Ancients Vs Moderns

Books, Education and the Life of the Mind

Woke Watch Canada is a reader-supported publication. Please consider becoming a paying subscriber or making a one-time or recurring donation to show your support.

By James Pew

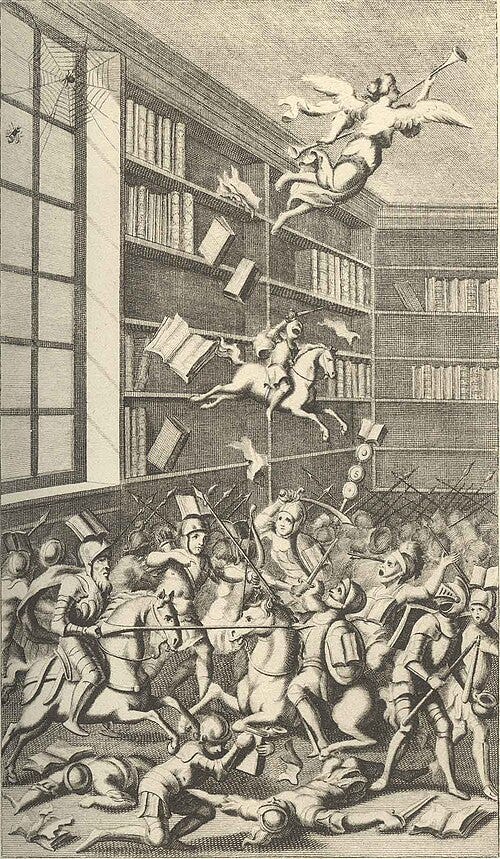

“...instead of dirt and poison, we have rather chosen to till our hives with honey and wax; thus furnishing mankind with the two noblest of things, which are sweetness and light.” - Said the Bee to the Spider in Jonathan Swift’s Battle of the Books

The dynamism of the Western intellectual tradition can be represented by the reciprocating motion of a tug of war, where the tension exists between curiosity and doubt, credulity and skepticism, faith and reason, empiricism and erudition, and of course, incremental adjustment and its arch nemesis, radical innovation. Although perhaps, as some have imagined, the history of this tradition may be more like a rotary movement, a recurring cycle of ups and downs. Either way, the apparatus required to build a theoretical framework utilizing such metaphors is a deeply Western phenomena.

This extends to the machinery of the metaphor itself. Western intellectual tools lead to habits of mind which promote not only the inquisitiveness to ask daring questions, but the skepticism and doubt to seek falsification. They also encourage the creativity for comparison and analogy, and the credulity to locate patterns of truth as they cast vague impressions in fleeting shadows flickering under dim and distant lampposts on ghostly walkways long vacant of the hustle of life, the scholar plugged into the Western intellectual traditions will pursue them unendingly. His relentless inquiries will lead to those remotest corners long untouched by vivacity, and as history has shown, his commitment, studiousness, and not just attention to, but immersion into the minutia of detail will help uncover those treasures which ignite the imagination as their full essence reveals under the bright beams of examination. This is the Western way, where the sheer abundance of facts and details can sometimes get in the way.

The history of the West, its ebbs and flows, its victories and failures, its triumphant expansions and drawn out collapses, involves a thread of continuity stemming from the earliest days of Antiquity – the 8th century B.C. when the Greeks received Homer’s epic poems. The Western narrative links together a succession of consequential events leading us through stages of development where ultimately, at the outer edges of modernity we ask if collapse, of the type our Roman ancestors experienced, may once again be on the horizon.

Western epistemological traditions have themselves often been the source of much conflict. In the modern period, a culture war emerged over them. The clinical pedantry of the new versus the established erudition of the old could only have resolved itself within a rational middle ground. Then as now, it matters most for what purpose scholarly tools were/are employed. In the early modern period, some scholars felt their primary duty was to direct the bulk of their intellectual resources toward the study of antiquity, while others had “a presentist faith in the utility of modernity alone.”1 In the latter case the so-called new science had provided a reason, or perhaps an excuse, to leave behind what they viewed as an outmoded form of acquiring knowledge: the liberal arts, which had been so recently renewed by the Renaissance humanists.

Further, as will be discussed below, some ancient tools of the Western intellectual tradition, especially those in the field of history, have a tendency to universalize seemingly irreconcilable particulars. An impulse to find a reasoned compromise eventually led to the proposition that “antiquity and modernity stood in dialectical relationship to one another; the latter could not be understood without reference to the former.”2

That dialectical relationship appears often in the form of polemical arguments where deeply entrenched seemingly incommensurate philosophical positions vie for advantage. Whichever side comes out on top, sets the course of humanity’s progress (or lack thereof). In the waning years of the 17th century, a noteworthy manifestation of one such contest became known as the ancients against the moderns. We will return again to this consequential struggle after a brief explication of some relevant epistemological artifacts of the Middle Ages, which will assist in painting a picture of the world inherited by the Renaissance humanists who figured so prominently in the early history of modernity.

The Medieval World of Gloss and Lemma

The Latin glōsa, which comes from Greek γλῶσσα, refers to an obsolete or foreign word requiring explanation. It appears in the English language in the 14th century as gloze, which at the time was borrowed from the French glose. But by the 16th century its spelling had been updated to gloss in order to more closely imitate the more illustrious original Greek form. The annotation of older texts, the practice of inserting glosses, and correcting and expanding on the ideas of the original authors was a common pursuit of medieval scholars. Eventually their tools evolved, a collection of glosses became known as a glossary. Compilations of glossaries led to the first dictionaries. This was the beginning of lexicography and of an expansion of the intellectual tendency or habits of mind involving labeling, compartmentalizing, organizing and systematizing, comparing, cross-checking and correcting which were developing continuously in the scholarly circles of the middle ages, and which would soon lead to a veritable intellectual conflagration.

Another clever medieval invention of early lexicography is the lemma, which refers to a minor theorem inserted into a more important theorem thereby helping to reinforce the main theorem. Or, as Merriam-Webster has it, “an auxiliary proposition used in the demonstration of another proposition.” But it can also refer to the headings or subheadings found in various texts. Because headings are there to denote the topic or motif of the exposition that follows, lemma is a categorizing term meant to help organize or insert specific arguments and sub-arguments into a text. The habit of dividing a work into sections, and interposing comments, via lemma, combined with the general habit of annotation (correcting, collating, emendating, and glossing). In more ways than one, like the gloss, the lemma was a device which by its invention practically tempted medieval scholarship along a path that would later lead to accusations of pedantry.

In fact, a tradition of commentary, annotation and exegesis, was firmly in place at the outset of the early modern period. Many eminent scholars of the day were expositors and glossators. They were the qualifiers, the correctors, and in some cases they even considered themselves the co-authors of the texts, many of them classics, which they felt were lacking in one way or another.

Of course this explicatory world of gloss and lemma inevitably led to conflict. When one adds to the uncountable controversies which arose over the accuracy of translations (either from Greek or Latin), and over historical validity of the accepted provenance concerning ancient works and artefacts, the possible points of mis-interpretation, misunderstanding, incorrect correction and disagreement multiply. The blowout was inevitable.

But there is more to these matters than differences of opinion on any given set of concerns, no one specific gloss or lemma led to the creation of the two distinct sides (ancients and moderns) which, locked in unbreakable opposition, would emerge in the early modern period. Rather it was the general pedantry, the over-reliance on the new tools of scholarship, the over-emphasis on the subjective opinions of expositors, the countless trivial additions, emendations, and corrections, and perhaps most contentiously, the mis-translations. There were some who felt these activities were destroying the illustrious tradition of erudition firmly established by the time of Augustan antiquity. A tradition which exalted beauty as much as truth. There was a fear of an imminent culture of faithless confusion and ugliness, an unintentional mutation of the earnestly punctilious but misguided attempts by Moderns at finding truth. It was the beginning of a battle that would rage for decades to come: Moderns vs Ancients. It was the beginning of modernity.

The Early Enlightenment 1685 - 1715

In the august years of the seventeenth century something strange occurred within the minds of Western Europe’s intelligentsia. This new oddness did not have a singular theme nor a sole point of origin, however its spirit was understood, in a word, was felt, at first slightly then later deeply, as all consequential movements of humankind are apt. Indeed, as its novel and variegated premises spread, without the full awareness of those navigating the uncharted tides, humanity crossed a rubicon. We have yet to safely land on the opposite side, still forging ahead through those murky and foreboding waters, reminding ourselves what Andre Girade wrote in his novel The Counterfeiters: “One does not discover new lands without consenting to lose sight of the shore for a very long time.”

Rivers of ink have been spilled over the intricacies and controversies which occurred within the immediate decades both before and after the end of the 18th century. The following paragraphs will highlight a small collection of examples. One of the most significant works on this period is Paul Hazard’s1935 The Crisis of the European Mind, in which he proclaims “One day, the French people, almost to a man, were thinking like Bossuet. The day after, they were thinking like Voltaire. No ordinary swing of the pendulum, that. It was a revolution.” Indeed it was, although there were causal antecedents, and more than a few moderate voices caught in the fray between the reactionaries and the revolutionaries.

From Luis Depre’s The Enlightenment and the Intellectual Foundations of Modern Culture:

“I assume that the Enlightenment was indeed a distinct epoch in modern culture. Yet this assumption does not entail that there was no continuity in the flow of modern thought nor that it was a homogeneous movement. The Enlightenment remained a project; it never became a full achievement. It continued to question the past and to anticipate the future, but various groups and individuals held different views concerning past and future. It has become increasingly common to exclude traditionalist thinkers such as Vico, Malebranche, Burke, and Herder from the Enlightenment as if they belonged to what Isaiah Berlin has called the Counter-Enlightenment. Yet these writers were not reactionaries. They held modern, though different views concerning their epoch’s relation to past and future, and they may have exercised a deeper influence upon future thought than radical critics like Voltaire or Condorcet did.”3

Concerning the French scholars of the period, Dan Edelstein argues in his The Enlightenment: A Genealogy that they were “less epistemological than narratological,” in that they did not devise any new methods of reasoning or depart from conventional understandings of the world, “rather, they offered a seductive account of the events and discoveries of the past century, in conjunction with a more overarching history of human civilization.” It was their belief that the scientific revolution had inspired a “philosophical spirit” which carried over to the “educated classes, institutions of learning, and even parts of the government.”4

In the 2005 edited volume Historia: Empiricism and Erudition in Early Modern Europe, Gianna Pomata and Nancy G. Siraisi compiled “several essays that investigate…what historia meant in the early modern vocabulary of knowledge and…in early modern encyclopedism.”

And, Joseph M. Levine examines the work of some of the key literary figures and historians of the period relevant to both the English and French episodes, known respectively as the quarelle and the Battle of the Books, in his 1991 volume The Battle of the Books: History and Literature in the Augustan Age.

Perizonius and Universal History

“Perizonius worked for a via media between the pyrrhonists of his own time and the credulous traditionalists of any time.”5

Founded by the Greek philosopher Aenesidemus in the first century B.C., pyrrhonism is the suspension of judgment concerning the truth of all beliefs. It is, to an obvious fault, ultra skepticism. Herein lies the origins of the Moderns pedantry.

Turning to the work of Renaissance humanist scholars, like the highly regarded Dutch classical academician Jacob Perizonius, who was an eminent figure in the pan-European Republic of Letters until his death in 1715. Best remembered for his struggles against historical Pyrrhonism, Perizonius detected an exaggerated form of historical skepticism which questioned whether anyone could really know anything at all about what happened in the past, reflected in the pedantic ways of the moderns inspired by the scholarship of the new science.

The ancients, along with moderates like Perizonius, felt that convoluted pursuits which shed light on trivial details or nothing of interest and in more ways than one seemed to have dispensed entirely with the concept of utility, were not worth the time and effort. Perizonius pragmatically argued for a compromise, a via media, between skepticism and credulity. A judiciousness he would demonstrate throughout his life distinguishing his moderate views from the more polarized ancients and moderns.

Perizonius, among other historians, contributed significantly to the widely accepted view that a catalytic process of renewal was achieved through the rediscovery of ancient texts at the dawn of modernity (the Renaissance). This view was part of a scholarly genre with a tradition stretching back to antiquity known as historia universalis, or universal history, which Perizonius focused much of his life’s work on developing. Today universal history is called world history.

“Universal history promised a union of antiquity and modernity, which Perizonius saw as a solution to those conflicts and quarrels that so divided his contemporaries.”6 In addition, he feared that history might be repeating itself. His framework of historia universalis saw historical periods of collapse due to descent into corruption and barbarism, leading to eventual revival by the rediscovery of ancient wisdom. The Renaissance had its counterpoint to this cycle in Augustan Rome, which is considered the paragon of Roman cultural achievement. Not only was this period in Roman history indicative of ancient revival, but a subsequent period not long after culminated in collapse due to its unmitigated corruption and the barbarism that followed Rome’s greatest cultural epoch. The Western Roman empire fell in 476 AD. Perizonius gives credit to such luminaries as Petrarch, Erasmus, and Scaliger whose works help make it well known that the humanist revival during the Renaissance both drew from and paralleled Augustan Rome, however, Perizonius completed the comparison by claiming to detect the same symptoms of collapse during his time at the dawn of the 18th century.

“In Perizonius’s mournful estimation, his own times resembled the time ‘immediately following the Augustan age,’ in which, according to Seneca, many Romans ‘built libraries with as many volumes as possible’, but still absorbed almost no learning. Like the Rome of Seneca, the decades around 1700 seemed redolent of autumnal lateness. They threatened the repetition of that drama that had ultimately resulted in antiquity’s end.”7

In many ways Perizonius resembles Dr. Richard Bentley, a prominent figure of the British episode of the feud between ancients and moderns known as the Battle of the Books. Although Bentley is portrayed as an insufferable pedantic by the English Scriblerians, upon closer examination he appears to have a similar brilliance and much of the same approach to scholarship as Perizonious. However, as will be elaborated in the relevant lemma below, his British detractors were far less generous in their assessments.

It’s not a detail of insignificance that manuscripts of a universal history extensively glossed by Perizonius were found among the volumes in Thomas Jefferson’s personal library (now at the Library of Congress) at the time of his passing. The manuscript’s original author was the sixteenth-century Italian Jesuit historian Orazio Tursellini or Horatius Tursellinus, who lived a hundred years before Perizonius. His Epitome of universal history spanned from the Book of Genesis to the 1500s. Perizonius was not just a classist, he taught universal history extensively, primarily using the Tursellinus Epitome and his own extensive commentary as the notes he lectured from. An academic paper from 2017 which examined Perizonius’ Epitome commentary found that he “could command geographies and temporalities far distant from Greco-Roman antiquity.” Perizonius had the erudition and knowledge of the classics associated with the ancients, however much of his scholarship resembled the empiricism of the moderns. But most notably, his via media helped not only expand on a conception of universal history, but allowed him to walk a moderate middle road between his polarized colleagues in the ancient and modern camps.

The secularization of world history was an incomplete and unintended consequence of the Enlightenment.

It was during this period that a new definition of society began to be adopted. The quarrel of the Ancients and Moderns, was a battle over the type of world humanity was engaged in building. The New Science was seen as a way to steer the course and transform the conditions of civilization not by royal decree but by social movement.

The culture wars, as they became known in the late 20th century, have been ever present throughout modernity. It would seem they have their origins, at least as far as the modern period goes, in the wake of the scientific revolution, at the dawn of the enlightenment. Although the nature of early modern culture wars, battles, and quarelles, and our understanding of them changed over time, there does remain a cohesive thread linking them to each other and to subsequent culture wars of the 20th and 21st centuries.

However, it should be understood that the culture wars themselves are an extension of an even larger timeless struggle which stretches back to antiquity. Western man has always argued over the nature of progress and the process of civilization – including whether or not civilization is a good thing. Some of it has been constructive criticism leading to innovation, some of it has been useless speculation leading to confusion, division and much worse. All of it has been argued over for centuries and continues to be.

A final thought to be expanded on in a future essay: Not only were the early 18th century battles between the ancients and the moderns the first real culture wars of the modern period, they were the catalyst for the enlightenment movement they culminated into – A movement which shaped the condition of modernity.

Thanks for reading. For more from this author, read Antisemitism is Surging in the West

Follow Woke Watch Canada on X - @WokeWatchCanada

Or, by contributing to our Donor Box:

See footnote one.

Dupre (2004) pg 4

Edelstein (2010) pg 2

See footnote one.

See footnote one.

Really well researched look at how the gloss and lemma tradition set up the ancients vs moderns debate. Perizonius's via media approach is super relevant today cause we're still kinda stuck in that binary thinking between empirical novelty and erudite tradtion. The parallel to Augustan Rome's collapse is wild tho, makes me wonder if we actualy escaped that cycle or just delayed it.

The writing is sublime: “…the credulity to locate patterns of truth as they cast vague impressions in fleeting shadows flickering under dim and distant lampposts on ghostly walkways long vacant of the hustle of life.”

The indigenous debate may also be a culture war, ancient wisdom and notions of truth versus modern reexamination of our society by habitual skeptics.