Re-Evaluating Canada’s (Un)Truth and Reconciliation Commission

How The Public Forum Leads To Entrenchment of Postmodern Myth

“Victimism uses the ideology of concern for victims to gain political or economic or spiritual power.” ― René Girard

Introduction

Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission has received little criticism. This extends to the assumptions on which its necessity was rationalized, its structure, its stated objectives, the execution of its mandate, and in the aftermath, how it has altered Canadians' sense of national identity, and how it has contributed to the shared desire for reconciliation.

The totalitarian condition of reified postmodern identity politics (wokeism) is responsible for the lack of criticism and unwillingness of Canadians to speak their minds, or ask difficult questions (out of fear of causing unintended offense). This postmodern situation also requires that the concept of truth be subjectivized, and that for the purposes of healing and reconciliation, claims made against the architects of residential schools (the Canadian Church & State) must be accepted as the truth.

The first, and most glaringly obvious problem with Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation process, is that what is meant by “truth,” is not the generally held conception of the majority of Canadians. The TRC rejects universal truth and uncritically accepts unsubstantiated subjective testimony, as absolute and unquestionable. This also comes with an expectation that Canadian’s, and the rest of the world, accept the TRCs revision of the story of Canada. However, historical truth is not arrived at by eyewitness accounts alone; material and corroborating evidence is compiled, and as new discoveries are made, historical representations come into focus and reveal previously unseen layers of nuance.

The postmodern composition of the TRC took the culturally relativist position that the Indigenous conception of history must also be accepted as truth. More on that later, but for now you should be getting the impression that the Truth and Reconciliation Commission failed miserably on the “truth” part of their project. Getting to the actual truth doesn’t serve the needs of the Aboriginal Industry, so they used an alternate conception more in line with the actual agenda.

“Acceptance of the aboriginal view of history, according to the Royal Commission, was a way of entering into reconciliation and renewal with aboriginal peoples.” -FW

This essay discusses some of the arguments found among a growing number of journalists and academics whose views represent a departure from the prevailing narratives on Indigenous issues in Canada. Often the source of trouble for the people who hold them, like in the case of Frances Widdowson, it is my contention that all viewpoints should be considered; including uncomfortable and inconvenient ones.

On that note, allow me to begin my essay in the way that one of my sources, Tom Flanagan, ended his:

“None of this is to suggest that the people who reside in First Nations communities do not have many legitimate grievances, or that many people were not harmed in residential schools. The concerns are real, the harm is real, and both must be addressed. However, believing stories that are not true does none of that.” -TF

Correcting the Record

It cannot be stated enough that it is not a “denial of historical wrongs” to challenge, examine, or critique the claims of some of Canada’s Indigenous peoples, or what Frances Widdowson and Albert Howard call the “Aboriginal Industry,” or the prevailing narrative on Indigenous issues still taking shape in the wake of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Dispassionate search for truth in response to stories and claims that are not believable, however forceful some demand acceptance, in my opinion, is appropriate and necessary.

The work is already being done in various ways by academics, researchers and investigative journalists. This essay aims to bring together some of their findings and arguments with the goal of convincing readers that Canadian Indigenous issues are far too complex to be reduced to a victim/perpetrator dichotomy - where institutions are made into villainous quasi “personhoods,” and atrocities of the most depraved nature, committed against children, are openly participated in by groups of nuns, priests and oblates.

“Although not a single police report, newspaper account, or any other historical record supports these allegations of murder and secret burials, distinguished indigenous leaders, including TRC Commissioners Murray Sinclair, Wilton Littlechild, and Marie Wilson, as well as former Kamloops chief Manny Jules and Dr. Ron Ignace, appear to believe tales of six-year-olds secretly burying bodies late at night. Meanwhile politicians and journalists hold their tongues, and offer no pushback against stories that are clearly fictional.” -TF

As unpopular as it may be to question the claims of former residential school students, regardless of the degree of plausibility, it is even more unpopular to ask about positive aspects of the schools. Or, to ask if the Indigenous would have been better off without a westernized education (which included learning to speak, read and write in English). We are to believe uncritically that absolutely everything about residential schools was an abysmal failure responsible for intergenerational harm and cultural genocide. These are serious charges to accept uncritically, especially considering the large amount of material evidence and eyewitness accounts that seem to contradict this victim/perpetrator narrative.

On the other hand, there is an astonishing lack of material evidence to back up claims of former residential school students. For example, there are no records of any Indigenous children being murdered at a residential school, nor are there records of parents reporting their children missing from a residential school. There are thousands of claims of murdered residential school students, but no documentation from police that any of these “cases” were ever reported by parents. Are we to believe that all of the affected Indigenous families held their tongues all those years in silent indignation in spite of the gross injustice which they were subject to?

Things changes in the 1990s when Chief Phil Fontaine, in a nationally televised interview with Barbara Frum, confessed that he had been abused as a child in a residential school. Turning points like these, are the sites of activity where we can make connections regarding the reality of Indigenous affairs and the typical unrealistic conceptions of them. The effect of this widely viewed interview, seemed to galvanize support and catalyze a new era where widespread perception of Indigenous Peoples as oppressed sufferers of intergenerational trauma began to take hold.

In an article in the American Conservative, Frances Widdowson, compares the “Satanic Cult” moral panic of the 1980s/1990s (the same era as Chief Fontaine’s pivotal interview) - where over 12,000 unsubstantiated accusations of abuse were made - to the moral panic that erupted after the discovery three decades later of soil disturbances near the site of a former residential school in Kamloops, BC. Soil disturbances that may (or may not) be graves of people, who may (or may not) be children, who may (or may not) have died of murderous causes.

Widdowson discusses the “Satanic Panic” documented in the book Michelle Remembers published in 1980:

“The case involved Michelle Smith, who, after engaging in recovered memory therapy, made sweeping claims about the satanic ritual abuse that she claimed to have endured. The book presented itself as being factual, but scrutiny of its contents did not corroborate its claims. This did not prevent it from instigating a social contagion, leading to a satanic abuse moral panic in the 1980s… made possible by the implantation of false memories. Research in psychology has shown that it is easy to manufacture memories, especially in people who are emotionally disturbed.” -FW

It is interesting to note that similar to former residential school students, the people who made claims of satanic abuse were also commonly identified as “survivors.”

Laundry List of the Wrong Kind Of Evidence

“It was only after the Fontaine interview that stories of residential school atrocities gained ground, even though they were contradicted by the explicit evidence of some contemporary indigenous leaders.”-TF

For example,

“We all heard of horrible lies created by some individuals in order to receive as much money as they could.” - Former Dene Chief Cece Hodgson-McCauley

As Hymie Rubenstein has pointed out, there is “not a single known victim, not a single identified murderer, not a single grieving parent looking for a child who went missing while attending a residential school, and not a single body.”

In his autobiography, Breaking Trail, Senator Len Marchand, has good things to say about his experience at Kamloops Indian Residential School: “The reader might expect me to tell a few horror stories about physical and sexual abuse at the residential school. But I know of no instances at KIRS. There was the strap for serious transgressions, to be sure, but that was no different from the corporal punishment that was doled out to white students in the better schools of Vancouver and Victoria. I was never abused, and I never heard of anyone else who was mistreated at the Kamloops school. The nuns and priests and brothers had some old fashioned notions about what Indians were and what we needed, notions that today young Indians would find at best quaint, and at worst, offensive. But they meant well by us, and they all did their duty by us as they saw fit.”

In the 1990s, even in the years after the Chief Fontaine interview, viewpoints like the following were common, and no trigger warning was necessary: “Chief Clarence Jules, a respected three-term chief of the Kamloops band, also attended Kamloops Indian Residential School. In ‘Our Chiefs And Elders’, published in 1992, he complained that he had been strapped for speaking his own language at the school, but thought it was ‘probably the best system we had around at that time.’ He said nothing about murder and mayhem, nothing about secret burials or any of the other fantastic claims now being made.”-TF

Ground penetrating radar may have found soil disturbances, but excavations have yet to discover any actual graves or human remains - “The list of former residential schools and Indian hospitals where excavation has yielded nothing and stories of burials have been proved untrue includes the former Mohawk Institute at Brantford, the former Shubenacadie Indian Residential School in Nova Scotia, the Charles Camsell Hospital in Edmonton, and the Kuper Island Indian Residential School in British Columbia.” -TF

Tomson Highway (who attended a residential school for nine years) from an interview in the Huffington Post, published in 2015 shortly after the release of the TRC’s report: "All we hear is the negative stuff, nobody's interested in the positive, the joy in that school. Nine of the happiest years of my life I spent it at that school. I learned your language, for God's sake. Have you learned my language? No, so who's the privileged one and who is underprivileged? You may have heard stories from 7,000 witnesses in the process that were negative, but what you haven't heard are the 7,000 reports that were positive stories. There are many very successful people today that went to those schools and have brilliant careers and are very functional people, very happy people like myself. I have a thriving international career, and it wouldn't have happened without that school.”

Later in the same article, Tomson adds: "[But] only we can solve the problem and the only way we can do it is to go to school, get a fantastic education, and just do successful things. We need young native people to grow up believing that they can be brilliant and successful. That's the only way we can fix things: elevate the level of education, elevate the level of literacy, and it will elevate the frequency of success."

Robert Niezen’s book, “Truth & Indignation: Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission on Indian Residential Schools,” includes a number of interesting findings which lend strength to the position that the history of Canada’s residential schools is more complex and nuanced than many who are caught up in the swell of emotional hysteria are willing to admit.

There are numerous accounts of members of the Oblate order, assigned to Canadian residential schools, who learned various Indigenous languages. When Niezen visited a residence of the Oblates to conduct interviews regarding the TRC, he was shown several volumes of Indigenous language dictionaries that the Oblate brothers had created. Some painstakingly handwritten and leather bound. This seems more like acts of cultural curiosity and preservation on behalf of the Oblates, and does not square with claims of “cultural genocide,” or that Indigenous students were not permitted to speak their language.

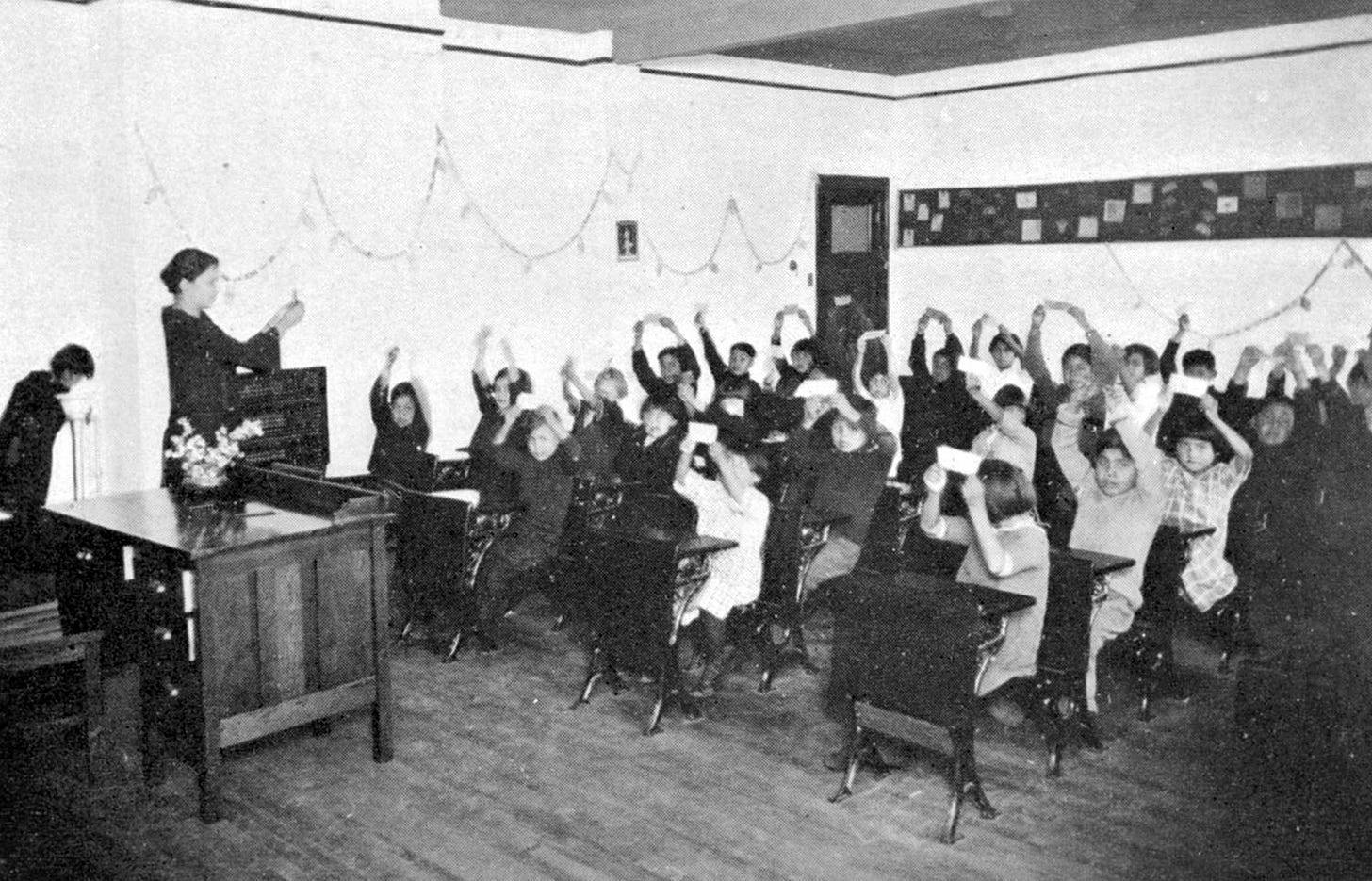

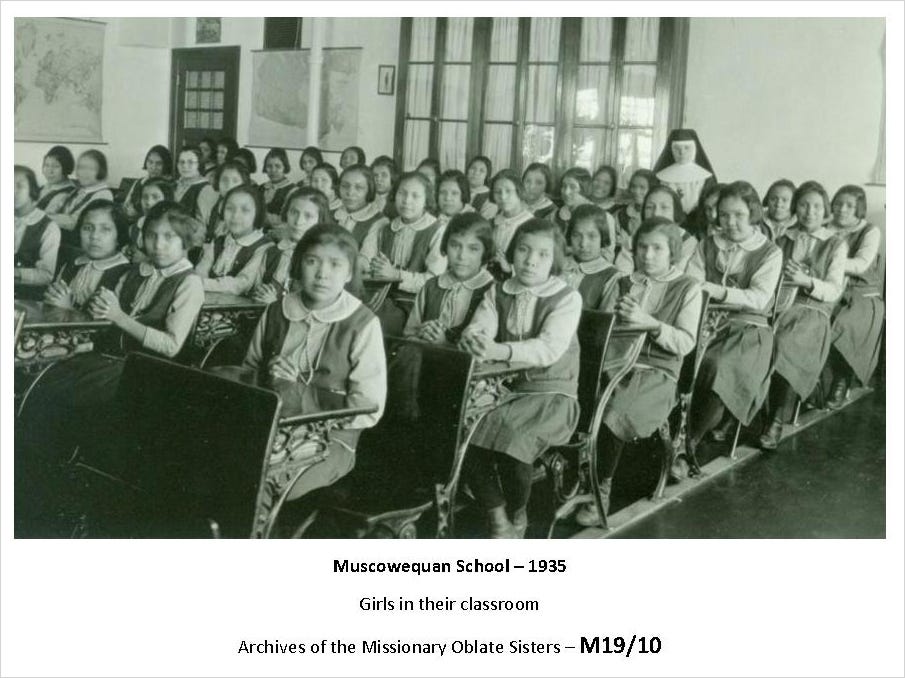

In another section Niezen describes the participation in TRC events by nuns who had served formerly at residential schools. They were usually stationed in adjacent space removed from main event attractions (the area designated for audiences to hear graphic witness testimony). Although not visited very often, the nuns had displays of photographs illustrating life at the residential school they were part of. These photographs, representing their “truth” and lived experience, documented tableaus of smiling students crafting traditional beadwork, practicing archery, fishing and playing hockey; however, this was not the perspective that the majority of those attending TRC events were looking for.

The care and effort the Oblates demonstrated in preserving Indigenous languages, and the nuns' photographs contradicting claims students were prevented from engaging in their cultural practices, make accusations of cultural genocide seem absurd. For those able to remain dispassionate in pursuing the truth of Canada’s historical relationship with the Indigenous, a pattern of contradiction tied to the invocation of the victim/perpetrator dichotomy and other simplistic assumptions of postmodern postcolonial theory is not hard to see.

Made-up stories of horrid abuse, and the prevalence of exaggerated depravity in residential schools, has led to a kind of personification of the Cdn government. A stigma, generally associating the Canadian “person”/state with “evil perpetrator,” seems to have taken hold of public consciousness. The same can be said, although to a much worse degree, about Christianity, directed mostly at the Catholic Church. The diffusion of the perpetrator identity arrives at its final destination once combined into the collective impression of Canada’s non-Indigenous, aka “the settler population.”

The postmodern turn has brought us to a place where complex issues are reduced to binaries. The victim/perpetrator dichotomy, while introduced in an earlier period, has firmly taken root in the wake of Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and the subsequent discovery of “unmarked graves” on the grounds of former Indian Residential Schools.

The widely held belief that the Canadian government and Catholic church perpetrated systemic murder and abuse, of the most depraved forms, against the Indigenous, creates a condition where having national pride is now somehow proof of ones complicity in the “ongoing cultural genocide” of the Indigenous. Tom Flanagan points out - “the country can only expect bad things to happen from people who are convinced that they are the permanent victims of an evil system.” Taking Flanagan’s thinking to the next step, we should also consider the likelihood that “bad things” will happen due to non-Indigenous peoples shared impression of themselves as ancestrally derived from a shameful, murderous, and oppressive ethno-national family.

Culturalism, Parallelism, Cultural Genocide, and Reified Survivor Identity

According to the pragmatic Frances Widdowson - “the use of the term ‘genocide’ in connection with culture is a rhetorical strategy designed to impede rational discussion of the residential schools. This is because it turns inevitable and unstoppable socialization and educational processes into a crime against humanity.”

As Widdowson explains in her essay, The Political Economy of Truth and Reconciliation, the pressures of settler colonialism, specifically the necessity to evolve beyond a staples based economy in order to support a growing population, drove the need for residential schools.

“Notions of ‘cultural genocide’, in fact, are completely at odds with the historical and material assumptions of political economy, which asserts that ‘what we do’ is determined by our relationship to production, which, in turn, is influenced by productive forces. The culturalist assumptions of parallelism, however, deny the evidence that exists showing that cultures evolve.”-FW

Widdowson argues the reason residential schools were created had everything to do with the imperatives of capitalism. The decline of the fur trade made urgent the need to educate and socialize the Indigenous population into habits and practices consistent with the shifting economy. Although it is recognized that the course undertaken by the government resulted in many unforeseen harms later understood to be the cause of much suffering for the Indigenous community, it is the postmodern assumptions found in postcolonial theory, the victim/perpetrator dichotomy, and the ideology of parallelism that permits confusion, historical revision, and denial of the notion that harm caused by residential schools could not have been fully understood or appreciated at the time of their creation.

“A certain amount of “cultural loss” was inevitable if aboriginal people were to survive in the modern context.” -FW

The concept of culturalism, developed by New Zealand political economist Elizabeth Rata, applies to the situation with Canada’s Indigenous. It is a postmodern relativist idea where cultural characteristics of Indigenous groups are not considered to have derived from local knowledge, but birthrights inexorably tied to ancestry. This essentially freezes the Indigenous in time by abstraction from the natural occurring processes whereby peoples improve their technologies and progress through developmental stages on their way to advanced civilization. Because culturalism denies development, and inherently sets in stone Indigenous identity, any notion of their assimilation into the dominant culture gets equated with cultural genocide. When realism and pragmatism are absent, what is often found in their place is identity-obsessed postmodern ideology.

“This deference to the aboriginal ‘conception of history’, first given legitimacy by the Royal Commission, increased acceptance of the view of aboriginal organizations that the residential schools were a form of ‘cultural genocide’...As Lysanne Gagnon points out, if the term ‘cultural genocide’ was used the same way in other contexts, every single nation on earth would be guilty of this process.” -FW

The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples final report included the first appearance of parallelism, an ideology that makes relativist assertions that conceives Canada’s Indigenous as existing with separate cultures in separate nations. This is consistent with culturalism, demonstrated by the acceptance of traditional knowledge as systems separate from those of non-indigenous knowledge, and Indigenous conceptions of history as separate from those of non-Indigenous history. Essentially, a universal history, or objective truth, is not part of parallelist conditions.

This leads to the ramification of demands for Indigenous history and ways of knowing to be accepted, new forms of victim oriented identity be reified (ie. the residential school survivor) and subjective truth be believed. In other words, the installation of a postmodern operating system on the CPU of Canadian culture.

“As a result of the acceptance of this parallelist ideology, in a few decades the residential schools went from being viewed as ‘a necessity for providing language skills (English), job training, personal discipline, piety…and security in a changing world’ to being designated as ‘a source of trauma for individuals, families, and communities’.”-FW

The Hidden Motives and Emergent Qualities of the TRC

“With respect to indigenous leaders, this can be explained by what I have called “neotribal rentierism,” where compensation is extracted for wrongs that have been committed in the past. This rent-seeking has been assisted by “woke” non-indigenous academics who assume that, to combat oppression, they must ‘shut up and listen’ and unquestionably accept the indigenous ‘genocide survivor’ identity.” -FW

In The Political Economy of Truth and Reconciliation, Frances Widdowson details the monetary incentives and corresponding rent seeking processes of what she calls neotribal rentierism, to explain the motives of organizations like the TRC. But beyond financial corruption, another explanation for much of the energy and public support of the TRC, and the resulting widespread acceptance of a new Canadian historical narrative (tied up in national perpetrator identity), can be found in Ronald Niezen’s ethnographic inquiry into the TRC.

“The socially formative responses to controversy, it seems to me, are in some ways more significant than the causes themselves. The collective sense of indignation has a different, broader meaning than the particular causes that provoke it.” - RN

Maybe the emotional, especially the indignation-inducing, aspects of the TRC’s public “truth telling,” and of the adjacent genocide narrative twisted within, serve at least partially, a hidden manipulation few can identify, let alone resist? Maybe the TRC is essential for the obfuscation of the Aboriginal Industry and its associated neotribal rentierism? It has been observed that postmodern identitarians justify their actions and ideas on recontextualized kernels of truth they strategically exploit. But twisting the truth out of context is just fancy lying, which of course, they are the forever world champions of.

None of this is denying the individual truths of those who suffered harm and trauma. Instead it is recognizing, like many things organized by humans, there is a degree of collective dishonesty; and in this case, behind-the-scenes corruption. The real objective truth concerning residential schools can only be discovered through honest investigation putting aside all postmodern assumptions and culturalist sensitivities. However, it is the totalitarian conditions brought about by these postmodern assumptions, emotional manipulations, and resultant widespread guilt and indignation felt by Canadians, that explains our general inability and unwillingness to examine critically these difficult issues.

Filling people with lurid details of awful stories of abuse suffered by former residential school students, whether plausible or not, inspires indignation consistent with the TRC’s purpose. Another less obvious reason, might be to distract from the large amounts of monetary settlements transferred to residential school “survivors” in the wake of TRC awareness-raising public relations campaigns and the legal processes designed to extract this compensation.

Acquiescence to claims that are untrue justifies profligate government spending, tarnishes the national reputation, lays the groundwork for more claims of opportunistic rent seekers, and leaves the general public in a state of shame (robbing the citizenry of any spirit they may have to, for example, celebrate the yearly anniversary, Canada Day). All of this raises the question of exactly how the TRC’s efforts will lead to reconciliation between Canada’s Indigenous and non-Indigenous? What is described above should be enough to convince Canadians to demand proper investigation into claims of historical wrongdoing. But in the current postmodern climate, it's not likely to happen.

The Structure of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission

“Although it is not always on the surface, there was arguably more disputed, mutually contradictory meaning-making in Canada’s TRC than in any truth commission elsewhere…The Commission…will have succeeded if it convinces a sufficiently large number of citizens of the harm done by the schools…and it will have failed if too many remain unpersuaded…” -RN

Critics of the TRC, like Frances Widdowson, have argued that - “It is clear, in fact, that the TRC overrepresented testimonies from those who found the residential schools to be genocidal.”

It should be of concern to all Canadians that our Truth and Reconciliation Commission had a public relations mission aimed at convincing the nation to accept a victim/perpetrator dichotomy and the characterization of residential schools as culturally genocidal; based almost exclusively on unsubstantiated witness accounts. And of course, regardless of the prevalence of contradictory witness accounts and material evidence.

In Canada’s TRC events, “survivors” providing testimony were permitted to say whatever they liked regardless of the plausibility of their claims. In a short time, a “public” (as Niezen frames it), formed and expectations of the content of witness testimony emerged. The most gruesome, depraved and heart wrenching confessions were rewarded with the strongest audience reactions. These moments created emotional associations with the emerging narrative, fostered a strong sense of community amongst many who were previously unknown to each other, and instilled a strong sense of identity rooted in victimhood; which seems to have been the purpose of the whole spectacle.

“The motivation of the TRC was to rewrite history, whether they saw it that way or not.”-RN

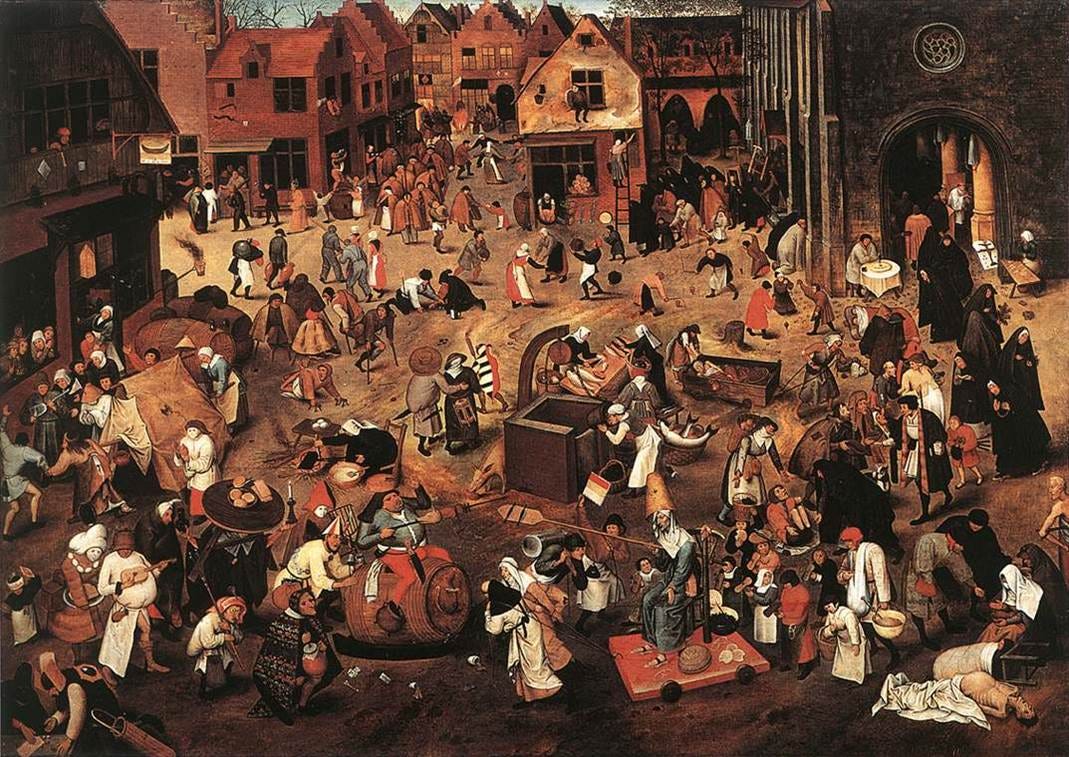

The TRC was set up under a victim-centered framework. A newer model of transitional justice also utilized in the Truth Commission related to South Africa's Apartheid regime. The more common perpetrator-centered model focuses less on survivor testimony and more on the things needed to bring perpetrators to justice. Matt James, Associate Professor, Department of Political Science, University of Victoria, has written that Canada’s “victim-centeredness is more than a matter of dignity and respect. It is also a matter of transformative potential.” In the paper quoted below he discusses how a victim-centred approach intersects with the carnivalesque.

“The idea of the carnivalesque…evokes the transgressive potential of medieval festivals, with their anti-authoritarianism, reversal of hierarchy and suspension of routine…to highlight the dramatic reversal of dominant assumptions and routines that victim-centred approaches typically entail.”-MJ

This break from convention, or disconfirmation of familiar forms, is at the heart of postmodernism. Notice the postmodern relativist assumptions in the following reference to “diverse truths,”

“Just as the medieval carnival was a ‘world upside down,’ where the popular and polyphonic trumped the monologic and official, so the carnivalesque truth commission rejects the sterile legalism of the bureaucratic state and its fora. It puts victims of injustice in charge and makes room for diverse truths and diverse forms of truth telling.” -MJ

New Media, Public Justice, and Identity

“Several studies have noted the significant place of public persuasion in human rights reporting and activism, oriented toward an amorphous public sphere often referred to simply as the international community.” -RN

Ronald Niezen’s ethnographic approach to the TRC included the “influence of abstract, impersonal, largely unknowable and unpredictable ‘publics’,” an area he calls - “an entity that has been neglected by ethnographers.” It was “clear that the TRC was directed toward, and in some ways responsive to, the public(s),” through the TRCs use of new media. Specifically, the live streaming to the internet of the “survivor’s” stories, but also “there was a long-term orientation to the use of media…that included the goal of a permanent research centre with a digital archive of survivor narratives.”

“Engagement with public audiences, in a sense the ‘consumers’ of justice claims, has important implications for the...processes by which distinct people define who they are - above all the ways they articulate and defend their collective rights…are now more than ever before negotiated and ‘mediated’ (literally and figuratively) in collaboration with mostly unknowable, abstract masses of people whose preferences and inclinations are formed and manifested through media.” -RN

Niezen discusses how the TRC is responsible for the creation of a new kind of person; the residential school “survivor,” who emerges through a sort of selection bias of stories of TRC participants. Through various processes, involving predominantly the use of new media - “the Commission encouraged particular, prefered narratives through examples provided to potential statement givers and audience members that ‘set the tone’ for the experience of the bearing witness.”

In one example of testimony Niezen writes about, representing a departure from the norm, a Catholic Priest expresses a contradictory view. He asserts that his story is his truth and he sees residential schools in a more positive light than the emergent narrative. The live audience reacted with hostility, disincentivizing anyone else who may have had an alternate viewpoint to contribute.

All of this pressures one to “perform” the role of survivor in a way that is consistent with the emerging public's expectations.

“...if publics were to be given the attributes of human personality, they would be…suffering from something akin to bipolar disorder, compounded by narcissism, immaturity, and passive-aggression…the ideas they respond to and express…are inconsistent, sometimes even starkly contradictory, to an extent that we would not find in a normal adult individual.”-RN

Unfortunately, because of pressures to believe and respect the subjectivity of indignant publics who make unrealistic and disproportionate demands for social justice, we seem to be stumbling through this woke era with no indication of when or how we will regain our footing.

_____________

Thanks for reading. For more from this author on the topic read:

An outstanding piece that needs to be rewritten for publication in a better known journal so as to reach a wider audience.

Readers who enjoyed it might want to visit my site devoted entirely to the Indian Residential Schools called “The REAL Indian Residential Schools Newsletter” at: https://hymie.Substack.com.

Governments which spread lies are not only in the past and in some distant land but right here in Canada. The narrative on IRS abuse is largely a canard so various people and groups can milk the system. James’ article is excellent in every way and merits broad dissemination.