Woke Watch Canada is a reader-supported publication. Please consider becoming a paying subscriber or making a one-time or recurring donation to show your support.

By Karli Lewis

I instantly recalled that saying, “you don’t choose books, they choose you.” when I caught a glimpse of Rita Joe’s, Songs of Rita Joe: Autobiography of a Mi’Kmak Poet, sitting there on the dresser at mom’s. In the same bedroom I’d seen it in 15 years earlier, the very first time I’d come to Eskasoni as a young teenager.

Never once in all those years had I felt a yearning to pick it up until that day, 2 summers ago.

It was one of those moments where you couldn’t help but realize the divine purpose in God’s timing.

Written in 1996, I knew I could depend on this book to be free from the influence of today’s radical woke cultural narrative; before all the “truth and reconciliation” nonsense began. I prayed a quick prayer, asking God to provide the answers I sought, and committing to accepting whatever those answers may be.

In her book, Rita describes a painfully hard life on the reserves she lived in. Her father was “in his 50’s or 60’s” when he married her 16 year old mother. Like most others on the reserve, her family lived in poverty. She recalled going house to house as a child so she could find food to eat when she got hungry. Her mother died when she was 5 but one memory that stuck out to her was her mother snapping gum in church. (This confirmed another aspect of life on reserve that many seem to forget or intentionally omit from the current narrative: that many native people had already been going to church before they ever went to a residential school.)

After her mothers death, she, her father, sister and oldest brother went to live with her grandmother, who she describes as a “cross old lady”, who often yelled at her father, and for reasons unknown, blamed her for her mother’s death. She had two other brothers who were away at the Shubenacadie IRS.

She says that her father depended too much on her sister, who was 10 years old, to look after Rita and do all cooking, washing, sewing and other chores.

She doesn’t clarify how long they stayed there, but it doesn’t sound long.

After that, she leaves with her father and sister while her oldest brother stays with her grandmother. She goes into a succession of foster homes, staying at each one anywhere from 2 weeks to a year, in nearby Mi’kmaq communities, with people familiar to her father.

The first one is in Membertou, where she goes to live with her older half sister Susie Marshall, who was married. She recalls Susie’s husband being “mean”, saying “when he hit me, I would land across the room.” Another time, the husband steals her bag of candy that her father had gifted her during a visit, something she says she treasured deeply, and throws it in a fire.

Soon after, her father takes her to a new foster home in Pictou Landing. In this home, she lived with a couple and their 14 year old son. She describes one night, hearing the father giving the son a severe beating in the next room. After this, she lived in constant fear of receiving the same treatment, and always did exactly as she was told, “no matter how unusual the request.” Right up until the day she sat down to write her book, she says she wondered why the son received those severe beatings.

The next foster home she went to was in Millbrook. The sexual and mental abuse she endured at the hands of the husband at this house, she describes as “the only flaw”. Which is strange as before this, she had mentioned being consistently tormented by their biological children, who would physically assault her and steal her things.

She says the approval the man gave her for doing these sexual favours “meant something to her”, as she was always seeking approval.

Finally, after months of suffering this abuse, the matter was looked into by people on the reserve after she’d told a friend about it. The foster mother blamed 7 year old Rita for what happened, calling her ungrateful. She cried tears of regret, wondering if she should have kept her mouth shut.

After she was removed from the abusive home, she was placed in another home in the same reserve. Here, she was taken care of by an old lady, who she describes as someone who was always cross and swore a lot. She slept on a bed of straw covered with coats.

This old lady had an older son, a man, who Rita says did not like her, and made her sit on a step below the doorway to eat all of her meals because he “didn’t like seeing her at the table”.

Her chores at this house included caring for the lady’s sick husband, who had TB.

She left this house soon after the husband died.

At 10, after her own father’s death, she went to live in Oxford with her older half brother William. Here, she learned how to make home brew (homemade liquor). Her brother and his wife would leave for work 2-3 days at a time, leaving her alone with a list of chores to do, including making the home brew, and going grocery shopping, while they were gone. She recalls her foster mother, her brothers wife, forcing her to drink the brew one night, threatening that if she didn’t, she would throw her out of the house.

On this night, she got sick from the alcohol, went outside and fell asleep wrapped in a blanket in the snow until someone found her. She wanted to leave this house after almost 2 years as the drinking her family engaged in became increasingly frightening. She says she wrote a letter to an Indian agent, requesting that she be picked up the following week because she wanted to go to the residential school in shubie. As requested, the Indian agent showed up a week later, to take her away. She says she was thrilled.

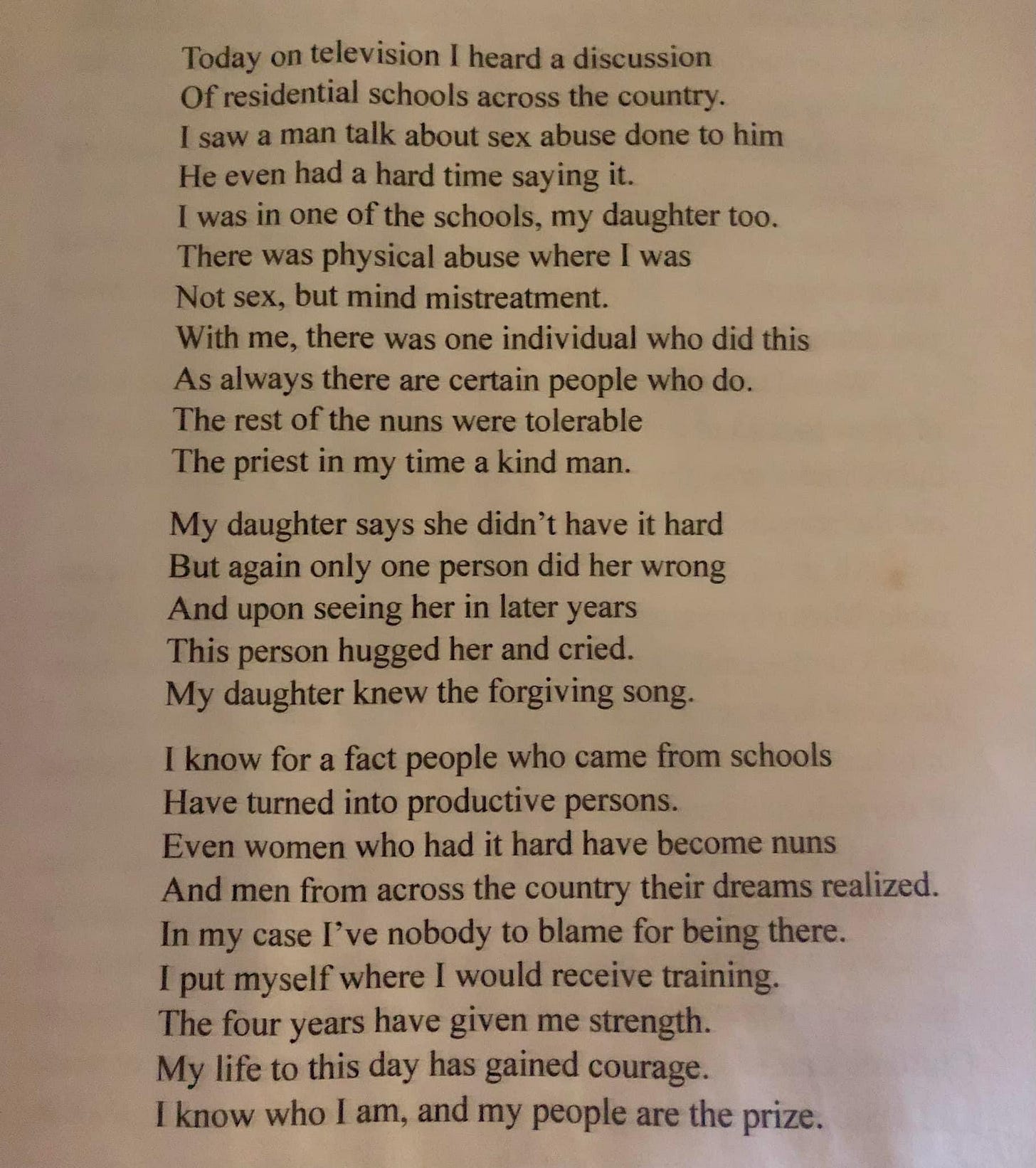

The 4 years she spent in the school, she describes as “memorable.” The “bad things” she cites as “being told to do everything military style”. (Which of course would be hard for any child who hadn’t any experience with consistent structure or discipline.) Although some of these nuns were mean, a few were very kind, and she would befriend the kind ones as well as the priest, who she describes as a gentle man.

She talks about one especially kind nun whom she loved working in the laundry room with, who’d tell her stories and bring her a treat of candy or chocolate everyday.

This nun would become the only person in her life to gift her a Christmas present each year, something she remained grateful for the remainder of her life, as she recalls feeling envious of the many other children who would receive parcels from their family in the mail during this time.

She talks about getting to ski, skate and sled during the winter.

In the summer, she talks of going swimming, having cornflakes and juice for breakfast every morning (something that was a treat the rest of the year except for holidays), going on picnics, berry picking, and having lots of toys to play with since 70 out of the 100 girls there would return to their homes for summer break. They would be allowed to sleep in, skip church, and have permission to leave school grounds for walks. She believed the nuns’ motivation for supplying the children with treats and activities during the break was so that they would feel less lonesome.

Most of the children would have regular visits from relatives throughout the school year. She recalls of feeling envious of these children because her brother Soln had only come to visit her occasionally.

She leaves the school after 4 years. The nuns helped her find a job at an infirmary in Halifax where other indigenous women worked as nurses.

That was the end of her chapter entitled Girlhood. She mentions only hearing others tell stories about abuse at the school. But never elaborates on it. Why? Why would she only elaborate on the abuse she saw and endured on the reserves but not in the IRS? To the unbiased eye, compared to earlier parts of her childhood, the school sounded like a saving grace.

(This post originally appeared on Karli’s Substack).

Thanks for reading. For more on Indian Residential Schools, read When the Abused Becomes the Abuser

Follow Woke Watch Canada on X - @WokeWatchCanada

Support Woke Watch Canada by upgrading to a paid membership:

Or, by contributing to our Donor Box:

I spoke with older FNs in Pemberton BC during the 80s. I was early 30s they would have been about 40. Many had gone to IRSs. They spoke well of it. One good buddy of mine said he learned to read and write. He wasn’t getting that at home. I didn’t hear any of the horror stories we hear about. But we know pedos go to where they can control and abuse children. I am sure some did things. Many wouldn’t.

Can you recommend any books by indigenous authors who wrote about their positive experiences with Residential Schools?