordist-Keynesian. The break up of this system since 1 973 has inaugurated a period of rapid change, flux, and uncertainty.” -David Harvey

I wonder if Charlie Chaplin was more inspired or disturbed by what he saw in Detroit, Michigan in 1926 while receiving a tour of the famed Ford automobile factory from founder Henry Ford himself!? Ten years later Chaplin produced a cinematic masterpiece, the comedic, yet profoundly poetic lament, Modern Times; making a powerful statement that resonated with the disenfranchised working class masses subject to the inhumanity of the Fordist period of industrialization. A condition that for many reasons, could not sustain indefinitely.

In the book The Condition of Postmodernity, David Harvey discusses a “body of interiorized rules and social processes…called the ‘mode of regulation.'” These consist of “norms, habits, laws, regulating networks and so on” that ensure there is broad public cooperation toward a “unity of process.” The process, explained by Harvey, was undergoing a change - “a transition in the regime of accumulation and its associated mode of social and political regulation.”

"Regimes of Accumulation" refer to systems of production and consumption; "Modes of Regulation" refer to the written and unwritten laws of society relating to the Regime of Accumulation. As will be elaborated on throughout this essay, the transition from a “Fordist” regime of accumulation, to a “post-Fordist” regime of “flexible” accumulation, corresponds with the postmodern turn. These are related and pivotal shifts from which we are still feeling the repercussions.

“...Henry Ford’s methods, an thus Fordism, can be characterized as a “… production system that rested so heavily upon the socialization of the worker to long hours of purely routinized labour, demanding little in the way of traditional craft skills, and conceding almost negligible control to the worker over the design, pace, and scheduling of the production process.” -DH

An important distinction, relevant to these transitory shifts experienced by Canadians, is the disproportionate lack of participation in the labour force regarding the Indigenous, due to the incommensurate nature of Indigenous dispositions with the dehumanizing habits required under Fordism, means that Indigenous communities experienced the shift into “flexible accumulation” differently than non-Indigenous communities.

The quote below refers to Native Americans, but Canadian Native populations were also “hostile” to Fordism.

“Ford had relied almost exclusively on immigrant labour to set up hIs assembly-line production system, but the immigrants learned, and native American workers were hostile.” DH

The Four Stages of Indigenous-non-Indigenous History

The Four Stages of Indigenous-non-Indigenous History, as demarcated by the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples:

Separate worlds

Contact and cooperation

Displacement and assimilation

Negotiation and renewal

The current phase of “negotiation and renewal” began in 1969 with the Pierre Trudeau government's ”White Paper on Indian Policy.” Consistent with the postmodern turn, and from this point on, the Canadian government has rejected earlier policies that were aimed at assimilating the Indigenous population into Canada’s labour force; opting instead, for a descent into myth, where policy finds its roots in postmodern parallelist assumptions.

The next section stresses how Settler and Indigenous populations developed in an uneven fashion; the level of uneven-ness being different depending on which historical period.

Uneven and Combined Development

In her book Separate But Unequal: How Parallelist Ideology Conceals Indigenous Dependency, Frances Widdowson offers a critique of “The Final Report” produced by the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. The Final Report is considered a crucial knowledge source that greatly influences public policy regarding Indigenous issues.

In this section I outline some of the assumptions adopted by the Royal Commission which leads them to take an ideological stance, and thereby reject the body of scholarship that contradicts their position. It should come as no surprise that the assumptions the Royal Commission accepts, are thoroughly postmodern; less understood though, is that the general thrust of what they do not to listen to, is rooted in the reasoned analysis of material and historical facts.

My essay The Corruption Of Canada’s Indigenous Victim Industry, discusses the founding postmodern ideology underpinning the Royal Commission's stance on Indigenous issues, a product of cultural relativism known as parallelism; a pipe-dream involving Indigenous-non-indigenous living harmoniously in separate and distinct parallel societies. In this essay I lean on Widdowson’s work in Separate But Unequal to dig deeper into the assumptions that either support and/or create the conditions for parallelism.

Claimed to be drawn from the Indigenous “conception of history,” the Royal Commission's framework of “diversity and local autonomy” conceives of the levels of variations within European and Indigenous societies, at the time of contact, as “similar.” This of course ignores the obvious developmental gap present when European explorers, arriving in enormous and technologically advanced ships capable of traversing oceans, encountered Indigenous hunter-gatherers paddling canoes.

“The Royal Commission declares that developmental assumptions about the nature of differences between the Old and New Worlds are ‘false’ and indicative of racist attitudes that justify colonialism.” FW

The acceptance of parallelism requires that we ignore the developmental gap that existed at the time of contact, because it seeks to restore initial conditions when it was assumed that Indigenous peoples’ were independent. Although consistent with the Aboriginal Industry’s goal of gaining maximum autonomy, this ignores the reality of dependency that existed, for both Indigenous-to-settler, and settler-to-Indigenous (as will be explored in the next section). In order to pull off this rouse, the complexity of Indigenous economies, political structures, traditional knowledge, etc., must be exaggerated to an “on par” equivalence with European settlers, so that rationalization for a return to the romanticized “ideal” conditions can be made.

“Exaggerating the development of pre-contact indigenous societies prevents the recognition that a revitalization of Indigenous traditions…would mean…relatively unproductive, small, and simply organized entities today. This would act to maintain Indigenous groups in a state of perpetual dependency…” -FW

Perpetual dependency is exactly what is needed to keep the Aboriginal Industry alive. Because it “cannot ensure self-sufficiency,” the infrastructure required to maintain “separate economic, political and education systems,” ends up maintaining “the dependency that justifies the demand for more transfers.”

The Final Report largely ignores analysis that considers “the imperatives of European states that led them to make the voyages that resulted in contact,” and the fact that “one would expect…these imperatives would play a significant role in the interaction, which must be understood in any future policy proposals.”

The decision to largely ignore “the imperatives of European states” is at the heart of the Royal Commissions operating assumptions. Clearly the forces of global capitalism that both settler and Indigenous populations were integrated with, albeit unevenly, contained the most powerful casual forces of change and development, but the Royal Commission has an entirely different way of conceiving the situation, which has little use for “inconvenient” historical and material facts.

The “interaction” (between settler and Indigenous populations) Widdowson refers to, is highly uneven. However, the Royal Commission’s adoption of parallelism precludes it from analysis that employs the political economy framework “uneven and combined development”; a lens perhaps best suited to shed light on Canadian Indigenous-non-Indigenous relations from the origins to present day.

The Royal Commission’s ideological assertion that the state of unevenness between Indigenous and non-indigenous is due to the attitudes of settlers, not developmental pressures relating to the political and economic imperatives of global capitalism, leads them to believe that a change in the attitudes of non-Indigenous, along with a revitalization in Indigenous ancestral practices, is what is required to break the cycle of dependence.

Postmodern thinking is obsessed with identities. It is “essential” that the various identity groups hold the correct, culturally sensitive and relativistic attitudes regarding one another. This emphasis results in a false conception that identity politics drives change. However, the pressures of global capitalism, the corresponding regimes of accumulation and their behaviour-molding modes of regulation, imposed unevenly on and between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities, are the pre-eminent factors influencing change. This is wilfully ignored because relativistic postmodern notions found in postcolonial theory and parallelism offer a more lucrative pathway for the corrupt rent-seeking Aboriginal Industry to prolong dependency and justify endless government transfers required to meet their culturalist aspirations and corrupt business model. Although, as will be discussed in the next section, the imperatives of global capitalism are not the only disruptive forces of change ignored by the Royal Commission’s acceptance of a postmodern understanding of Indigenous issues.

Post Fordist-Flexible Accumulation and Postmodernism are Products of the same Destabilizing Discontent Driven in part by Disruptive Communications Media

Canadian political economist Harold Innis, known for his study of Canada’s fur trade and the development of the staples thesis, said it was the balance between oral and written forms of communication media that allowed Greek culture to thrive. Prior to the industrial revolution, and continuing through the first half of the 20th century, the industrializing world was dominated by visual/pictorial forms of media; a condition well-removed from the balance of the Greeks, but one ripe for an organizing system like Fordism. From the second half of the 20th century stretching up to the present, with first, the appearance of electronic, and later, digital media, and coupled with a predisposition for the visual, our attention relentlessly directs to continuous ephemeral forms (ie. social media) which emphasize a present-mindedness, resulting in a lack of attention, and therefore loss, of the permanence of cultural symbols important for an overall sense of societal purpose and cohesion.

It was during the Fordist period when Innis wrote the words quoted below. A disruptive electronic communications medium, the telegraph, was bringing about the conditions he describes. This electronic device allowed newspaper producers to offer continuity, through ongoing updates of a shared public narrative, essentially overcoming the time and space limitations of news collecting and reporting. However, the unbalancing of society, by way of over-emphasis on the visual and ephemeral, sees its origins in the creation of the mechanical printing press that made possible the mass dissemination of print (which soon became the dominant medium) and the industrial revolution.

“The overwhelming pressure of mechanization evident in the newspaper and the magazine, has led to the creation of vast monopolies of communication. Their entrenched positions involve a continuous, systematic, ruthless destruction of elements of permanence essential to cultural activity.” Harold Innis (Changing Concepts of Time)

Postmodernism by nature does not seem to create anything of permanence; instead, it deconstructs the products of permanence by attacking the systems that continue to generate the body of post-enlightenment knowledge associated with modernity. Whereas knowledge produced of modernity is usually built on principle-based foundations evolved through western post-enlightenment academic traditions, postmodernism favours and imbues a flexibility of process (or no process at all), over structured or formal methodologies.

At the same time that Western political economies were transitioning to flexible regimes of accumulation, along with the corresponding shifts in modes of regulation of the labour class, the conditions for “flexible thinking” taken to the extreme, postmodernism, were set. This, combined with the onset of permanence-destroying, time and space dissolving communications media, accelerated the “psychic shift” of the postmodern turn.

As cool as certain aspects of postmodernism can be - take for example painting, film and architecture - it is a destabilizing assault to permanence and tradition to be confronted with ideas and images that do not know why they exist, other than to challenge tradition and elude permanence.

Modernity culminated into exhaustion when its principles were pushed to extremes; past the limits of their potential thereby reversing their characteristics as Marshall McLuhan would say. It was primarily the forces of industrial capitalism and the inherent requirement for cost-cutting and profit-maximizing that drove Fordism, Taylorism, Managerialism, and the general instrumentalizing of people to the point of exasperation. The response, or McLuhan-ian reversal, was acceptance of postmodernism in academia, art and culture; and a transition to post-Fordist flexible accumulation, and the associated collection of human behaviours (modes of regulation) in the political economy.

It is clear that the framework of uneven and combined development, even though ignored by the Royal Commission, fits the situation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous in Canada. This framework recognizes the changes in the conditions and levels of unevenness according to the historical periods of concern. Just as important, in my view, is to recognize the general uneven conditions brought about by communications media and other noteworthy technological disruptions indicative of these historical periods.

These modes of analysis ask: what are the pressures associated with political economy, and what are the effects on people and society? What are the pressures (and Innisian bias) associated with communications media, and what are the effects on people and society?

Where the analytical frameworks of political economy use historical, material, economic and political facts and evidence to better understand the inter-relations of geography, trade & commerce, religious & cultural practices, education, public policy, etc., analysis of the effects of communications media and technology can explain much about the general attitudes and dispositions of people, and even more about key societal transformations.

For example it is the presence of communications media in remote reserves that give Indigenous children a window into the high-tech industrialized world; This presence brings about a condition where Indigenous children become interested in the exciting modern world delivered ephemerally and continuously, as well as visually/pictorially, through addictive digital devices. Traditional practices don’t stand a chance against these natural forces of change and development; only a well funded Aboriginal industry can pretend otherwise. The result being that Indigenous children will be misled, while better opportunities beyond either their physical location or education level, will continue to be unavailable.

“Subsistence economies function at the lowest historical levels of productivity. To advocate for a return to them is beyond reasonable consideration, and denies aboriginal youth access to, and participation in, the modern world.”-FW

In the example used above it can be argued that keeping Indigenous people isolated in difficult to access areas, for the purpose of revitalizing traditional Indigenous economies and practices, ignores both the realities of political economy and an analysis of the conditions and effects brought about by communications media. “Flexible thinking,” and its tendency to adopt postmodern assumptions, leads people to confusion. Postmodern identity politics holds that cultural identities are sacred, and their preservation is of prime importance; not, for example, the success, health and happiness of Indigenous people. Not concerned with the cost and consequences, it is the preservation of Indigenous ancestral identity regardless of the unsustainable and incommensurate situation that arises, that creates the conditions for the Aboriginal Industry to thrive.

Postmodernists may claim that postmodernism itself is a framework of analysis; except there are no guiding principles like in other theoretical/analytical frameworks. Instead, what occurs most often in practice is the holding and repeating of ideological assumptions, rather than the employing of a mode of analysis that provides anything useful or concrete.

Another way to look at the effects of media is through the lens of dependency. Although in this case, I’m using the McLuhan-ian definition of media: extensions of man, any hardware or software human invention (ie. Marxism, lawnmowers, books, tooth-picks, podcasts, Buddhism, iPhones - are all considered media).

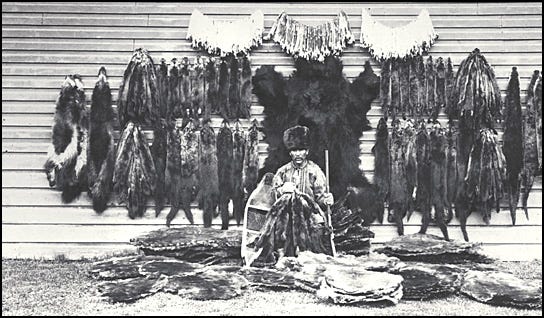

During the era of the Canadian fur trade, Europeans settling in Canada were dependent on the Indigenous - for their traditional knowledge (ie. knowledge of where and how to trap the beavers) and “media” or technologies (ie. the snowshoes required to transport beaver pelts). These early settlers, due to their staples-based economy, not yet capable of producing the surplus required for an advanced civilization, were also heavily dependent on the far richer European countries sponsoring the colonization projects in the new world.

The Indigenous, in turn became dependent on the settlers for steel traps (and other tools manufactured in Europe), traded for the furs they procured. European settlers organized their new societies around European modes of political economy, and over many years built an agriculturally based means of surplus production, then transitioned to an industrial one. During this time, the fur, and other stapes based industries, declined and dependency became more and more uneven. As the Indigenous were not disciplined into the modes of regulation required to facilitate inclusion in the industrialized global economy Canada was seeking to integrate with, the settler population chose to import from Europe the labour force necessary to meet these economic imperatives.

In so doing the settler population broke free of its dependence on both the Indigenous (as a consequence of the decline in fur and other subsistence trades) and their old world patrons (as a consequence of acquiring the means to generate surplus through agriculture and industrialization).

Postcolonial theory & Traditional Knowledge

“Rather than examining political institutions, cultural features and ideologies in abstraction, political economy attempts to explain these phenomena by indicating how they have historically emerged in association with the development of productive and distributive practices. In opposition to idealistic theories that perceive history as the outcome of a “clash of wills” that arise spontaneously and inexplicably, political economy asks how human ideas and actions are ultimately socially determined by the “production and reproduction of real life”. - Frances Widdowson

The source of the “ideologies in abstraction” and “idealistic theories” being postmodern postcolonial theory. To be more specific; the internal colonial model. This model sees dependent bands of Indigenous peoples as “colonized” nations within the Canadian state. Elite bodies like the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples operate unapologetically within the assumptive ideological framework of these theories.

“Postcolonial theory’s postmodern concern with incorporating ‘Native ways of being’ and the ‘differing perceptions’ of aboriginal peoples has led Canadian political economy to move away from analyzing aboriginal peoples in the context of ‘the actions of capitalism and the state.’” - FW

Where material methods seek to understand the truth, ideological notions function a priori. The opposite of a material approach is an ideological one. In Canada, the ideological assumptions of the internal colonial model are widely accepted.

“...much of the attempt to understand aboriginal economic and political circumstances has been left to postcolonial theory, and a focus on hypothetical transcendental cultural factors rather than historical and material ones.” FW

Assimilation and the Destruction of Cultures

“... it is cultural survival, not economic viability, which is the focus.” -FW

Assimilation, and the destruction of cultures, is a natural part of life. This explains how France, for example, ended up with French as the official language. Innis’ “destruction of permanence” brought about by forces of change and development causes disruption. The imperatives of survival for all swept up in the maelstrom of events, pressures, distractions, and confusions, involve facing difficult truths about reality. This cannot be achieved under conditions of postmodern idolatry. This “false-god” cleverly conceals himself among common things; everyday words and expressions. Learning how to identify and decode this postmodern “demon” is a skill worth acquiring.

The identity politics of cultural relativism creates a situation where minority cultures are favoured and great concern is given to the “destruction” associated with their practices and ways of life. The concern for the “destruction” of symbols of permanence important to the majority populations is not shared, in fact, they are often actively attacked. However, we can and should be just as concerned with the destruction of the majority culture as we are with the destruction of minority cultures. Or, just as equally aware that both are collapsing into each other.

Conclusion

Because of the uneven and combined developmental course involving Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians, the transitory shifts discussed in this essay have had differing effects on the two groups. However, nothing about any of this subject matter can be understood through esoteric forms of postmodern rationale. Emphasis on the material and historical of political economy, and of the observable effects of communications media, a la Harold Innis, should be viewed as the primary sense-making methods with anti-reason postmodernism relegated to an esoteric alternative.

_____________________

For more on this topic, by this author, try - The Corruption Of Canada’s Indigenous Victim Industry: How Rent Seeking Profiteers Benefit From The Postmodern Turn And Contribute To Indigenous Dependency

Profound analysis. Traditional knowledge and culture of groups unable to support themselves should not be Canada’s concern. Rather than postmodernism theory and traditional lifestyle, the indigenous need to fit into modern society and assume the same responsibilities and rights as others.