Woke Watch Canada is a reader-supported publication. Please consider becoming a paying subscriber or making a one-time or recurring donation to show your support.

By

My conceit led me astray. I was mistaken. I am not, as I assumed I was, the pioneering innovator whose artifice concerning a rare literary approach involving the unapologetically blunt can be claimed to be original. It is not my invention, how laughable to ever think it was. No one, I suppose, has a monopoly on unabated directness. However, before I turn attention to a truly ground-breaking wielder of high-order frankness, it is first important to qualify this tool of the dead-eyed straight-shooter as one that holds no fat. For literary bluntness to evoke the devastating impact in which it is designed, it must not be deliberately mean-spirited, but it must be objectively true, substantiated by evidentiary means, grounded in sound logic, and on the side of a higher principle far more consequential than whatever particular detail might be argued over at any given point in time.

Mark Hecht has been doing literary bluntness much longer than I have. He has a way of doing it that I cannot help but admire. He is so casual about it. He is entirely matter-of-fact about it. He is stone-cold and utterly emotionless during passages where he so craftily deploys his almost understated use of it. Now that I think about it, I would distinguish my approach to literary bluntness as overstated. But since I have had the chance to really take in the Hecht style, I must admit that I find far more effective his unique, almost subtle, not quite soft approach to unceremonious plain-spokenness.

Later in this piece I will include some prime examples from Hecht’s new book of exactly what I’m talking about. But first, for readers who may be unfamiliar, Mark Hecht is a writer and former Geography professor who was cancelled from teaching and various other opportunities, just prior to the death of George Floyd and the period known as peak woke. It was 2019 and Hecht had the gall (or balls) to write a plain-speaking op-ed, which was published initially in the Vancouver Sun, that was critical of the authoritarian left’s interpretation of diversity. It provoked an immediate back-lash among a vocal minority of social justice warriors. This included charges of racism, whereupon the Sun’s editor-in-chief Harold Munro cowardly decided to pull Hecht’s piece and apologize for it.

Subsequently breaking from long-standing editorial tradition, Munro would not allow the publishing of any of the many letters the Sun received in support of Hecht’s free-speech rights. A not insignificant group of Sun readers found that Hecht’s views were not in the least racist. Indeed, it was an abhorrent affront to the open discourse one expects in a liberal society for the Sun to have removed and apologized for what was nothing more than a thought-provoking op-ed on a topic in much need of examination.

Turning to Mount Royal University, the same institution of higher learning that could not deal with the academic freedom of tenured professor Frances Widdowson (who is critical of Canadian indigenous politics). In the aftermath of his infamous Vancouver Sun op-ed, MRU also found intolerable Hecht’s inclination to think and express himself freely. I recently asked him if he would ever return to teaching geography. His response: “I really enjoyed teaching. Would I do it again? Probably. But not in a university. They're beyond hope now.”

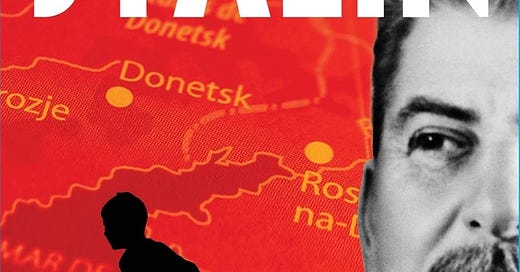

No matter which way you slice it, a good man (or woman) simply cannot be kept down. Both Widdowson and Hecht are made of a different sort of stuff than what is common to the precarious constitutions of the leftists social justice activists who colonize universities. It is easy to be a follower among a mob, it is another thing entirely to be a principled individual who stands against it. When MRU decided it no longer wished for Hecht to contribute to its geography department, Hecht found other ways to teach his lessons, tell his stories, and critique what he felt needed critiquing. Earlier this year, Hecht published a book containing many thought-provoking insights and invaluable life lessons called Running Away From Stalin: The Life & Times of Alfred Hecht, Phd, Dr. (h.c.).

As can be derived from the title, the book is about Alfred Hecht (Mark’s uncle) – who is a fascinating guy to say the least. Alfred was also a geography professor. A much-loved professor, who successfully ran the geography department at Wilfrid Laurier University for decades until the early 2000s. A good chunk of the book discusses Alfred’s approach to teaching geography, which involved international exchange programs with other universities, and lots of field work and day trips. For Alfred, sitting in classrooms, especially when one is studying the physical spaces found outside of them, was not the preferred mode for teaching geography. This in the field approach was/is shared by his nephew.

In the last section of the book, the changes to Wilfrid Laurier since Alfred’s retirement, and to higher education in general, are contrasted with the approach previously taken by Alfred and his colleagues who had created an advanced and much sought-after, collegial academic environment.

But this book was not just written for geography wonks. It is the life story of a brilliant, religious and highly principled man who contributed meaningfully and generously to Canadian society, and to the other places he had lived during his exceptional but fraught childhood. Alfred began his life in Russian controlled areas of Ukraine during World War II. He and his family went through a harrowing ordeal in their escape from the grips of Stalinist Russia. The first quarter of the book deals with their intense and agonizing flight to safety. In October of 1945, Alfred’s German-speaking Mennonite family, who had lived in a village over nine hundred kilometers away from Stalingrad (where the Germans lost the “bloodiest battle in history” in 1943), were forced to flee as the Red Army advanced to within a couple hundred kilometers.

German-speaking Mennonites inside Russian territories were already being apprehended by Russian authorities and shipped off to Siberia. Alfred’s mother, father, aunt, grandmother, and five siblings, along with whatever belongings they had space for, were loaded onto a horse and buggy and “joined the convoy of thousands who were heading West on dirt roads toward somewhere deeper inside the safety of Nazi Germany.” Not exactly the type of WWII story Westerners are accustomed to hearing. But indeed, for Alfred’s family, Stalinist Russia was by far the more dangerous place compared to Hitler’s Germany.

They initially ended up in German-controlled Poland. During the family's 10-month stay, Alfred’s father was drafted into the German army and was later killed in battle. The family once again was forced to flee the advancing Red Army. During their flight from Poland, Alfred’s older sister was separated from the family and lost. At a fork in the road, Suza and one of her friends had walked ahead of the convoy and waited for it at a small village. They soon realized they had gone the wrong way, the convoy was gone. Fortunately, they were able to find some help and ended up at an orphanage where they stayed until war's end. “Suza was lost but the family had to keep moving, hoping she wasn’t dead, hoping to be reunited with her later somehow, sometime. Now was not the time to stop.”

Six months later Alfred’s family learned that the Red Cross had picked up Suza and her friend. Alfred’s Mother and oldest brother took an enormous risk traveling one hundred kilometers by horse and wagon to an orphanage in Russian-controlled Czechoslovakia to reclaim her. Miraculously, they found her unharmed. The family was reunited.

“During the Great Trek out of Russia, through Poland, and into Germany, of the 35,000 Mennonites who originally departed only 11,000 were still alive in the West at the beginning of 1946.”

After the war, Alfred’s family would spend several years in a Mennonite colony in the Chaco region of Paraguay. There Alfred spent his formative years. They had wanted to go to Canada, but were stymied by a requirement that families must have a patriarch (who must pass a “rigid medical examination”). With Alfred’s father having been killed in the war, Canada was off the table. The next best option was South America. Paraguay, which already had a small and productive Mennonite community, was willing to take them unconditionally.

Eventually the family immigrated to Canada where they became citizens. In Canada, Alfred pursued higher education at the University of Manitoba. He completed his Phd in 1972 at Clark College in Worcester, Massachusetts, but then took a teaching position at Waterloo-Lutheran University – which would later be renamed Wilfrid Laurier University – in Ontario, Canada.

Alfred specialized in economic geography. He was interested in the little known Central Place Theory which was developed in 1933 by German geographer Walter Christaller “as a way to explain the spatial distribution” between small to mid-sized cities and large cities (economic centres).

“Christaller proposed that urban centres existed as ‘market centres’ and each market is related to the products it can offer and the distance its customers are willing to travel.”

Alfred began his masters thesis at the conclusion of the 1960s. He had a greenlight from the university to pursue the viability of Central Place Theory in Canada – specifically, the prairies. “His working hypothesis was that Portage La Prairie in western Manitoba was a ‘market centre’ that should align with Christaller’s Central Place Theory. To find out if this hypothesis was accurate he needed to do one major task – ask everyone in town where they shop.”

There is something about the way that geographers think, and write, that I find particularly unique. Hecht has no problem jumping around to different times and places. He does this often, seamlessly, while never confusing the chronological order of the narrative. In terms of physical spaces, the book shifts through many, and Hecht always sets the scene with concise but illustrative descriptors. Lines such as “the early afternoon had been warm although the leafless trees were barren and the buds were still absent any signs of spring,” help to transport the reader to Alfred’s back yard where one feels as though they are with Mark and Albert, sipping on a “Labatt low-alcohol beer on the back porch.” At other times Mark’s geographic sensibilities conjures up spatial imagery: “Anyone who has travelled across a large, flat, rural landscape such as the North American prairies, the Russian steppe or northern plains of Europe…”

Alfred’s father had been a teacher as well. This had much to do with Alfred’s pursuit of higher education. Quoted in the book is a line from a letter his father had sent to Alfred’s brother: “Everything you have you can lose but what you have in your head no one can take away from you.” This is made all the more profound when one considers that Alfred’s family did indeed lose everything they had, and relied on what they had in their heads to save them from losing their lives as well.

The last third of the book has a chapter called “Inside Laurier.” Up until this point, I had not detected much of the Hecht-style literary bluntness mentioned at the top of this essay. However, Hecht holds nothing back as he discusses the modern problems of universities. Alfred retired in 2006 with “auspiciously good timing,” as the real problems with universities manifested sometime around 2015. “Social forces seemed to suddenly appear at that time which were promoting the antithesis of what higher education was originally intended to be…that year was a pivot point when the internal rot of political correctness and cancel culture began to expose itself.” This was also the year of the infamous Lindsay Shepherd affair – Shepherd was a masters student and teaching assistant at Laurier who was histrionically accused by social justice fanatics of “creating a toxic climate for some students.” In fact, Shepherd had acted no different than what was traditionally expected of an academic in an academic environment.

“The Lindsay Shepherd affair became a poster child in Canada for what happens when the insidious destruction of political correctness infects an educational institution.” But Laurier was not the only university caught up in leftist social justice currents. “In a disturbing trend across the entire West, it appeared that universities were being ideologically undermined in a not too dissimilar fashion to that experienced in the East under Stalin, Hitler and Mao.”

At the time of Alfred’s retirement, he had been the chair of the geography department at Laurier. The current chair, Mary-Louise Byrne, replaced Alfred. “We had to put her in,” Alfred said. “Although it wasn’t a first pick, they wanted more women, you know.” Afterwards, according to Alfred, “everything went to hell.”

Like other institutions across the Western world, “academia was increasingly hiring the worst among men (non-masculine men) but for the most part, it was only hiring women…some argued that academia’s entire decline arrived on the heels of women.” Hecht suggests that the theory of male flight may have something to do with it. This theory “proposes that when a profession switches from predominantly male to predominantly female, at the 40/60 tipping point the profession suddenly experiences a rapid exodus of the remaining 40% of men.”

This makes a lot of sense to this writer. I see no reason why a man should stick around a feminized space where his language and behaviour will be constantly policed by resentful misandrists who think masculinity is toxic. No thanks. “The issue revolves around social status and there’s no way of getting around it. The theory of male flight argues that at a deep evolutionary level men compete with other men, not women, for intraspecies dominance. That’s a good thing. When men dominate a profession, their inherent competition with one another elevates and pushes innovation and excellence forward. Society in return, rewards them for that.”

And from the perspective of women, they “don’t have the same intraspecies competitive need for excellence, especially when challenging ideas. When women dominate a formerly male-dominated profession, innovation tends to vanish. So too vanishes the creation of new insights, technologies, ideas and the expansion of universal theories and laws.” See what I mean? There is no sugar-coating of anything from Mark Hecht. Did I mention I appreciate him for that?

I found there to be many similarities between Mark and Alfred. Curious about this, I asked Mark how much his uncle had influenced him. His response, “It's funny but my uncle, being on the other side of the country, who I saw sporadically, didn't influence my decision to go into geography nor the way I taught it. Yet, we certainly have similar ways of doing things and seeing the world. It must be in the Hecht DNA!” I wonder if there might be a general geographer's DNA at play as well, for both Mark and Alfred seem as if they were almost made for the purpose of studying terrestrial space. Geographers are a special breed, with unique ways of seeing and understanding the world. It’s a shame geography students no longer have access to Mark’s insights. However, he is not just someone with geographic DNA, he is a born educator with a masters touch at elucidating ideas. We may not have him in the classroom anymore, at least for now, but man can this geographer tell a story! Without a doubt, there is much to be learned from his writings. I plan, from this point forward, to read everything Mark Hecht publishes!

Thanks for reading. For more from this author, read When the West breaks your heart

Follow Woke Watch Canada on X - @WokeWatchCanada

Or, by contributing to our Donor Box:

I messed up on linking Mark's book to where it can be purchased. I have since corrected that and the link in the essay now directs to Mark's website. For convenience, here it is: https://markhecht.ca/where-to-buy/

Interesting, especially the characterizations of women/men dominated spaces.