Psychology: My Non-Woke Personal Library and Its Saving Virtues

An Essay Series for Readers - Part Three

Woke Watch Canada is a reader-supported publication. Please consider becoming a paying subscriber or making a one-time or recurring donation to show your support.

(For new readers: Welcome! This series is for serious readers and lovers of Great Books and the Great Ideas found in them. Please start at Part 1. And here is Part 2)

Psychology: My Non-Woke Personal Library and Its Saving Virtues - Part Three

By Geoffrey Clarfield

When I look back at my parents’ generation, men and women born in the Americas just after WWI, I feel I can make the admittedly sweeping generalization that most of them did not have an inner voice. The field of interpersonal or depth psychology was in its infancy, and it was a factional one at that. The now widespread idea that we all have an unconscious, that we are ruled by powerful passions that are often not recognized, that they begin to operate in childhood and help form our adult characters, and that these passions are often culture and context specific, and on top of this idiosyncratic, is a generalized insight that did not emerge until the 1960s.

Often, after having made an error of judgement or a social faux pas, I ask myself, “How did I manage THAT one?!” This triggers an internal, after the fact exploration assisted by the likes of William James, Freud, and the purveyors of cognitive science alongside the discoverers of ADHD and Shadow Syndromes in all their changeable diversity. So yes, I have a few shelves of books on psychology. But this was not a neutral venture that came from natural curiosity. It was a reaction to psychiatric malpractice.

Simply put, when the mid-1960s came crashing into our household my dear departed parents were unable to understand how it was that their sensitive, curious, musically talented son, might not choose to live like them, as had become increasingly apparent by my mid-teens.

My father turned to a psychiatrist, a man his own age who was a war veteran like himself, with whom he was working on managing his chronic hearing due to his experience as an artillery officer in Halifax harbor during WWII.

So when I was 15 years old, I was whisked off to the office of this elderly man once a week and given a whole bunch of incoherent adult psychology books to read that were written by a breakaway of a breakaway student of Freud who had made it to New York before the war. I was told not to tell anyone that I was in therapy, which of course made me feel inadequate and ashamed.

The therapist asked me to write out and discuss my dreams, hopes and fears. He had a simple way of categorizing dreams: they were either normal or neurotic. In my case, I had the usual anxieties of a developing teenager, so in addition to having him go through my dreams like a Catholic Priest during confession, he would often intimidate me by saying that he would include my revelations (without my permission, of course) in the book that he was writing that, thankfully, was never finished or published.

Apart from unethically treating many other members of my family and my extended family, he also judged family disputes. He was childless and turned psychotherapy into a series of mental torments that branded mostly “normal” people “incurable neurotics,” making us feel abnormal, damned for life and without hope. He certainly did his best to make me feel that I was an “incurable neurotic,” damned for life.

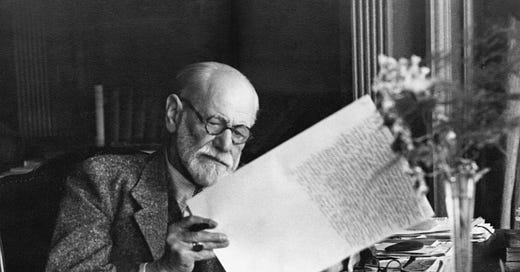

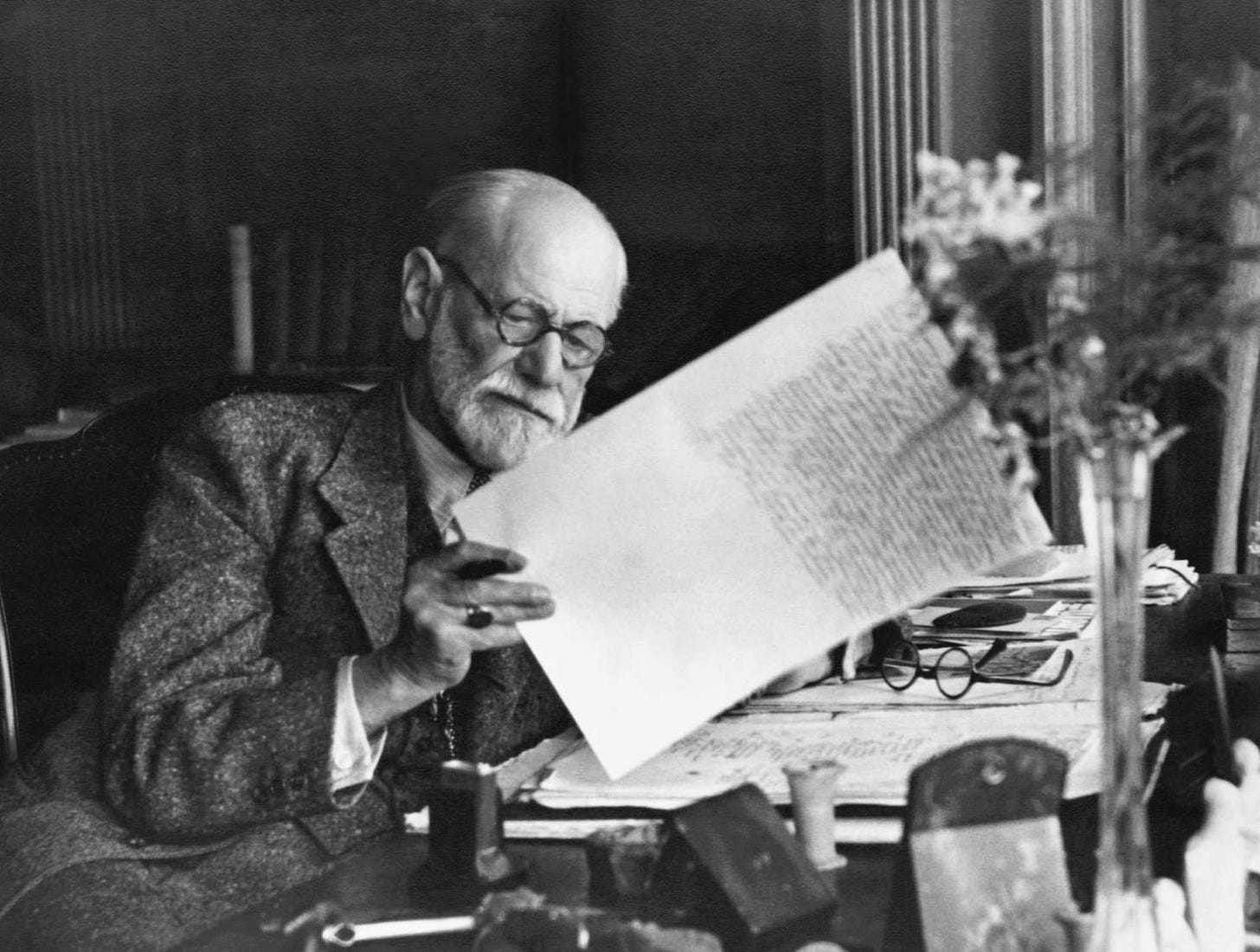

One of his basic rules was that “You should not read Freud.” So, of course, I did. It was while I was being psychiatrically misdiagnosed and mistreated, that I started reading outside of the box, starting with lots of Freud: The Interpretation of Dreams; Civilization and Its Discontents; the Future of an Illusion; Totem and Taboo Moses, and Monotheism; The Psychopathology of Daily Life, as well as biographies of Freud by the likes of Peter Gay and others. When I encountered Adler’s Great Books, I was glad that he chose Freud over Jung. Even though Jung is far more popular now, despite my encounter with a bad pseudo Freudian, I prefer Freud, who I think has been much misrepresented. (No, he did not believe that all our problems are about sex).

Over the years I have also read and kept some introductory textbooks and histories of Western psychology on my shelves. From them I have drawn the following conclusions. Aristotle was not wrong about the three kinds of soul, and Freud’s distinction between id, ego, and superego is quite similar. Victor Frankl was not wrong when he argued that without a search for meaning, life does not feel whole. Maslow’s hierarchy of values also feels right.

Everyone is now aware that men and women fantasize and visualize, and that while we live in a competitive society and must strive for excellence, we also need to be thankful for what we have. The Yogis and Buddhists are correct to teach us mindfulness and presentness so that our tendency to defer gratification does not become an end in itself. Even today’s born-again Christians preach a theology of thanksgiving. I confess that I have not been above reading twenty to thirty books on popular psychology with titles like: Games People Play, Passages, Emotional Intelligence, Focus, The Seven Habits of Effective People, Getting to Yes, etc.

Some years back, using Google Search as an oracle, I typed the following query, “Why am I so damned sensitive?” The search gave me Elaine Aron’s site on books about highly sensitive people (HSP’s.) She starts her books and web site with a short list of questions. If you answer all of them in the affirmative, as I did, you are an HSP. It turns out that this is an inborn physiological temperament.

Now that I know that I have one, it has been an enormous relief. Until recently, because of psychiatric malpractice, I still characterized many inborn traits of mine as “neurotic.” Four cheers and many thanks to those popular psychologists. I do know that these “popular” books and theories have made me more self-aware, but I am told that this has not changed my basic nature and my hidden —and not so hidden— idiosyncrasies. Somewhere down the line I did read books that said, “Strive for change but remember wherever you go, there you are.”

So if you explore my library, you will see that the complete works of Freud are still there (hard cover with light blue paper books covers, most of them at least) along with a number of biographies, introductions to Freudian psychology and a few good books on Freud and anthropology. For Freud made certain basic arguments that inform most of modern psychology and American cultural anthropology. Some of his books are part of the Great Books canon. Here are just a few of his key insights.

We are all born with a nature, a temperament, and until we are fully adult, we have a tendency towards magical and wishful thinking, imagining. Our temperament is pushed and pulled by growing up with specific parents and siblings (Freud’s “family romance”). We have early, complex, sexually tinged longings. We often project our desires onto other people. We are easily traumatized and scarred psychologically. No family is perfect. No parents are perfect. We want our mother’s unconditional love and our father’s blessing and endorsement. We dream every night and these dreams are meaningful. We can be ambivalent about many people and things. We often displace our problems and believe they are something else or caused by someone else.

We can easily regress into magical thinking under stress. We tend to blame others, and scapegoat others when this happens. As adults we can regress to less mature versions of ourselves when stressed. If left to their own devices, children would murder, steal, and lie when angry.

So civilization requires that adults give up much of their libido and aggression. Doing so gives us so much neurosis. Becoming an adult is learning to work, learning to channel our passions and integrate our various personas without losing the child’s ability to create and fantasize, and to love what is near and accessible. I could go on, but it is mostly there in the literature.

Finally, Freud, as a secular Jewish thinker, wrote an essay called Moses and Monotheism where he argued that Moses was an Egyptian Prince who was influenced by the monotheism of the heretic pharaoh, Akhenaten, and that it was because he revolted against Egyptian Polytheism that he led the Hebrew slaves back to the Promised Land.

The Bible’s description of backsliding over the following centuries makes perfect sense if we accept Freud’s understanding that a populist monotheism did not happen easily or quickly, it evolved slowly over time, after many setbacks. Freud argues that the “evolution of monotheism” is one of the pillars of the West. Most Biblical historians and archaeologists ignore this argument. None of my professors ever recommend that I read it.

It is interesting to note Freud was a great fan of Shakespeare’s plays but doubted that it was Shakespeare the actor who authored them. Similarly, the “Oxfordians” argue that Shakespeare was an actor and a front man for the Earl of Oxford who was the true author of his poetry and plays.

As much as we would like to think that a commoner (a Hebrew raised in or near Pharoah’s court) or a simple actor from Stratford, could gain the ability to lead and free a nation of slaves or have the genius expressed in those plays, a Freudian perspective suggests that civilizations, like individuals, do not necessarily tell or know the truth about their origins. (On a strange, related note, I still cannot subjectively integrate that my paternal grandmother was born and raised in Vienna: the same Vienna where Sigmund Freud worked and studied, for it was never an accepted part of my family story/ lore, even though it may well be true).

I could go on about some of the choice psychology books on my shelf, such as The Natural History of the Mind by Gordon Rattray Tayor; or Steven Mithen’s The Prehistory of the Mind: The Cognitive Origins of Art, Religion and Science, his fabulous theory of the cognitive development of our species from australopithecine to modern human; or Hallpike’s Foundations of Primitive Thought, his magisterial book on primitive mentality; and Levy Bruhl’s earlier studies on this topic, How Natives Think, that gives us a paradigm to compare the thought processes of non-literate people with our own. But let me deal with these issues when we visit my anthropology shelf.

(Please read Part 4 of My Non-Woke Personal Library and Its Saving Virtues by Geoffrey Clarfield).

Thanks for reading. The next installment of this series deals with Psychology. For more from this author, read My Non-Woke Personal Library and Its Saving Virtues - Part One

Follow Woke Watch Canada on X - @WokeWatchCanada

Support Woke Watch Canada by upgrading to a paid membership:

Or, by contributing to our Donor Box:

Gotta say … I enjoyed this personal exposition of what this science is at a most basic and understandable level. I very much enjoyed reading your good writing and look forward to the next installment. TM

So much to praise here, such erudition, at times simple: “We often displace our problems and believe they are something else or caused by someone else.” My focus of late has been residential schools and how woke progressives are teaching the Indigenous to blame long-ago schools for current dysfunction in their communities.