Canadian History Through Heraldry

Exploring the Right Honourable Stephen J. Harper’s Flags of Canada

Woke Watch Canada is a reader-supported publication. Please consider becoming a paying subscriber or making a one-time or recurring donation to show your support.

By

In the Middle Ages a new practice emerged out of the need for knights to identify themselves during battle. Armour made them unrecognizable as it evolved to cover more of their heads and bodies. How were knights to know who the enemy was if everyone was similarly cloaked in coifs, great helms and chain mail? The solution was to emblazon their shields with distinctive markings. One of the oldest artifacts to document this is the Bayeux Tapestry – which is not a tapestry at all, but an embroidery of the conquest of England (1066).

The Bayeux Tapestry is an extant example of proto-heraldry. Because of the low significance of the images depicted on the knight’s shields, the heraldic bar was not quite met. True heraldry must serve a greater function than mere identification, it must be meaningful, heritable and employ a systemic approach. Blazon, the language of heraldry, “a specialized jargon rooted in Norman English,”1 had not been formalized in the eleventh century when William, the seventh Duke of Normandy, became England's conqueror.

While the very first authentic item of heraldry is not known, an early example which met the orthodox requirements can be found less than a century after William. Upon becoming a knight, the Count of Anjou, Geoffrey Plantagenet, received a shield from his father-in-law, King Henry I of England. Described in blazon as "a blue shield with golden lions rampant," this coat of arms is a good candidate to be considered among the first instances of proper heraldry from the medieval period. It marks the beginning of the long standing heraldic traditions of Western Europe, that would later be transplanted to the New World.

The methodology of heraldry was just beginning to take shape by King Henry’s time, as demonstrated in the design of Geoffrey Plantagenet’s shield. The colour of the field (background colour) and the charge (symbol or object in the shield) were heritable traits. The background was blue, and the charge was gold. This was consistent with an important heraldic convention called the tincture rule: colours were not to be placed on colours, and metals were not to be placed on metals. Golden lions in rampant posture (standing on hind legs with extended claws and tongue), to denote strength and nobility, were illustrated on a blue background. These design elements persisted for centuries within the Plantagenet’s lineage.

The Crusades were a critical period during which much of the syntax of heraldry was developed. It was this period when heraldic symbols began to appear not just on shields, but on banners and flags as well. At first, similar to the practical considerations for adorning shields with marks of distinction, flags were illustrated with a knight's personal coat of arms. By the Third Crusade (1189–1192), nobles were known to employ standardized heraldic symbols. Richard the Lionheart, for example, used three lions passant guardant (walking with head turned to full face) illustrated in gold over a red background, to symbolically project both majesty and guardianship.

Although flags and banners had been in use since the medieval period, a formal discipline was not developed until the mid-twentieth century. Vexillology is the study of the history and symbolism of flags; and Vexillography refers to their design. Vexillology separated the study of flags from the larger subject of heraldry. The term was coined by the American flag scholar Whitney Smith, who founded the Flag Research Center in 1961. Smith is also credited with designing the “Golden Arrowhead,” the national flag of Guyana.

Canada was the first nation to adopt a national flag with design principles influenced by the then new discipline of vexillography. Just a few weeks ago, Former Prime Minister Stephen Harper, who was himself an amateur vexillologist in childhood, published a book called Flags of Canada, which examines the flag history of Canada and the former French and British colonies. The book includes just under 50 beautiful flag illustrations in colour by artist Greg Stoicoiu (who is legally blind!).

The following will discuss some of the content in the book. All quoted lines are the written words of the Right Honourable Stephen J. Harper, as I plucked them from the pages of Flags of Canada.

Beginning with the flags of New France, Harper sets the scene by explaining that the French viceroyalty in the New World was “much larger than Canada today: it included the Ohio, Missouri, and Mississippi valleys, all the way to the Gulf of Mexico.” Describing it as a “paper giant,” with French claims “contested by the British from the outset,” he expounds on its “doom” made apparent “with the British population in North America outnumbering the French by over twenty to one.”

New France, with its origin in the first voyage of Jaques Cartier in 1534, ceded its territory to the British in 1763 with the signing of the Treaty of Paris at the end of the brutal Seven Years’ War, essentially relinquishing control of mainland Canada. French heritage would live on in Canada’s heraldic traditions, supported by the francophone population in Quebec which “remained largely intact.”

The Kingdom of France did not have a specific official flag during the period of New France — a single flag assigned preeminent status is a modern practice associated with nations, while Kingdoms typically used dozens of different flags for various official purposes. However, the official Canadian position at the time (which in all likelihood is incorrect) was that France’s primary flag was the Banniere de France — three gold fleurs-de-lis (symbolizing the Holy Trinity) on a Royal Blue background. Because of this belief, the Banniere de France found its way, depicted as being held by a unicorn, onto the Canadian Coat of Arms when it was first approved by an order in council in 1921.

Historians now know that “inhabitants of New France clearly identified white as their national colour.” The uniforms of the French infantry were white, and merchantmen were apt to use the French naval ensign, the Pavillon blanc, which was a plain white flag with no markings at all. Visually the same as the universal flag of truce, the Pavillon blanc “is traced from the Middle Ages, including from the white banner used by Joan of Arc, which also sported gold fleurs-de-lis and religious symbols.”

The lack of distinguishable French symbols presented an obvious problem that was overcome, at least for official purposes, by the addition of the royal shield – gold fleur-de-lis on blue background – for a flag named the Pavillon blanc aux armes. This flag, “probably the closest thing to a flag of New France,” was used on at least two occasions. “Its use of the royal shield and the dominant white colour were the two clearest symbolic manifestations of French authority and identity in North America.”

The British parallel to the Pavillon blanc aux armes was the Red Ensign – “Both types of flags were based on the dominant maritime ensign, in the predominant national colour, and sported national symbolism.”

At the end of the 19th century Canadians had entered into the first of four “full fledged flag debates.” The contentious question concerned what would be Canada’s national flag. By the time of confederation, Canada had primarily used the British Union Jack, and secondarily the Canadian Red Ensign (A red ensign with the addition of the Canadian coat of arms).

Calls for a unique flag which would reflect Canadian identity grew louder at the turn of the twentieth century. In 1925 Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King created a committee to deal with the issue of a national flag. However, this effort failed to produce results and faded away without a solution. Subsequently, in 1946, another Parliamentary committee advocated for a modified Red Ensign design with a gold maple leaf. But it did not inspire many Canadians and eventually disappeared to history’s dustbin.

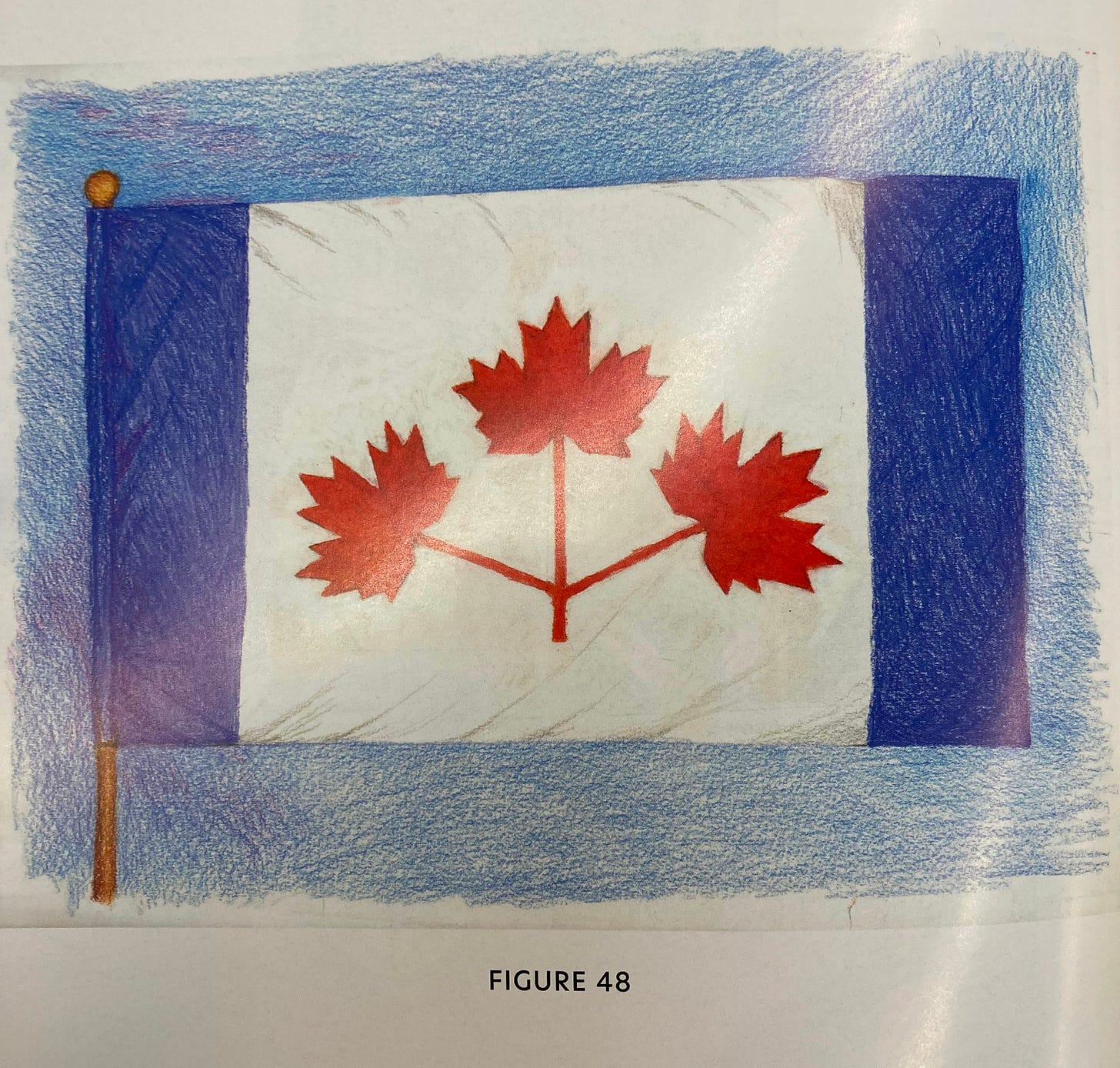

The Suez Crisis of 1956 added an unexpected dimension to Canada’s flag debate. Egypt had refused diplomatic efforts by Canadian peacekeepers due to their use of the Red Ensign (because it included a Union Jack). In 1964, Canada entered what is known as the “Great Flag Debate.” In June of that year, Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson brought a resolution to the House of Commons with the purpose of adopting a new national flag. Pearson’s favorite design, referred to as the Pearson Pennant, sported three red maple leaves on a white background abutted on the outer left and right sides with blue bars (which symbolized Canada’s sea to sea geography). In Pearson’s view, a new national flag should not include a Union Jack (like the Red Ensign) in order to better reflect the independence of Canada (and to not alienate French Canadians who did not have the same attachments to British heraldry).

Opposition leader at the time John Diefenbaker aggressively defended the Red Ensign. He claimed that Pearson was erasing Canada’s colonial past and demanded a referendum to decide the matter. With the flag debate showing no signs of reaching a resolution, Pearson assigned a 15-member all party committee to reach a consensus. The committee received over 3,500 designs from the public. Three candidates were chosen as finalists: the Pearson Pennant, a Red Ensign variant, and a solo maple leaf design by historian George Stanley, Dean of Arts at the Royal Military College in Kingston.

On October 22, 1964, in a unanimous decision, the committee chose Stanley’s flag. The artist Jacques Saint-Cyr added the finishing touch by modifying the design to reflect an 11-point maple leaf. Then, after it had been returned to Parliament, on December 15th at 2:15 a.m., Stanley’s Maple Leaf flag passed 163 to 78. Approved by the Senate two days later, with royal proclamation signed by Queen Elizabeth II on January 28, 1965, the Maple Leaf flag became Canada’s official national flag. The Red Ensign was officially lowered and the new flag raised on Parliament Hill for the first time on February 15, 1965. The Maple Leaf flag has been Canada’s preeminent national banner ever since.

The heraldic significance of the Maple Leaf flag is clear. The two founding nations — Britain and France — are represented with the colours red and white. The red bars at the left and right edges, represent the two seas Canada is sandwiched between. And the leaf of the sugar maple is an all-Canadian symbol considering this particular species of tree is native to Canada and had not been planted outside of North America until the 18th century. To be honest, I am partial to the Canadian Red Ensign, but I was born way too late to weigh in on that debate.

Prime Minister Harper’s Flags of Canada is a short book that can be read in a few hours. Even so, it is chock full of history. It has inspired me to teach what I now call history through heraldry to my kids (everything I do must have a snappy catch phrase). Flags of Canada has become assigned reading in my house! I highly recommend this enriching addition to Canada’s historical literature to both adults and kids — for the great story told through Canada’s heraldic traditions, and for the beautiful illustrations that bring it to life.

Thanks for reading. For more from this author read, Canadians and our ties to Americans

Follow Woke Watch Canada on X - @WokeWatchCanada

Or, by contributing to our Donor Box:

Harper, Stephen Flags of Canada (pg7)

Also the final flag selected by that committee before the final three was identical to Stanley’s single red leaf but had blue borders like the Pearson Pennant only a darker blue and in the dimensions we see with our current red borders. The intention: a red maple leaf from sea-to-sea. It was set aside because of Quebec reps suggesting that blue was a Quebec colour. Thus the final three were chosen to compete instead. This I have on the good authority of the senior civil servant in that committee.

You might think this history is interesting as well. Tattooing was in the lands called Canada before European cultural influences.

https://open.substack.com/pub/soberchristiangentlemanpodcast/p/the-hidden-history-of-tattoos-essay?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=31s3eo