Ottawa's 'Special Interlocutor for Missing Children' heads a growing empire but so far she has identified not a single unmarked grave that is actually a grave of a named 'missing' child.

By James Pew, Brian Giesbrecht and Nina Green

This essay was originally published on Dec. 19th by the Dorchester Review.

ON JUNE 8, 2022 the federal government appointed Kimberly Murray as Independent Special Interlocutor for Missing Children and Unmarked Graves and Burial Sites associated with Indian Residential Schools. An indigenous activist, Murray was Executive Director of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission from 2010 to 2015. At the time of her appointment as Special Interlocutor, she was “Executive Lead for the newly created Survivors’ Secretariat at the Six Nations of the Grand River, working to recover the missing children and unmarked burials at the Mohawk Institute.”

Although the statute under which her appointment was made has never been identified, Murray’s job description as Special Interlocutor is very specific:

The Special Interlocutor will work closely and collaboratively with Indigenous leaders, communities, Survivors, families and experts to identify needed measures and recommend a new federal legal framework to ensure the respectful and culturally appropriate treatment and protection of unmarked graves and burial sites of children at former residential schools.

Murray has been specifically tasked with developing a new federal legal framework for protection of unmarked graves of children of former residential schools.

Whether this is a constitutionally valid job description is open to question since it appears to delegate to her the function of the legislative branch of government.

Moreover there is no evidence so far that the activities in which she has engaged since her appointment relate to that job description. She has hosted two Gatherings, one in Edmonton in September and another in Winnipeg in November. Both took place in the almost complete absence of media coverage, despite the fact that a keynote speaker at the Edmonton Gathering was Dr Chile Eboe-Osuji, former President of the International Criminal Court, who told attendees that “There is no pathway to the International Criminal Court for the situation of the historical Indian residential school system in Canada.” In other words, because of the Rome Statute to which it is a party, Canada cannot be prosecuted by the ICC for genocide since the ICC’s mandate does not extend retroactively beyond its foundation on July 1, 2002. This should have been breaking news in Canada, but received no coverage at all because Kimberley Murray had not invited media to attend Dr Eboe-Osuji’s address. Amid a plethora of ceremonies, nothing of note appears to have transpired at the second gathering in Winnipeg. A Progress Update Report issued on November 10th speaks repeatedly of “Sacred Work” and states that:

The search for unmarked burials and the recovery of missing Indigenous children must be governed by Indigenous laws, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.

The question thus remains: How is Kimberley Murray carrying out her mandate to create a legal framework for the protection of unmarked graves since according to her progress report she has so far not identified a single unmarked grave in Canada which she can confidently state is the unmarked grave of a named child who died while enrolled at an Indian residential school?

Neglected Cemeteries on Reserves

For indigenous peoples, Christian burial and cemetery maintenance were introduced customs, with the result that after the residential schools closed and the Oblates and Protestant missionaries departed, community cemeteries on reserves were often left to the elements. Cemetery perimeters eroded, fences disappeared, and the wooden crosses which had marked the graves vanished with the passage of time.

The century-old Kamloops Band cemetery, for example, has hundreds of unmarked graves, some with old wooden and iron crosses lacking names, others with no crosses at all.

[Photos by a correspondent of The Dorchester Review. Note that this is a couple of miles from the apple orchard, near the old Residential School, also on the reserve, where Dr. Sarah Beaulieu rolled her GPR.]

Murray and other indigenous activists have distorted this neglect of community cemeteries on reserves into a narrative that conjures up images of foul play and clandestine burial.

On the contrary, it is well known that most children who died while enrolled in residential schools died of tuberculosis and other diseases. While some died at the schools, where they received nursing care from school personnel, most died in local hospitals where they received the best medical care available at the time from the same doctors who treated patients in the larger community. A few died in accidents or ran away and died of exposure.

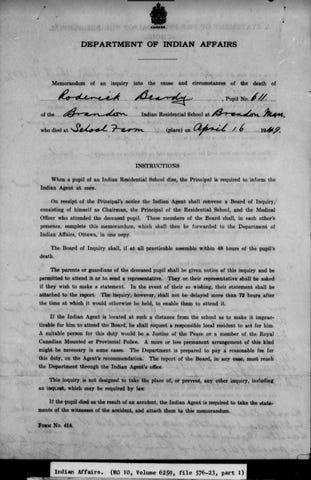

Details of these children’s deaths were routinely registered with provincial authorities. Although the amount of information included in provincial death certificates varies from province to province, most provinces recorded the cause of death and the place of burial as well as the name of the physician who attended the child prior to death, and whether there was an autopsy. Many death certificates were signed by parents. As well as requiring the routine registration of the children’s deaths with provincial authorities, the Department of Indian Affairs mandated that the local Indian Agent conduct a formal inquiry into the death of every child who died while enrolled at a residential school (See photo below). Records of these inquiries for many residential schools can be found in the Library and Archives Canada School Files Series.

In some cases, particularly in the early years of the residential school system, when a child died at a residential school the parents could not be easily reached because they were living in isolated semi-nomadic communities, or were away on traplines. In other cases, the distances were too great for it to be practicable to return children’s bodies to remote reserves for burial. This was particularly true in the case of industrial schools which had been deliberately located near towns and cities not close to any reserve. In such cases the school had to provide its own designated community cemetery in which children (and in some cases, adults) who died at the school could be buried, including orphans who had no family to whom their bodies could be returned. Brandon Industrial School is one such example.

Nonetheless, in all cases the children received Christian burials, and in the vast majority of cases their bodies were returned to their home reserves where they were buried in community cemeteries.

That so much time has passed, that burial records and gravesites in reserve cemeteries have been lost, that some parents lived too far away to attend their children’s funerals, and that these events took place over such a vast geographic expanse, a massive area spanning the different locations of schools, reserves, hospitals, cemeteries, and nomadic encampments in the Canadian North, at least partially explains the confusion which currently exists.

Despite these obstacles, more than 600 death records for students named on the NCTR’s Memorial Register have been verified by independent researchers through provincial vital statistics agencies and federal government documents in the School Files Series. This research has been done at the researchers’ own expense: there are no vast sums of taxpayer dollars available to private researchers. Unfortunately, the results of their work have been ignored by the NCTR, which has refused to amend its Memorial Register despite having been advised that these children are not buried at residential schools but on their home reserves.

Kimberley Murray’s mandate

Because so many thousands of grave sites have been lost to time, any comprehensive attempt to locate them in community cemeteries on reserves, and to match the names of residential school students to these unmarked grave sites, would be a massively expensive and time-consuming project, and in fact impossible without exhumation in community cemeteries, which is unthinkable.

In any event, as noted above, it's not at all clear that Kimberley Murray intends to do this, particularly since she was apparently unable to find the death record of even a single child while she was Executive Lead at the Mohawk Institute. Private researchers have found Ontario death records for a significant number of students at the Mohawk Institute, but Kimberley Murray was unable to do so.

Murray’s plan appears to be quite different. It seems clear she is continuing to promote the myth that thousands of residential school students disappeared without a trace, with the implication that they met their deaths as a result of deliberate acts by residential school officials, and were secretly buried with their parents never notified, and their deaths never recorded.

So far, Murray’s activist narrative is accepted without question, despite the fact that there are no police records or media reports throughout the history of the residential school system of any parent searching for a child who went missing from a residential school. Not one of those thousands of children who supposedly vanished in a murderous residential school system had a parent who went to the media or the police for assistance in finding a missing child.

It appears Kimberley Murray has placed herself in charge of a growing empire that will do nothing more than search for unmarked graves in community cemeteries that have not been properly maintained and in some cases have been long forgotten. Because the majority of these community cemeteries are associated with Catholic and Protestant missions, Murray will obtain generous permanent funding by guilting the government and the tax-paying public into believing that something sinister took place to children who died while enrolled at Indian residential schools located near these community cemeteries — a belief that is utterly false.

___

Thanks for reading. For more on Special Interlocutor Kimberly Murray read - The Special Interlocutor and the Odds of Future Reconciliation

Kimberley Murray will not find proof of a single missing or murdered student because there is none. Legacy media will continue to bury the truth that no such children are buried.

A rational objective essay. Keep up this important work. I taught at the Grouard mission school of St. Bernard's, Alberta, in 1968-9. We had no school deaths. I visited the local cemetery which had numerous wooden crosses ,one of which still stands out in my memory, "Billy". Obviously much loved and sorely missed. The area was deeply grassed and not tended while I was there.

In 1987-90 I ran a maintenance program for the We La La Lu in Alert Bay BC. The island had St. Mikes residential school in the community. The Island on which Alert Bay stood had a new cemetery which was mowed and tended occasionally and I believe was used by both indigenous and other peoples. The old indigenous cemetery South East of the ferry and on the water front had many totem poles in reasonable state of repair. However local elders declared that the coast road running past it was placed over graves. This would have made them below the extreme high tides. The road was duly blocked off which forced the traffic up, across and down a steep hill terminating in a "T" junction which was extremely dangerous. The department of BC highways surveyed the area for a road to project out to sea around the alleged graves. However they said it was possible to conduct a ground penetrating radar search which could indicate whether there were potential grave in the area and thereby eliminate a road construction expense The elders said without a doubt there were burials and refused to allow the use of ground penetrating radar . As a consequence the newly built road from the ferry takes a long curve around the cemetery foreshore On talking to the BC Highways office in Courtenay I found out it cost $1,000,000 to construct this detour. Those are 1990 $,s!! You might want to follow this up. Although 30 plus years ago my memory is sound.

I had occasion to visit Kincombe inlet further up the coast from Alert bay which was only accessible by float plane or by boat. I could not gain access to the cemetery because of the blackberry bushes which are voracious in this coastal climate. A visit to Hopetown not far away was as difficult to access and had their gravesite on a small rocky islet with little vegetative growth and coffins were stored in small wooden houses placed over the rocky terrain.

Maintenance and custom of gravesites , in my experience ,vary greatly. My own experience in locating my ancestors grave in Weybridge Surrey, UK was unsuccessful although we did find a headstone laid against the old brick wall with the family name. The whole area was grassed. Neither my father or I were unduly concerned. We came from the earth and to it we all return.

As an aside my British community of Highgate ,North London ,is the location of the Victorian effort to systematize burial sites with the famous early West cemetery of marble mausoleums and famous names and the later East cemetery where Karl Marx is buried. I had the experience of seeing Yuri Gagarin's visit to this site.

I hope I have given a balanced overview of my experiences and contributed to a breadth of knowledge.