When Family History Turns out to be Family Myth-tery

Respecting those who did what they had to in order to survive

By

This article originally appeared on Medium.

When I was young, this lady and her several sons and very funny husband used to come and visit us about once a year. We loved having these guys over because then we kids had enough people to play a great game of ‘kick the can’ outside. My Mom always seemed very emotional about this woman’s visit but as far as I knew she was just a really good friend from her past. It was not until I was grown-up that she confided in me that the woman was my aunt, and those kids were my actual cousins!

How could this be?

It turned out that my mom’s mother had died shortly after childbirth. As farm wives often had to do, she had gone out to wrestle the milk cow back in after it had gone off across the prairie and then, having just recently given birth, she started hemorrhaging.

But wait. If my mom’s mom was dead, then who was that woman parading around as my grandmother all these years? My grandmother’s sister. After my grandmother died, the only other woman my grandad knew well was her sister back in England, so he asked her to marry him. She had been helping her father deliver milk in their small town, but her father had just broken his leg and could not work anymore. So, whether by bad luck or happy coincidence, she decided to accept the marriage proposal, come to Canada and be mother to her sister’s three little kids.

What?!!

Why did we never talk about these things?

Because it turned out that my aunt was the baby that my biological grandmother had given birth to — but my grandfather already had three small children to care for and the childless neighbours had stepped in to help. (Before my biological grandma’s sister arrived.) Their help became permanent, and whether there was an official adoption or not, as long as that couple was alive, we were never to speak publicly of the relationship of my aunt and her family to ours. My aunt was that nice lady who would visit us with her many fun-loving sons.

I grew up never realizing that the cousins closest to me who we visited most often were my step cousins and my real cousins were those crazy kids that would visit once or twice a year.

Despite my mom’s aunt agreeing to marry my widowed grandfather (and thus become my grandmother), it turns out that then my mother, a girl of about 13, was sent overseas to be a live-in companion/domestic/caregiver to her grandmother in England whom she had never met before. There she spent the next 18 years of her life, never seeing her baby sister until she returned to Canada after the war. At which time, no one would publicly talk about their relationship out of respect for the adoptive parents who were still alive.

I bring up this story because of some of the awkward family history revelations for some First Nations people that would disrupt the telling of their family history and our understanding of Canadian history.

We often hear First Nations peoples say that “my grandmother was forcibly taken away to residential school at age 5” — but the documented facts are that children had to be enrolled by their parents. Children were not allowed to go to residential school until they were seven… except if the family was destitute, having serious problems with violence or alcohol, or if the child was an orphan.

Much of this is documented in the various records of the Indian Residential School enrollments, quarterly reports, Indian Agent correspondence, diaries of sisters and brothers who ran many of the schools. It takes some patient navigating but it is all there.

Thus we find that the grandmother of a famous person like Murray Sinclair, former Commissioner of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, ended up at the Fort Alexander Roman Catholic Indian Mission because her mother died. Though her father remarried, much like the story of Snow White, the new wife wanted to have her own family and not care for the children of someone else. As orphans, they were taken in by the mission. This was a common occurrence back in the day. Yet Sinclair has derided residential schools, where remarkably similar stories of orphans being rescued happened a lot.

In so many cases when the documented history is checked against the family ‘myth-tery’ there is often a surprise. Chief Wilton Littlechild was also one of the Truth and Reconciliation Commissioners, a body which portrays Indian Residential Schools as having been violent, abusive, and guilty of cultural genocide. His biography notes that Chief Littlechild entered residential school at age six, one year younger than enrollment age. He was from a large family of seven sisters and four brothers. His grandparents raised him. Littlechild’s grandfather hosted Indian Residential School picnics at his yard as the school was on reserve. It is surprising to learn that Chief Littlechild was allowed to stay at Indian Residential School until he was 20, despite the leaving age normally being 16. If it was such a bad place, why stay four more years? And if government funding ended at age 16, why was he allowed to stay longer? If it was such a terrible place, why didn’t his grandparents take him out and keep him home?

In the case of Chief Dan George, who was enrolled by his parents in Indian Residential School when he was 4, (because he was said to be inseparable from his older brother, so they made an exception), he actually cried when he had to leave Indian Residential School at age 16 because he loved learning and knew he had so much more to learn. He loved it there.

Many times, like my Mom did, parents deceive their children with family myths and light lies so that other people will not be embarrassed by things kids might say or do, or so that the family member avoids any backlash from their child, especially in such sensitive personal circumstances.

Imagine if your family was so poor, they had to give you away, or so suffering from violence or alcohol that it was not safe for you — so the police took you away; or that your parent(s) died and there was no one left to care for you, so the Indian Agent would send you away to Indian Residential School so that you would survive.

You were a child then.

All you would remember is that painful separation from the ones you loved. If you were told that the government forced you to go, then it is not your parents’ fault! Then you can turn your anger on the government.

Later in life, how many parents would want to say to their child — “We were starving. I could not afford to feed you or keep you. I sent you to a place that would keep you alive.” How many parents would be able to say to their grown-up child “I was struggling. Your mother and I would drink and fight all the time. The police took you away after I nearly hurt you.” How many aunties could admit “We loved you and your brothers and sisters, but we could not take you in after your Mom died. We already had seven kids. You had to go to Indian Residential School. There was no other choice.” Gives a whole new meaning to the term “residential school survivor,” doesn’t it?

One Indigenous woman, in telling her story of alleged genocidal activity at an Indian Residential School, went on to reveal that when she lived at Grandmother’s home as a child (as her mother was divorced), her uncles who also lived there, brutally beat her, and sexually abused her. She did not mention having received any such treatment at the residential school. At home she recounts that ‘there was lots of drinking and violence on reserve.’ She used to have to hide in the sweat lodge or haystack to escape her uncles; then later when she was age 7 her grandmother took her to see her siblings off to Indian Residential School, but she was picked up, too. Since children had to be enrolled, perhaps her grandma wanted to send her to a safer place than home, where her uncles beat her with sticks and even once bullwhipped her and her brother (as she tells it). Maybe it was easier for her Grandma to say ‘I didn’t know they would pick you up and take you away to school, too’ than to be seen as being heartless for sending her away to what she hoped would be a safer place for the little girl.

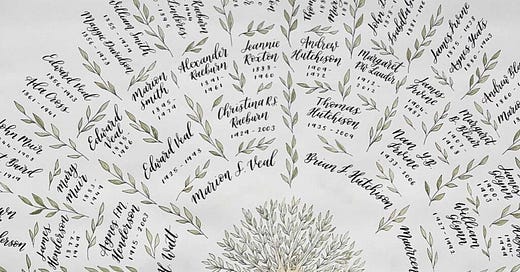

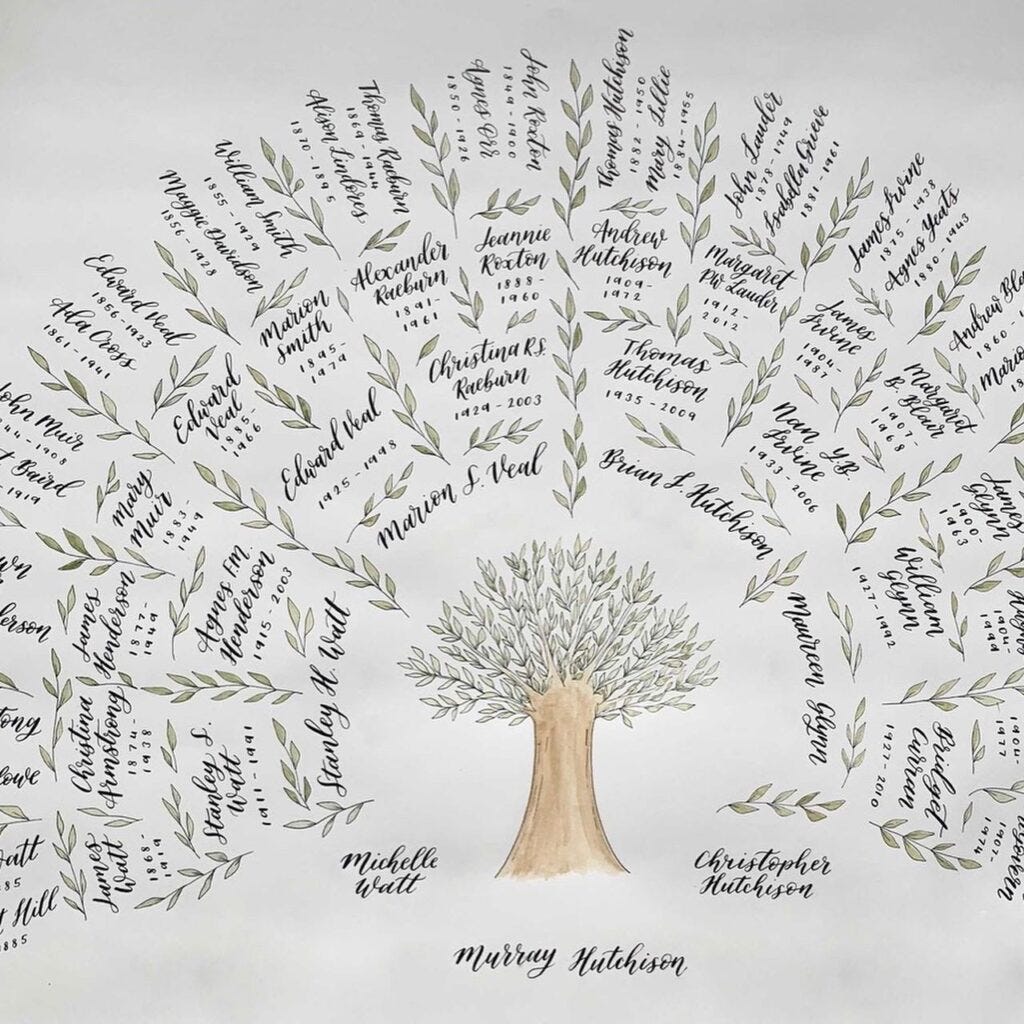

It is often a shock to learn the true story of your family history. And strange things come out of it. I remember once, as an adult, my eldest cousin from the ‘kick the can’ story was visiting me, and we started talking about our ‘real’ grandmother who had died following his mother’s birth. He was very much into genealogy, and I assumed he knew more about her than I did — but he did not. It suddenly struck me that maybe he also did not know what she looked like. He said he had never seen a picture.

I had a spare copy of a picture of my grandmother with my grandfather and the three kids — and as I gave it to my cousin, we both looked at each other when the photo passed between our hands. It was as if we had suddenly bridged a hundred years of time. We both teared up over sharing the image of our biological grandmother, his first time ever seeing her… a woman of our family myth-tery. She was the root of our very existence.

What people have been told about the family is not always the truth, which is why we cannot rely on family stories alone, especially if we are making serious accusations like genocide that stem from historical events.

In my opinion, you have to be prepared to be forgiving because circumstances back then were nothing like life is today. People often had to make difficult choices and like that poem by Robert Frost “Two roads diverged in a yellow wood, and knowing I could not travel both and be one traveler, long I stood…” Once the fateful decision is made, lots of things change in ways that can never be changed back.

I do not know if my step grandmother ever regretted coming to Canada and becoming an ‘instant mom’ to three children, and then mother to more of her own. Since I never knew she was not my biological grandmother until after she died, I just accepted her as the sweet, kind, optimistic woman that she was. How lucky my mom and her siblings were that she was willing and able to raise all of the kids and not abandon those who were not her own.

I was shocked to learn these things of my family history, but as I learned more about how difficult things were back then, I realized my Mom had done the right thing by creating a nebulous family myth — one that respected those who did what they had to in order to survive.

Michelle Stirling is a member of the Canadian Association of Journalists. She researched, wrote, and co-produced historical shows about Southern Alberta under the supervision of Dr. Hugh Dempsey, then curator of the Glenbow Museum

___

Thanks for reading. For more from this author read Every Living Child Matters Most of All

Thanks for reading. For more from this author read Senate Testimony Reveals Missing Children’s Names and Graves are on Ancestry.com

There are now two ways to support Woke Watch Canada through donations:

1) By subscribing to the paid version of the Woke Watch Canada Newsletter for - $7 Cdn/month or $50 Cdn/year.

2) By making a contribution to the Investigating Wokeism In Canada Initiative, which raises the funds necessary to maintain and expand Woke Watch Canada’s research and investigation into Dysfunctional Canadian School Boards, Education, Indigenous Issues, Free Speech, and other areas of Illiberal Subversion and the Canadian Culture Wars.

Thank you Michelle for a very touching and insightful article. I agree completely with you that scapegoating residential schools is a coping mechanism for dealing with traumatic childhoods. Certainly the case of Wilton Littlechild, in the words of Winston Churchill, "is a riddle, inside a mystery, wrapped in an enigma. It would be really interesting to know why he stayed all those extra years in a dangerous environment where babies were thrown in ovens and children buried in mass graves. Was he a Kapo guard supervising the other prisoner children ???

The truly bright side of your article was the information on the iconic western actor, Chief Dan George.

His movie roles along side of Clint Eastwood are remembered fondly by an entire generation of movie goers as well as his famous line, "today is a good day to die" which was always averted in the film. His success as a famous entertainer should be considered as a stunning example of how initiative triumphs over adversity.

"Palma non sine pulvere."

Dare to try.

What a brilliant and thought-provoking article! And so true. Families often create myths about various members to conceal their sense of shame and elevate their status to others. I learned some truth when my father had vascular dementia (mild at that stage). One of his symptoms was disinhibition. He told me things about certain family members that he never would have told me before having this condition. I learned, for example, about marital troubles with his parents which no one had talked about. Also (and this made me chuckle) my mom's desire to have sex with him before their marriage when her family reputation was that of a pure, pristine "angel". From a cousin, I learned some truth about one of my aunts. A woman who came across as sweet and fun-loving to the outside world but who could be very abusive to her immediate family. (I actually got a glimpse of her "Ms. Hyde" personality after a death in the family.) From Stirling's article and our own experiences with family myths, it's hard to take the mantra about abusive residential schools seriously. Yes, I do believe there were certain schools and certain individuals in those schools who were abusive. But I'm sick and tired of my country being forced to take the blame for all of the suffering caused by aboriginal peoples' own families, not the residential schools.