In last Sunday’s post Critical Theory-Shmeory I discussed an informal research group that myself and Dr. Scott Miller (formerly Mr. M) started a couple of years ago. We call it Lighthouse Think Tank, because so far, the people contributing research have all met through the group Lighthouse.

For reference, here is a short blurb on Lighthouse:

Lighthouse was established to build a collaboration network for Canadians who are concerned about the use and enforcement of illiberal practices to address current social issues. Lighthouse network participants believe in the principles of a free liberal society which seeks to achieve justice while upholding the foundational freedoms and values of our society

Much of this is not new to regular Woke Watch Canada readers, however, Scott was away for several months defending his doctoral thesis. Understandably, this had him quite tied up. I kept in touch with him the entire time, as he kept me abreast of the details of the essay we present to you today.

During Scott’s absence the lights had gone temporarily dim in the Lighthouse Think Tank research laboratory, and a few cobwebs formed in the corners. But we have since swept the floors, dusted the bookshelves, cleared the cobwebs and changed the lightbulbs. In other words, Scott Miller is back, and so is Lighthouse Think Tank.

The essay we present today, researched and written by Scott Miller, is so much more than the mere publishing of an essay. Even though this is a remarkable essay on its own. However, what today marks is a milestone for myself, Scott and others involved with Lighthouse and Woke Watch Canada. This essay is a milestone marking an important achievement that fits into a larger movement.

Woke Watch Canada is not a stand alone newsletter. Not by a long shot. We are nothing short of an invaluable hub of the counter-woke resistance. We are strategically aligned with others who share our values and counter- woke resistance aims. But we are resourceful enough to take matters into our own hands, when the situation calls for it.

In the age of woke, a terrible crisis in both knowledge production (universities) and public sense-making (media) has occurred. This makes it extremely difficult for citizens to understand what is going on in their society. Making it difficult to organize counter-woke resistance.

There is a problem with knowledge production in the West, this presents the need for independent truth-seeking scholars to produce knowledge outside of institutions. With no research funding we have taken it upon ourselves to create our own little research institute.

If Lighthouse Think Tank is our “university” that produces knowledge, then Woke Watch Canada is our media organ that helps readers make sense of it.

We are considering Scott’s excellent essay to be the first academic paper to be published by the Lighthouse Think Tank. Before we get into the essays, a brief bio of Scott Miller:

Dr. Scott Miller has academic training in the study of history, and he holds that the history of ideas and idea systems has a special relevance to the culture war: through this endeavor, we come to know how and why an opponent comes to a radical position. By studying how the pieces fit together, we learn how to take them apart. Anyone able to access academic literature and to spend time working out radical jargon can figure this sort of thing out — the radical’s penchant for extolling and affirming their own methods is perhaps even more pronounced now that they have produced the dominant ideology. His research and writings for Woke Watch Canada and for the Lighthouse Think Tank have focused on this dominant ideology in Western society and on that aspect of it which is both indispensable and inconvenient for its defenders: its anti-liberal and utopian underpinnings.

Lastly, the following essay has over 120 footnotes. In fact, the footnotes almost contain within them a mini second essay. I implore the reader not to rob themselves of the richness of these detailed and expanded footnotes. However, the job of loading over 100 footnotes into the Substack manually one-at-a-time, is far too daunting. As a solution, please download the pdf (below) so you will have full footnote access.

At the very bottom on this post are some additional recommended writings by Dr. Scott Miller.

Enjoy the essay.

Fulcrum and Pivot: The New Left Remaking of Toronto School Policy

An Essay by Scott Miller

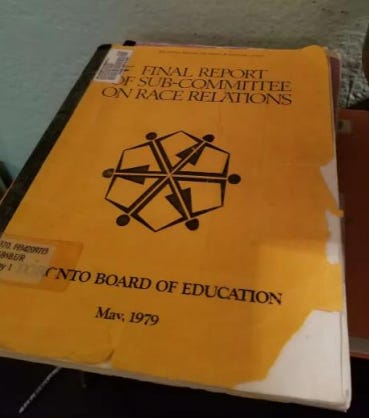

What does this essay attempt to explain? In 1979, the Final Report of the Committee on Race Relations was submitted to the Toronto Board of Education, the TBE (later, the TDSB as it will be referred to in this essay). The 119 recommendations of the committee were accepted in toto by the Board and would become the basis of race relations in Toronto schools, setting the trend for the rest of Canadian schools in the process. For insiders, the report and its policy impact was “an important stage in the struggle for equity” and “something tangible, something education activists could ‘wave around....’”

Why does this essay matter? In the following rather lengthy series of discussions, I have undertaken to produce a perspective on the development of radical education and practice that is something of an anomaly. I will present material with an insider’s access to education libraries, digitized newspapers of the era, and the memoirs of 70s radical education actors, now elderly and now saying some of the quiet parts out loud — just about every talking point in what follows is made possible by the data and descriptions provided by insiders. However, the anomaly comes in the fact that I will give you nothing of the obligatory affirmation of the once radical (now normalized) modes of reform and revolution that ubiquitously occur in the work of education theorists today. In fact, I am deeply sceptical. This essay matters because I provide the reader with an extensively documented commentary on the politics of the individuals and the groups that initiated the era of identity-based policy-making in Toronto schools. I will make the case that a knowledge of the politics—the system of ideas—that guide actors in policy-making is indispensable in assessing the merits (or lack thereof) of those policies and the claims that they make about society. In the policy programs submitted to the Board in the 70s and 80s that are of interest here, nothing is explicitly explained about the politics or the presuppositions of the people producing said policies; this information must be extracted from a variety of other sources.

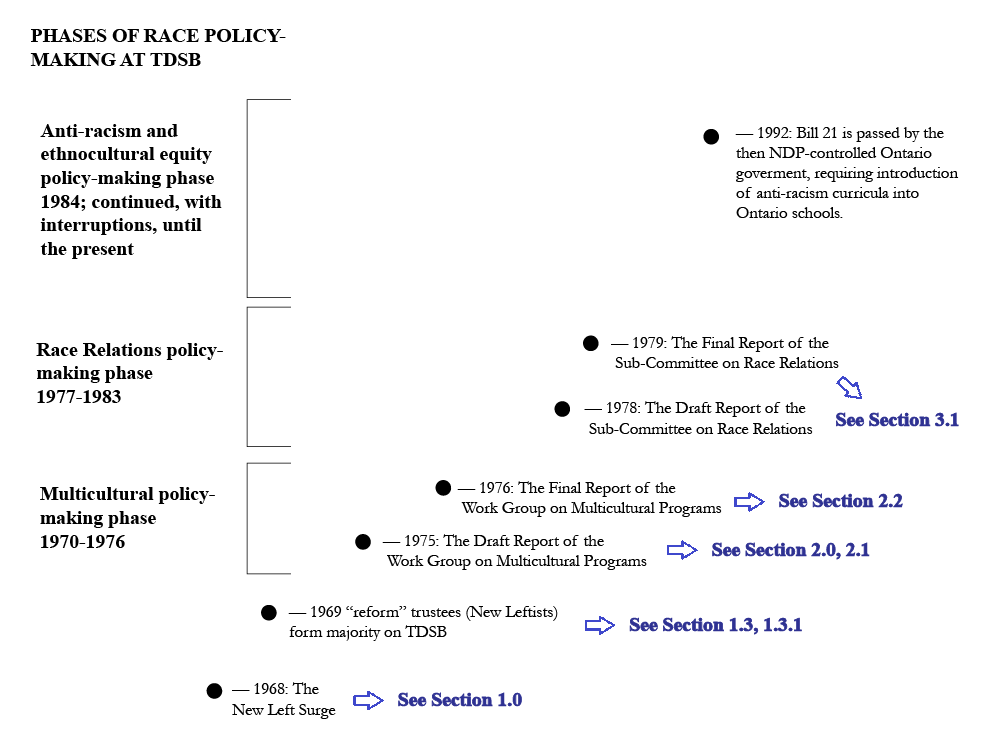

Figure 1: A Timeline of Race Policy-Making Phases at the TDSB, based on information found in the dissertation of Tateishi 2019. Intimations of the political leanings of the policy-makers are justified in the sections specified.

The radicals who initiated the policy reform phases sketched in figure 1 are, as we shall see, more profitably discussed as New Leftists. Their fundamental axiom, as with their counterparts today, was that liberalism was “not enough.” The reader committed enough to reach the end of this document will have gained insight into the following problems: What is the New Left, both on a global stage and on the level of local Toronto “reform” politics of the 70s? What idea systems and presuppositions, what sorts of radicalism, prefigured the anti-liberal (group interests rather than individual rights) policy-making in Toronto schools? How do initiatives such as community control of schools and the TDSB shift to ethnic community liaisons fit into the picture? How does all this set the stage for the anti-racism and equity policy incursion of the 80s, 90s and the present day?

In order to assess current 2024 TDSB policy rhetoric to the effect that “schooling in North America is inherently designed for the benefit of the dominant culture,” an examination of the history of policy ideas and the people who promulgate them brings with it the prospect of informed dissent. If one should choose to do so, contending with the root of a movement is to contend with the entire structure.

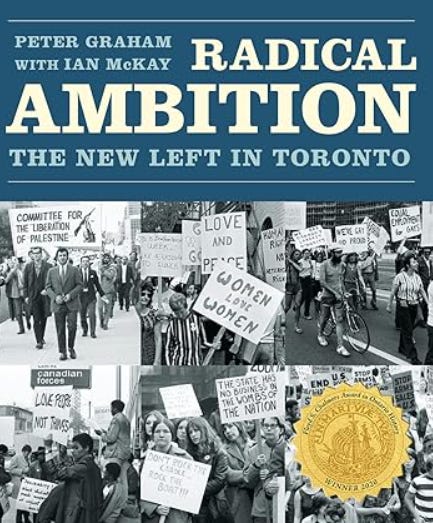

Figure 2: For readers who do not want to believe that left-of-liberal actors have been pushing buttons in Toronto policy-making for over 50 years, it is hoped that the cover of this book, written by Peter Graham in 2019, will intimate something: the claim that the New Left movement existed, it manifested in Toronto among other places, and that it carried out policy transformations according to the axiom “Liberalism is not enough,” is not as hard to document as it may seem.

Note: I had originally intended to preface my discussion with two examples of how radical activism can and has transformed education theory and practice: the first example addressed Critical Education Theory, the second had to do with the ongoing attainment gap between girls and boys (or how boys fell behind). These small discussions have now moved to appendix one and two, respectively.

1.0 The New Left put Abstractly: The phrase “New Left” should not call the moderate liberal party member to mind. Instead, it should evoke an approach to socio-politics that is fundamentally an adaptation of Marxist (Old Left) tactics, language and organization principles. This approach emerged on the global stage in the activist movements of 1968 and has never entirely gone away. From the entry “1968” in the Oxford Handbook of the History of Communism, one learns that such movements sprang up across the world in the 1960s in the context of combatting colonialism in the developing world, in free-market Western countries, and even in a few instances, in communist-controlled countries. These movements were not orchestrated by Moscow (which saw them as producing dangerous rival Marxisms) but seem to have developed organically as, across the globe, one disaffected group or another set itself against the establishment (colonial, capitalist or communist) and saw modified Marxian tactics as the way to conduct their program.

New Left activism became academically fashionable to left-wing American college students of the 1960s when leftist professors began pushing the following massively influential thinkers. Old Left thinkers were still part of the theoretical picture: Karl Marx (contributes “conflict theory” to sociology, one of the three primary focuses of that field); Antonio Gramsci (Italian Marxist who theorizes revolution as a process of subverting the institutions). New Left thinkers became even more influential: Michel Foucault (for decades, and still today, the most cited man in academia and the intellectual father of postmodernism); Stuart Hall (Marxist founder of “Culture Studies” which became the theoretical component pushed in journalist schools); Edward Said (Palestinian radical theorist and the intellectual father of postcolonial studies and the push to “decolonize” (everything)). There were many others of this sort. New Left college students of the 60s, upon graduation, would have a definite impact on educational theory and practice as many of them became the school teachers of the 70s.

The central tenants of the New Left system of ideas can be sketched as follows: like the classical Marxists (the Old Left), they aimed to carry out a utopian transformation of society “to be begun in the urgency of the here and now, and requiring collective rather than individual action.” Importantly, with the Old Left, they remained the staunch and intractable opponents of capitalism. Further, like all opponents of the Western program from Vladimir Lenin on, they are liable to declare themselves as “anti-imperialists.”

There were, however, major deviations between Old Left and New Left: the central axiom of the Old Left had always been the class struggle between the proletariat (the working class) and the bourgeoisie (the owners of production). While the New Left maintains solidarity with the working class, their central axiom pivots to the identity struggle — the women’s revolution, the ethnic revolution, gay activism and so on. It is still the case that both doctrines depend on dividing society into categories of oppressed and oppressors. Important for the discussion to follow, the New Left became critical of the centralizing and hierarchical tendencies of the Old Left, and they distinguished themselves by setting decentralization at the forefront of their policy-making. Decentralization became an effective tactic for opposing and undermining hierarchal establishments of all sorts, anything deemed the enemy of the revolution. This mode of operation became, as Breines describes it, a sort of “prefigurative politics,” that is, a political objective of developing “the seeds of liberation and the new society (prior to and in the process of revolution) through notions of participatory democracy grounded in counter-institutions; this meant building community”; this political objective was paired with a community organizing strategy committed to “building organization in order to achieve power so that structural changes in the political, economic and social orders might be achieved.”

1.1 The New Left in Praxis (applied in practice in the real world) — American Context: Since developments set in motion by the Students for a Democratic Society (hereafter, SDS) will foreshadow activist directions in Canada, the group must be briefly examined here. The touchstone for the application of New Left activism in the American context was the formation of the radical student group SDS in 1960. The socialist politics of the group are evident in the anti-capitalism of the Port Huron Statement (the founding manifesto of the group), which advocates for “revolutionary leadership” and states “we would replace power and personal uniqueness rooted in possession, privilege, or circumstance by power and uniqueness rooted in love, reflectiveness, reason, and creativity.” Prefiguring the community-based identity activism that is still a familiar aspect of the left today, SDS emphasized New Left style participatory democracy and claimed in its manifesto that politics are “the art of collectively creating an acceptable pattern of social relations,” that politics have the function of “bringing people out of isolation and into community,” and that politics “should provide outlets for the expression of personal grievance and aspiration.”

As a radical student movement, it isn’t surprising to see the SDS manifesto set its sights on the university. But there is more to this decision than is immediately obvious. They saw the university as a “potential base and agency in a movement of social change”; indeed, the university is “located in a permanent position of social influence”; it is “functionally tied to society in new ways, revealing new potentialities, new levers for change”; as an added bonus (for illiberal socialists), it is “the only mainstream institution that is open to participation by individuals of nearly any viewpoint”. The manifesto further adds that the New Left needs to start controversy in order to win and “the ideal university is a community of controversy, within itself and in its effects on communities beyond.” Further, the New Left should expect to obtain a “political synthesis” with the academic liberals of the left: “A new left must include liberals and socialists, the former for their relevance, the latter for their sense of thoroughgoing reforms in the system.”

SDS played a role in the advent of the “grievance studies” departments in the universities, most directly, Black Studies. In 1968, at San Francisco State University, the Black Student Union built on the momentum of the then raging black power movement and “demanded” that a department be created that would be controlled exclusively by people of color and that would accept all non-white student applicants regardless of academic qualifications. When this demand was rejected, the Black Student Union, in cooperation with SDS, coordinated a student and faculty strike at the university that would last for six months and would turn violent, requiring the occupation of campus by hundreds of San Francisco police officers for months on end. Striking students injured thirty-two officers during the strike, set hundreds of small fires and set off eight bombs and two firebombs. After this, black studies departments spread across the country in their hundreds, transmitting such identity-centric analyses as critical race theory and intersectional theory, and institutionalizing the radical claim that America is systemically racist.

According to the document America and the New Era produced by SDS in 1963, it is only through the curtailment of funding for the arms race that an egalitarian America society could be attained (surely, Soviet Russia would have seconded that motion); they say black Americans should come to the realization that the “demand for freedom” is a demand for a “new society” (safe to say, they mean a socialist society). The document calls for a “new insurgency,” that is, for organizers to go out into poor communities and be active generators of a variety of “political activities,” for example, to initiate organized protest and create “reform” political clubs for the poor. SDS initiatives such as ERAP (the economic research and action plan), which focused on issues of unemployment among the poor, have the veneer of charitable works, but to my eye, they are nakedly political. As insiders have documented, the political purpose of ERAP was to help put SDS in a position “to demand” (one supposes, through newly established community activist networks) “that resources be transferred from the cold war arms race to the creation of a decentralized, democratic, interracial welfare state at home.”

Because Canadian radical educators also followed the model of radical organizer Saul Alinsky, some description of his doctrines is necessary. Alinksy was a University of Chicago-trained sociologist whose ideology, I believe, could reasonably be called “New Left.” He wrote Reveille For Radicals (1946) and Rules for Radicals (1971), the latter became a sort of playbook for New Left activist strategy. Alinsky’s novel and massively influential approach to fighting “the system” entailed community networking in order to inflame local resentment and turn that into an action plan to divert power from above to below.

In Rules for Radicals, Alinsky sets about guiding the next generation of “radicals” on how to go about “revolution” and conduct “pragmatic attacks on the system” (p. xxiv). Alinsky entreats radicals to “work within the system” i.e. to not appear to be radicals to the common people because, in order to foment revolution in the community among the lower classes, they must be brought to accept “a passive, affirmative, non-challenging attitude toward change” (this phase is called “reform” p. xix-xx, compare SDS use of the same term above). In order to induce such a state, an organizer (of community-level activism) must induce disenchantment and discontent with the current system (p. xxii). Pushing ethics entirely to the side, Alinsky counsels radicals to consider only one thing about the means with which they pursue their objectives: will it work? (p. 24). Worth special highlight is the following dictum which Alinsky gives to his organizers-in-training:

"When those prominent in the status quo turn and label you an “agitator” they are completely correct, for that is, in one word, your function—to agitate to the point of conflict” (Alinsky 1971, 117).

Important to note here is that Alinsky doesn’t just mean that the agitator-organizer should antagonize his political opponents, although that is certainly a part of this playbook also; rather, Alinsky counsels his activists to get out into the community and to “rub raw the resentments of the people of the community, fan the latent hostilities of many of the people to the point of overt expression... an organizer must stir up dissatisfaction and discontent, provide a channel into which the people can angrily pour their frustrations” (Alinsky 1971, 114). And should an activist organizer select a minority group for this sort of motivating (manipulating, really), the fact that the target is a minority in number is no detriment: Alinsky held that it takes “the active support of no more than 5 percent of the population to mount an effective base from which to wield community power.”

1.2 The New Left in Praxis — Torontonian Context: New Left activism in Toronto emerges with the development of the Canadian equivalent of the American Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) student movement. As Churchill tells it, the stimulus for this development was an influx of disaffected migrant draft dodgers from the US, the founding of the Canadian Student Union for Peace Action (SUPA), which would become self-consciously New Left, and the establishment of organizational networks dedicated to anti-war effort, counter-culture and social justice; in turn, these preconditions led to “the formation, vibrancy and durability of movements for urban reform, alternate schooling and lesbian/gay liberation.”

The Toronto of the 1960s became a hub of New Left counter-culture activity. As Peter Graham, a historian of radical Torontonian politics, puts it, the New Left was in no way circumscribed to student movements: “New Leftism is frequently associated with student movements, but it actually set the pace for left-wing activism across the city. In sharp contrast to the centralized bureaucracy-laden governments of communists and social-democrats, New Leftists envisioned a decentralized society, operated largely by self-managed communities. Residents would design and control their neighbourhoods, tenants would manage their apartment buildings, parents, students and teachers would operate schools, and so on. Pedestrians and small-scale developments were favoured over automobiles, expressways, and other megaprojects formerly hailed as ideologically neutral symbols of a modern city. The socialist future would be postmodern.”

Much of this cannot be substantiated further here short of a mention in passing and documentation by way of footnotes. The New Left succeeded in radicalizing a significant group of students through the student group SUPA which formed itself on the American SDS model and there were other activist groups modeled on Alinsky’s community organization model; it succeeded in placing adherents on the Toronto city council (for instance, the so-called “reform caucus” city council group of 70s Toronto). On that note, it was not Justin Trudeau who first made a slogans to the effect of “diversity is our strength”, rather, this was the message of New Left mayoral candidates already in the 80s; The New Left succeeded in launching large scale municipal “reform” organization projects such as the ReforMetro group based on the participatory democracy / community outreach activism model; more relevant to our interests here, New Leftists launched the “alternative schools” movement and produced an identity politics revolution within the TDSB (discussed in section 1.3.1 below).

For the New Left political activist in the Toronto of the 70s, decentralization was the ticket to generating the means to revolution and it meant creating “a network of organizers, neighbourhood associations, community newspapers, and other activist bodies” to promote New Left thinking politicians like NDP member Jack Layton — whose message while running for Toronto’s city council is the encapsulation of the New Left movement: "Imagine a city which provides a home for all its citizens, which sees itself as an agent of social change; that is trying to end patriarchy and racism… imagine a city of activist neighbourhoods, tenant and resident councils, with many decisions being made locally through local health and neighbourhood councils... " As we will see below, for the New Left School Board member, decentralization means calls for the community control of schools, and the creation of an apparatus facilitating community control of schools.

1.2.1 The New Left, the Toronto District School Board, and Community Outreach Tactics: In 1969, the wave of New Left Board members and trustees that crashed on to the Toronto District School Board / the TDSB (then known as the Toronto Board of Education / the TBE) were frequently described as "progressives,” a term which serves no purpose other than to obfuscate the politics in play here. The press at the time described them as "blue denim radicals" and "firebrands" as being "distrustful of the system." All of these descriptors are vacuous and unsatisfactory. To get a better sense of what the New Left on the TDSB were really about, one might consider the word they use for themselves: “reformers.” While many may mistake this as a rather banal term, radicals believe that the real revolution must be preceded by a reform phase. What is more, Graham’s examination of the history of the New Left in Toronto places the “reformers”—both on Toronto city council and within the School Board—firmly within this system of ideas, so we are on solid ground in connecting the local “reform” politics of this period within the context of the greater New Left movement. Graham quotes one important “reform” trustee at TDSB, namely, George Martell (discussed further below), who wrote the following in the radical educationalist periodical “This Magazine is About Schools”: “As educational radicals if we are not practicing socialists, we shall be failures...”; the New Left need to “go into the cities and towns where most of us come from and organize block by block”; unlike over socialist movements, the New Left “must develop a very high level of control.” This is the essence of the New Left playbook in a few sentences.

One can also borrow an insight from an insider about what New Left “reform” TDSB members were reading at the time: they read “the political and economic ideas of Karl Marx"; they read “Ivan Illich, who proposed ‘deschooling’” — Illich, a Marx adjacent thinker who substitutes the “capitalist” for the word “industrialist”; they read “Saul Alinsky, the American organizer of low-income communities” — Alinsky, whose amoral strategies for community agitation were discussed above. With a reading list like that, small wonder that “many of the trustees elected in the political ferment of the late 1960s and early 1970s were activists who regarded the school system as an oppressive institution that needed to change.”

The election of numerous “reform” trustees onto the TDSB in 1969 seems to have been pre-empted by what appears to the present author to have been a probable subterfuge or hustle. As a result of the Fiona Nelson affair, a “reform” trustee, the Board was accused of wrongdoing and, following a blitz in the press, many “reform” trustees were elected to the Board in 1969 — they won control of the Board. After the elections were done in 1969, in all, thirteen of twenty-four trustees at TDSB were “reform” trustees, thus, they had a majority. The thirteen “reform” trustees of the “reform caucus” at this time (read: New Leftists or trustees agreeing to operate under the aegis of New Left policy-makers) included new trustees Fiona Nelson, Gordon Cressy, and Graham Scott (and 10 others); included in this number were long-term trustees joining the caucus such as Maurice Lister and Barry Lowes.

Other TDSB "reform" caucus members would arrive in the 70s: George Martell, Frank Nagle, Dan Leckie, Shiela Meagher, Doug Barr and others. Graham’s chronicle of the New Left in Toronto states here: “the 1974 School Board elections probably accelerated the degree and pace of change in Toronto education. This was when alumni from [the publications] Community Schools and This Magazine began to increasingly shape the Board. ‘We were very much a part of an international new left,’ one mid-decade trustee recalled. After the 1974 election and throughout the 1970s, the Board of Education was sometimes an audaciously left body.” Although I will continue to take pains to argue that “reform” policy-making is not something that dropped out of the ether but is New Left ideology applied to a real practice (praxis), it has to be observed at the same time that there was and remains no New Left political party in Canada. When it comes to political party affiliation, according to Gaskell and Levin, “most of the reformers” were associated with the NDP and a handful saw themselves as Liberal party members. Although the “reform” movement would fade in time (a change of trustees who vote NDP at the height of the New Left movement to trustees who vote NDP in the era of the legacy of the New Left movement), “reform” trustees were still active on the Board into the 80s: it was at this time that (current Toronto mayor) Olivia Chow, Fran Endicott and Pam McConnell and others carried on the “reform” tradition.

Having the majority (at least for a time), the “reform” trustees were able to impose their choice for high ranking Board members from amongst themselves: in 69, they selected Maurice Lister for chair, and Graham Scott for vice-chair; Fiona Nelson became chair of the Board in 1974, Gordon Cressy became chair in 1975, and Dan Leckie became chair in 1977. The succession of Nelson, Cressy and Leckie as chairs of the board meant that the New Leftists had a “formidable” lock on board practices in the 70s, and they had “close links with city hall, with Sewell.”

The rise of New Left TDSB caucus in 1969 was also pre-empted by the Trefann Court Mothers’ protest against the TDSB in 1968. Trefann Court is a slum in Toronto, and this is a good illustration of how the community organizers liked to work (these organizers worked in tandem with, or in some cases become, TDSB “reform” trustees). According to Shuttleworth, an insider, community organizers followed “the teachings of American activist Saul Alinsky” in order to use Ward 7 (which contains Trefann Court) as a “launching pad” for the “politics of polarization”; among these organizers was Gordon Cressy, future TDSB chair, who had actually travelled to the US to train in Alinsky’s community activism method. First, the organizers find common cause with the community, in this case, opposition to city-planned urban renewal in the area; the organizers (the agitators according to the Alinsky strategy) then convinced a group of five Trefann Court mothers that the system (the TDSB) was oppressing their under-achieving offspring; secondly, the five mothers themselves began to take “participatory democracy” seriously by protesting, speaking to the press, and, among other things, composing a petition to the TDSB entitled “Downtown Kids Aren’t Dumb.” However, although the document was presented as having been produced by the protesting mothers of Trefann Park, none of whom had an education higher than grade 10, consideration of the “erudite literary style” and the “presentation of data” made it readily apparent that the document had actually been composed by the organizers themselves. Unable to come to an arrangement from the TDSB that they were willing to accept, the Trefann Court mothers instead opt to have their children participate in the newly created Laneway alternative school, among the earliest of the alternative schools rolled out by the reformers, a New Leftist utopian social experiment. This community agitation paid dividends for the movement: not only did the New Left “reform trustees” take a domineering position in the decade to come, but, using the Trefann Court affair as a blueprint “the new board in Toronto in the early 1970s quickly set about involving more parents and community activists in committees, advisory groups, and community schools as part of their strategy to transform the system.”

The New Left movement (sometimes termed “the movement” among insiders) aimed for “community control” of education. In Toronto, this entailed organizers bringing “together parents and teachers to form the political action organization known as Citizens’ Committee for Change in Schools, as well as the Community School Workshop and the publication This Magazine Is About Schools. Their stated objective was “a shift of responsibility and authority from the hands of principals and senior Board administrators to the school community of teachers, parents, and students... Organizers from very advantaged backgrounds began to move into the slums of the Cabbagetown neighbourhood to begin to build their power base. It was not enough for school personnel to just be more involved with the community; they were required to cede control to parents and their organizers.”

When applied to education in Toronto, these strategies entailed two things:

i) Alternative schools (also known as “free schools”): The alternative school movement in North America, whether implicitly or explicitly, has taken its charter from the New Left position that “American liberalism was not enough, that the good society was one in which people shaped their own institutions to meet their own needs.” Ostensibly to provide an alternative to students having trouble in traditional public schools—but simultaneously, in my view, serving a clandestine political purpose—alternative schools were set up across Toronto in the 1970s; as insiders note, “alternative schooling was a key part of the new trustees’ reform agenda, and it was reinforced by a commitment to parent voice, local community building, and non-hierarchical power relations.” Alternative schools are not the focus of the current study, but the “reformers” pursued the creation of such schools to the utmost of their ability and produced Toronto’s SEED, ALPHA, and CONTACT alternative school initiatives, they established schools such as Laneway, Everdale, Superschool, and Point Blank; these schools were produced in consultation with, or by, the contributors to the radical New Left periodical This Magazine is About Schools.

ii) Community Outreach Workgroups: Writing in 1975, “reform” trustee Frank Nagle recounts that the reformers took to the creation of community outreach workgroups “composed of trustees and, at times, parents, teachers, community members, and staff” and that these workgroups helped to “short-circuited some of the normal response to professional staff opinion.” He further clarified that such tactics simultaneously reinvented the school board trustee: “previously, trustees were powerless to grapple with important curriculum and social service policies, which were left to administrative expertise. It is unquestionable that by fleshing out issues with community input trustees become power brokers in their own right... by listening, aiding, and responding to the community, some trustees disrupted the traditional reliance on the professional as expert.” By 1975, in Nagle’s estimation, some 2/3’s of TDSB had signed on to the “community” model (one supposes many would have had to have been unwitting or indifferent to the political dimension which was part and parcel of the entire community strategy), thus, fulfilling Nagle’s observation that “a group of trustees with radical tendencies not only serves to reinforce the positions and behavior of its individual members, but also can move an entire system.”

2.0 Work Groups, Committees and Reports: 1974–1976 — The Work Group on Multicultural Programs: Multiculturalism played a major role in the activist transformation of the conception of education in Canada. For those who aren’t particularly familiar with how multiculturalism developed in Canada, in sum, Canada had pivoted to a policy of “biculturalism” in the 60s in order to try and counter the Quebec nationalist movement (along with the Quebec separatists); numerous minority groups, most vocally and antagonistically the Ukrainian-Canadians, insisted that since bilingualism was being waved on, it would only be fair if Canada was remade as a place where every culture was celebrated (in practice: except that of the majority); and so, multiculturalism was demanded. When, subsequently, the government of Pierre Trudeau signalled its advocacy for “multiculturalism,” this did not a philosophy of social policy make; rather, the early days were the days of “song and dance” multiculturalism (when minorities, e.g. the Ukrainians, were bankrolled by the Canadian government to put together parade floats with cultural themes and so forth). The concept of multiculturalism soon travelled far and wide inside and outside of Canada, and New Leftists took it upon themselves to parse out what “multiculturalism” should mean for education theory; as we are about to see, the “reform” trustees at the TDSB would ensure that Toronto was no exception and set about producing both a “philosophy” and a policy of multicultural education.

Although the board had launched several precursors, of particular interest here is the Workgroup on Multicultural Programs which was inaugurated in May 1974 when “reformer” Gordon Cressy was the chair of the TDSB. The workgroup had begun under the moniker “the Advisory Committee on Philosophy and Programs of the New Canadian Population,” but this was soon changed to the name we are using here, the Work Group on Multicultural Programs. The work group produced three documents. The notion (evident in the work group’s original title) that a “philosophy” of multicultural policy could be produced led to the work group’s first document entitled The Bias of Culture (1974); on the basis of the arguments produced in this document, the work group then produced the Draft Report of the Work Group on Multicultural Programs (1975) and the Final Report of the Work Group on Multicultural Programs (1976) which made 99 recommendations to the TDSB — recommendations intending to reform TDSB’s allegedly deficient racial and cultural sensitivity practices.

What was the “philosophy” produced by the work group, and which trustees were associated with the group at the time “the Bias of Culture” was produced? There were six:

The ideological predispositions of the work group in 74 are consistent with what one may expect a group producing a radicalized education document to maintain: Leckie and Cressy were true New Left “reformers”; Lister was probably a different sort of animal, but he joined the “reform” caucus in 69 and was elected by the “reformers” to the position of chair; Meagher was a “reformer” and voted NDP, so a socialist of one or another stripe; it may seem startling that Atkinson was a conservative — what is there to say about the principles and integrity of a “conservative” who, part way through her life, discovers that she might as well have been a socialist all along? A memorial essay on her life published in The Star noted: “Atkinson, a Conservative, who later found her views aligned better with the NDP, campaigned for the Liberal Wynne many times because of their strong bond from those days.” The only wildcard is Ross, who the papers describe as an unpredictable “maverick” but who seems to have been a been a Liberal party member.

The central ideology of the workgroup is demonstrated only implicitly in the reports about to be examined; at no point do they declare “by the way, we make these recommendations because, in addition to X, Y and Z, they suit our New Left model of revolution.” It is hoped that the attention paid to politics in the preceding sections will help to render the implicit explicit.

—The Bias of Culture, a document produced in 1974 by The Work Group on Multicultural Programs, a TDSB affiliated work group.

2.1 Document 1 — The “philosophy” of the “Bias of Culture”: This document, which I will attempt to extract some essentials from in summary form, appears to have proceeded (one supposes) from discussions and deliberations of the six trustees who comprised the workgroup of 74 — there are no citations of authoritative positions, footnotes, often little in the way of justifications, a few statistics but “this paper intends to avoid overloading itself with statistical reporting.” The 48-page document begins by stating that there is a “problem” of educational opportunity development for immigrant people and that there is certainly a fundamental “cause” of this problem, and this cause has to do with ethnic communities and the cultural linguistic heritage which founded the schools in the first place. Although the nature of this “cause” is never clearly articulated in this document, they proceed to list what they see as the problematic effects for the current education of immigrant children in Canada.

Cultural Allegiance: for the radicals, the problem with “allegiance,” of course, is not that immigrants have cultural allegiance to their original country rather than their home country (Canada), it’s that Toronto schools are pumping out Canadian culture — and this isn’t conducive to immigrant’s ingrained cultural allegiance. P. 2-4: Immigrant students who come here, they say, will lose their “identity” when they run up against a culture in schools that is not their original culture — this will become a constant source of discouragement: “trapped between a life in which participation appears overwhelmingly impossible” and one in which is no longer valid (their original culture), the immigrant student’s life will be “amorphous and marginal.” Should the student choose to renounce their original culture, it is “not possible to overestimate the effects,” and if they go through with it, “in a very real sense, the young individual actually loses their parents,” they say. P. 8: Meanwhile, they say, because the child is learning Canadian culture at school, and English, the child becomes a “pedagogue” to their own parents—of course, this could only have horrible consequences—“[this] means that parents experience the ultimate humiliation of becoming their children’s children...” The Work Group’s flare for the dramatic would make even former drama school teacher Justin Trudeau blush!

And, in a moment of total cognitive dissonance, the Work Group on p. 21-22 complains that schools are disorientating immigrant communities: such communities, are “focused on the authority of the dominant male,” and “patriarchy is strong in the family configuration.” However, they say that because family structure has broken down in the West (thanks in no small part to the far left, actually) and the child is supposed to be more of his own decision maker now, immigrant families encountering modern Western models of family in the classroom find these new norms offputting or confusing. There you have it: the radical left’s endorsement of patriarchal proclivities here in Canada! (as long as it suits their current rhetorical purposes, and as long as they aren’t Canadian white male patriarchs). So much for “philosophy.”

The Ascription Question: the central problem addressed in the work is (what the Work Group presents as) the high number of immigrant students being streamed into undesirable vocational schools. The only set of statistics produced in the entire document presents data on this topic (p. 12). However, the problem is nuanced as the authors point out: if one goes by placement status (whether a student gets streamed in the low achieving vocational school), then i) the income of the parents is actually the bigger factor than whether it is an immigrant family or not — in fact, Canadian born native English speakers from low-income families were slightly more likely to be streamed than foreign-born students from low income families according to the chart provided on p. 12; ii) the trend of immigrant children born in Canada is to overcome the achievement gap whether their parents are low-income or not; iii) p. 12-13 the achievement problem is an issue mainly for immigrant students who had begun their education in a foreign country (but see point i again). Even the immigrant student population which is most affected by streaming is streamed to less desirable schools at a rate of (I would use the word “only”) 20.9%. Some might say “where is the problem here?” For the Work Group, it is presupposed that there is an unacceptable issue in these numbers and the only question is that of ascription, that is, what are Canadian schools doing wrong?

The West Indians, who are black, made up a significant portion of all Canadian immigrants by the mid-70s and they are of particular concern to the workgroup (p. 18). Even in the 70s, observers of West Indian immigrants in the US knew that they have “higher incomes, more education, higher occupational status, and proportionately far more business ownership” than African Americans born in the US; they are also roughly four times more likely to attend Harvard than are African Americans borne in the US. From this, one could actually draw two inferences: i) that the entire affirmative action policy machine is woefully misguided — the West Indian success shows that it was the work ethic and attitude toward education that was the bigger determinant in the 70s than were factors of skin color; and ii) taking the probability that what was true for America was probably extend to Canadian contexts as well, one can also infer from this information that the measures which the Work Group is going to propose are entirely unnecessary: immigrant West Indies blacks were (already in the 70s) outperforming locally born African Americans. Arguably, this was a result of the different culture that West Indies black immigrants brought to bear on life in America than did locally borne African Americans, and the West Indies immigrants, in point of fact, didn’t need special school programs to coddle that culture into paying dividends!

However, the Work Group will push forward with a New Left agenda to create community oversight of schools. It is of vital importance, they say, that the system learns about how the ethnic community “perceives its school.” P. 30 - To resolve what they represent as “issues” (the case of streaming being the only one substantially examined in this document) it is imperative to generate “healthy communication between the school and the ethnic communities they serve. This contention hardly needs testing.” They present the following identitarian counter-liberal stipulations about how the nature of such a communication should develop:

i) p. 32–33, whites need not apply: contact in the form of liaison work between schools of the Toronto system and ethnic communities depend heavily on the “ethnic social work,” i.e. if it is the black community, the middleman whom “the board employs precisely because s/he is of a specific ethnic origin, naturally function at the leading edge of school-community contact.” The workgroup is of the opinion that a white liaison would not have empathy from, or extent empathy to, the black community.

ii) p.33–34, whites need not apply: the workgroup finds that it “only makes complete sense” that ethnic teachers should be sought out for ethnic students, i.e. black hiring privileges, or, as they put it: “the education of the community rests in orienting employment practices toward ensuring that the school staffs reflect the ethnic make-up of the community itself.”

2.2 Document 3 — The Final Report of the Workgroup for Multicultural Relations (1976): Immigration policies had been adjusted in the 60s with the effect that more and more non-European immigrants made up Canada’s immigrant population (e.g., there was now significant immigration from the West Indies); concomitantly, the “multiculturalism” of the 70s became more about defining ethnicity on the basis of color differences and charting alleged manifestations of racism. In 1975, the Draft Report of the Work Group for Multicultural Relations was produced by the Work Group and it was sent around to the “communities” for their review and feedback; there is good reason to infer that when the Work Group states that it has consulted with “community groups,” black and native community groups carry the most salience here. This feedback, in turn, is represented as guiding many of the final recommendations appearing in the Final Report, recommendations that aim to reshape TDSB policy and modify curriculums (99 recommendations in total). In establishing this community feedback mechanism, the Work Group has put into practice (into praxis) key components of the New Left playbook: identity politics and community control of schools. Decentralization and the simultaneous emphasis on non-white community feedback enact the new formula of reform and revolution: the acquisition of power so that structural changes in the political, economic and social order might be achieved. The following summary highlights select recommendations.

• Multiculturalism to be built in curriculums: The final report acknowledges that there was a fundamental disagreement about whether it should really be the job of schools to contribute to the preservation of cultures which immigrants bring with them from around the world: p. 26 relates that when the Work Group asked the schools, the professional educators, about the matter, the general consensus was that it was “the community's responsibility rather than the schools." On the other hand, when the Work Group asked “the community” (by which they doubtlessly refer to the ethnic community), the answer was reportedly that the schools have a “responsibility” to contribute to the maintenance of their culture. “The community” further produced “demands for programs” that would play to their sense of “cultural and racial integrity” (p. 29). Here, one might recall the observation of Frank Nagle, reform trustee and sometime member of this Work Group, who observed: “Trustees themselves have short-circuited some of the normal response to professional staff opinion by developing a concept of consultation called the workgroup.” And so, inevitably, the Work Group is going to state that it “cannot agree” with the position of the professionals, ergo they issue the following sequence of recommendations which I paraphrase in plain English:

#31: Curricula should recognise the contributions made by various cultures and races; #32: school programs should be sensitive to the ethnic composition of each school community; #33: Canadian studies programs should generate understanding and respect for the cultural diversity of Canada; #34: A component of Canadian studies should consist of the local school community and cultural groups in that community; #35: the School Community Relations Department should assist teachers in the development of that material. #36: A curriculum review project be assembled to review all current curriculum material and establish what material is culturally or racially biased; #39: Curriculum and program planners seek the participation of “the community” (my quotes) in the development of cultural studies.

• Alleged Racism and Moral Purity Tests: After establishing that for the majority of people, “particularly white Canadians,” racism is buried deep in the unconscious, the Work Group states that one “community group” gave feedback to the Work Group that the eradication of racism should be the “primary goal of education.” As always, the Work Group plays cloak and dagger here, but the question of which “community group” that was won’t be a mystery to most readers. Page 37 states that there was another conflict of opinion between the ethnic communities and the professional educators, the teachers: the “ethnic organizers” recommended increasing the number of ethnic teachers to correct what they allege to be the wrongs of the system, while the professionals were “unanimously opposed to the use of any type of quota system.” Faced with this disagreement, the Work Group represents that the reasonable thing to do (if one reasons like a radical New Left Work Group) would be to “encourage applications” from individuals who demonstrate sensitivity to “the community” (read: the ethnic community). The Work Group further intends a sort of moral purity test, as will be seen in the following recommendations:

#44: Hiring practices for all teachers to explore the applicants’ sensitivity to “culturally diverse school populations,” and “willingness to communicate with parents in the local school communities” and “receptive personality”; #47: teachers who have demonstrated “a particular ability and interest in working with New Canadian [immigrant] families” should be encouraged to seek promotion to all levels of leadership in the Toronto system; 48: Applications for leadership positions should be “encouraged” from candidates who are able “to understand and respond to the community”; #51: a program should be developed to provide all staff with racial sensitivity training; #55: racial incidents at schools should become a focus for discussion and subsequent learning; #56: a program should be developed to integrate the issue of racism into the regular school program.

• The Work Group moves to perpetuate itself — The Creation of the School Community Relations Department (SCR) / The Creation of the Committee for Multiculturalism: The next set of recommendations (#58-#70) put forward by the Work Group have to do with the creation of a department at TDSB, the charter of which will be to function as a community liaison between the board and “the community” — essentially, it will drive the community control doctrine of the “reform” trustees but with a much bigger staff than the Work Group for Multicultural Programs and on a permanent basis. Regarding this set of policy recommendations, the Work Group relates on p. 43 of its final report that, upon consultation, dissent came neither from school professionals nor from the communities; an increase in communication between school and community seemed uncontroversial. Such a proposition will seem innocuous to most, certainly to most who do not perceive that community control of schools can be—and in this case, is—part of a clandestine political strategy. As Graham’s history of the New Left in Toronto succinctly observes, community councils were “crucial to the new left’s educational program.”

In a second strategy for self-perpetuation, the Work Group for Multicultural Relations calls, on page 40 of its final report, for the creation of a Committee for Multiculturalism to monitor and implement the 99 recommendations put forward in the final report. This newly formed committee would find that much of its mandate actually involves bridging the policy domain of race relations through the scope of multiculturalism and, for increased efficiency, the committee therefore called for the creation of the Sub-committee on Race Relations (SCRR) in 1977.

In the final section of the current essay, a brief consideration of these two legacies of the workgroup is presented.

3.0 Immediate Legacies of the Workgroup on Multicultural Programs — 1. The School Community Relations Department:

In the interests of brevity, I will attempt to approximate the character of the School Community Relations Department at TDSB by sketching a few of the important functionaries there: i) Marlene Green, from the black community, was among those hired by TDSB to work in the new department and she co-authored the department’s first report on race-relations. Her background in education was her founding and organizing of the community group called the “Black Education Project,” which saw itself as forming after “the rise of pan-Africanist black power”; with strong ties to the black liberation movement, this organization tutored black school children with a focus on “teaching African history” and “racial pride” — it’s school programs were run out of the UNIA hall in Toronto (the UNIA being a long running black nationalist association founded in the US). If it may help to bring these politics further into focus, the reader might note that the founder of the UNIA, Marcus Garvey, is thought to be ultimate source of the term “woke” — he popularized the exclamation “Wake up Africa!” among his 1930s era black nationalist followers, which eventually developed into “stay woke,” and finally “woke.” A historian of Torontonian left politics relates that the Black Education Project was set in motion by the group Black Youth Organization (BYO) which shared a common quandary with its sister organizations: should we attempt to transform society with a Marxist style revolution, or by imposing black identity as the paramount consideration in all things? (I paraphrase, but that’s really it in a nutshell).

It would be safe to conclude that Green was, ideologically, a black nationalist. One can get a sense of where this sort of “education” goes by considering the person of Lloyd McKell, a black community member who became the president of the School Community Relations Department in 1979; upon losing his job in 86, he would be rehired in various equity advising capacities and McKell would prove pivotal in bringing about Toronto’s first “Africentic” (black only) school.

Let’s not accuse the School Community Relations Department of not being diverse, however: it also hired people like Tim McCaskell, who is white. McCaskell is a gay man who, later in life, would be referred to as the “granddaddy of gay activism in Canada,”; prior to coming to the department in 83, he participated in “The Marxist Institute” (a far-left Toronto gay activist think tank founded in the 70s). He has remained a self-described Marxist. As for how a radical Marxist goes about trying to improve race relations, if you guessed “pompous struggle sessions,” you’d be correct! According to a fellow radical insider, McCaskell’s technique involved “shaming teachers and administrators,” and she noted “embarrassment, force and humiliation will not win friends.”

And just how sound is it exactly for education policy-makers to seek the knowledge of activist ethnic community members and to draw on their perceptions of how some ethnic children don’t take home the best results? According to one of the TDSB’s first black trustees, who had no problem acknowledging this for a rhetorical purpose other than mine, for “communities” outside the school “it's hard to put your finger on what the problem is, other than to say it's racism, because you're not in there and you can't figure out the blockages." Parenthetically, in 1986, elven years after its creation, the School Community Relations Department would be completely cleaned out, and all of its staff fired when conservative trustees got the upper hand at TDSB and decided the department was too “political.”

—The 1979 issued Final Report of the Sub-Committee on Race Relations, a TDSB affiliated committee.

3.1 Immediate legacies of the Work Group on Multicultural Programs — 2. The Sub-Committee on Race Relations:

Race policies in education went through three distinct phases in Ontario, beginning with the multiculturalist mode, moving to the realm of race relations and ending up with anti-racism and ethnocultural equity. What agitators prompted the onset of the race relations phase? It was certainly “reformers” following through with their strategies, for one. It was on the recommendation of the Committee for Multiculturalism that TDSB created the Sub-committee for Race Relations on March 16, 1977 with the mandate that the SCRR should make recommendations to the Board about how to “combat the spread of racism in Toronto.” More specifically, it was “with the encouragement of reform trustees Bob Spencer and Dan Leckie” [both consummate New Leftists] that the SCRR begin compiling a report about [alleged] Toronto school racism in 1977. Doug Barr, a New Left “reform” trustee since the early 70s acts as the early chairman of the SCRR. Spencer and Leckie were also “long time allies” of the Marlene Green’s Black Education Project, which I describe as black nationalist in character (section 3.0); it is stated in several sources that Marlene Green, who was active with the School Community Relations Department, “coauthored” the Final Report on Race Relations (although it isn’t clear to me in what capacity or to what extent this claim is astute). Additionally, the School Community Relations Department (section 3.0) itself impacted the recommendations produced by the SCRR since it “mobilized parents groups”—one presumes, only those belonging to certain demographics—“to bring forward their concerns.”

There was another major factor in the formation of the SCRR, that being pressure from a community group. Predictably, that would be the newly created TDSB Black Liaison Committee (an assembly of “parent and community activists” which the TDSB assembled to provide consultation in 77). The definition of “liaison committee” is given by insiders as follows: liaison committees were “informal committees promoted by reform trustees and made up of community members, usually from a specific ethnic community.” The probability that the Black Liaison Committee was essentially black nationalist is rather high since it also included black educators such Lloyd McKell (in section 3.0, it was noted that McKell became the force behind Toronto’s first Africentric school). Another member of the Black Liaison Committee was Dr. Fred Case who played a part in defining racism and issues of race for the committee and would later write the book “Racism and National Consciousness.” Predictably, a review of the book notes the “essentially Marxist” analysis of Case’s book, takes issue with its framing ( “minorities are (always) the good guys/innocent victims; the majorities are (always) the bad guys/evil oppressors), and describes Case’s take on Canadian teachers as follows: teachers are “alleged to exploit the disadvantaged and disinherited “races” they are paid to serve, in order to promote their own economic interests.”

Although TDSB committees had previously always been composed of Board trustees, The SCRR consisted of only four TDSB trustees—mainly, or possibly entirely, consisting of “reformers”—together with ten consultants: i) five from non-community groups (one from the Toronto Teachers Federation, the Secondary School Teacher’s Federation, the Elementary School Principal’s Association, the Ontario Human Rights Commission, the Toronto Board of Education’s Secondary School Students); ii) five from community groups (one from the Korean Education Society, the South Asian Origins Liaison Committee, the Black Liaison Committee, the Ad Hoc Cross-Cultural Communication Committee, the Urban Alliance on Race Relations). However, as an insider relates, some input counted for more: it was particularly the input of “the Black and South Asian committees” that was at the forefront of consultations.

Understanding the actors and the composition of the SCRR is important because it tells one something about how the math was done — and that math was important because “the Board soon approved the final report in toto - all 119 recommendations - and it now became the Board’s race relations policy.”

Reaction and Fall Out from the Draft and Final Report on Race Relations Issued by SCRR: In the present author’s assessment, the dominant idea systems which SCRR brings to bear on the alleged problem of racism in Toronto schools are New Left and black nationalist. It is not surprising that the political bias intrinsic in movements which are revolutionary or race identitarian will produce an analysis which is substantially unpalatable to non-radical or apolitical professionals. When the draft-report was sent around to staff and principals, the general tenor of the document and the recommendations were met with outright opposition: teachers in the consultation insisted that they were not racist and that “they treat everyone the same” and school administrators asserted that the schools did not have a significant issue with race. Marlene Green, who participated in writing the report, later recalled that “even her own superintendent thought that the document was ‘off base and extreme’” and that a number of black educators came forward in response to the draft report and represented that there isn’t a significant race issue in Toronto schools (Green claimed they were “in denial”).

As Marxist School Community Relations Department member Tim McCaskell related, in 1980, after the report was finalized and it came time to hold workshops in the board’s 132 schools on the new polices, board functionaries had a difficult time selling SCRR’s findings: they “couldn't get beyond the first part of the report before teachers ‘started saying it was all lies.’ Most of the few teachers of colour didn't feel strong enough to contradict their colleagues. And then there were always those people of colour who did get up and say, to much applause, 'I've never experienced racism, it doesn't exist.' So then what were we supposed to do?"

Pat Case, an actual member of the Communist party of Canada, and one of the first black TDSB trustees, reacted to the teacher pushback on the draft report by deciding to re-evaluate “the role of teachers and their unions in the workings of the system” — once upon a time for Communist Case, surely the workers, i.e., the teachers, were always right. Not so when they denied being racists in the face of the New Left policy manufacturing machine.

Claims of Racism from the SCRR Report — Supposed Evidentiary Basis: Due to an excess of negative feedback from teachers and administrators about the claims and argumentation of the draft report, the TDSB directed the SCRR to rewrite its introduction and “soften” its claims; as a result, claims that alleged racism in Toronto schools had to do with institutional structures, or could be demonstrated by pointing to racial incidents in the city, were removed.

There is still plenty in the introduction of the final report that the sceptical reader could object to. Even a committee that is committed to imposing 119 new school policies on the pretense that racism needs to be combatted has a hard time representing why this is a particular problem Toronto: on p. i they state, “we learned that racism is not ‘rampant’ in Toronto” nor is it more prevalent in TDSB than any other board in Canada. But it does exist, they say: for example, there have been racial incidents involving violence. How frequent? “We have no intention of creating the impression that violent incidents are common or widespread in our school system” but the potential exists “for such incidents to become more common.”

Despite that teachers overwhelmingly criticized the SCRR draft report for being “too narrow” and “sanctioning bias based on ethnicity” (meaning, they saw it as a document that one-sidedly skews policy toward the feelings and interests of minorities) the final report is decidedly “narrow” in the same way. The committee next states, in effect, that racist banter in schools could only victimize non-white students and it represents that schools must help these minorities “reject the role of victim”; it goes on to state that minorities “have a right to expect that the achievements of their races will be recognized” — what “right to expect” would that be exactly?

So, what evidence of racism does the SCRR present in its final report to the TDSB in 1979 (what is the evidentiary basis for the X recommendations it is about to make)? With a student population of 90,000 under the TDSB, the committee makes no attempt at statistical analysis. Instead, on pages 27–30, five anecdotal stories are given in order to document racial incidents at school. No names, dates or documentation is provided for any of these stories just “the teacher” did X, or “the student” did X at “a school.” The first story retells an incident where a teacher came back to the classroom only to hear “a black student shout an ethnic insult across the room at a white student”; whereupon, the teacher immediately sent the black student out of the room (p. 27). One might suppose that this would prompt the committee to re-access their framing of racism in Canadian schools as something that is a concern for minorities exclusively, but that would be missing the moral of the story as perceived by the committee: for the committee, the moral of the story is that the teacher should have asked more questions — it was probably the case that the white student had thrown racist insults first, they suggest.

Recommendations in the Final Report from the SCRR — the material reproduced below is put forward selectively by the current author and, again, appears in paraphrased plain English:

• Curriculum Overhaul and Purification: The committee recommends that teams of classroom teachers and “representatives of ethnic and visible minority groups” undertake a review of current curricula to identity materials that may be deemed racially or ethnically biased; flagged material is to be removed immediately and committees with community [ethnic] liaisons to oversee integration of new material (recommendation #1-#6). New material should a) emphasize achievements of visible minorities and their values as positive examples, and b) foreground facets of Canadian history that reveal poor treatment of visible minorities (#11); The study of race relations be built into the social studies of elementary schools and a unit on race relations and human rights be included in appropriate high school courses (#15).

• Racist Remarks are Now Officially Against Board Policy: The cognitive dissonance of the committee is sometimes rather amusing. The final report (p. 47) quotes a comment in the Toronto Star from 1973 in which the writer observes that “one the great moral prohibitions of our time is directed against frank talk about race,” that is “in the 1970’s... race is a forbidden subject.” The committee quotes this, evidently, to reinforce the importance of sensitivity about race. Despite presenting the Toronto Star’s clear assessment that Canadian society of the early 70s—well before the SCRR—was rather sensitive on racial matters, the board nonetheless put forward an elaborate set of recommendations (#31-#39) to establish that racist comments aren’t acceptable in Canadian schools and there will be consequences.

• Racial Quotas in Hiring - so close, but not yet the right time in 79: Surely, all “reformers” and race identitarians of the 70s used to dream of a time when it would be legal to discriminate against white people, especially white men, in hiring practice. They wouldn’t have to wait long: the Employment Equity Act of 1987 would normalize targeted hiring of “equity seeking” groups in federally regulated industries, and, even earlier in 1982, “affirmative action” hiring was built into section 15(2) of our philosophically weak charter of rights and freedoms.

At the time the draft report of the SCRR was being circulated in 1978, Canadian teachers hadn’t come around to the idea that Canadians should be favored for employment on the basis of the non-membership in the group white Canadian, and they firmly rebuffed anything in the draft report that struck them as courting the onset of a “quota system” — consequently, the TDSB had the SCRR remove any recommendations that had to do with term appointments “that sought to make more space for visible minority staff,” as well as a recommendation that the Board seek approval from the Ontario Human Rights Commission for “adopting recruitment and hiring measures that would address the underemployment of visible minority teachers.” I suspect that recommendation #71, calling for incentives for staff to retire early, may not have been entirely novel — it may be a moderated form of a radical policy aimed a limiting the terms of principals to 5 years which had been scrapped following blowback to the draft report (both policies likely having the intention of freeing up room for the promotion of minorities).

• Race Conscious Hiring Policies - Institutional Cancel Culture in 79: The committee recommends that principals be given new guidelines on how to hire candidates as teachers — candidates must have i) a “reasonable” knowledge of visible and ethnic minority groups; ii) positive and bias-free attitudes toward these groups. Principals to be trained in racial bias detection training (#77-#78). The same set of “positive attitude” requirements be in place for the hiring of non-teaching staff as well (#85-#86). A procedure be established for detecting racial bias in candidates for promotion on academic teaching and non-teaching staff, and guideline for promotion of the same depend on racial sensitivity and knowledge (#87-#88).

4.0 Aftermath and Legacy: The radicals consider the mainstreaming of identity politics in Canadian schools as “a testament to the victories that new leftists scored in Toronto schools in the 1970s.” One-time “reform” trustee Myra Novogrodsky recalls that it was no coincidence that radical change came in a 20 year period in which the Board was mainly controlled by trustees who voted NDP (I would add, and whose activism was New Left); it was during this period, she says, that trustees “created a School Community Relations Department, opened 20 alternative schools, hired designated staff to oversee curricular changes on gender issues, race relations and multiculturalism and aboriginal issues, and began the Triangle Program, the first Canadian school for lesbian and gay youth.” Novogrodsky’s observation that “it was mainly politicized parents that first advocated for a multicultural agenda and later for a more anti-racist perspective” is perhaps partially correct: yes, parents had been “politicized” by the New Left, but advocating for an “agenda” is the function of the New Left community organizer/agitator first, and the function of the community second.

John Barber, writing in the Globe and Mail, stated that the NDP first introduced “open party politics” to the Board in 1980, forming cliques with other NDPers, holding caucus meetings with each other before each board meeting and dominating Board policy of the time. One might add that, long before this, NDP voting New Leftists masquerading as “reformers” had long set about politicizing the board, transforming it according to a clandestine vision of reform and revolution.

The era of the New Left transformation (with its community outreach doctrine that allowed the voices of ethnic minority activists who also felt that “liberalism is not enough” to be heard) came, and, in some senses, never left. However, more recently, George Martell, as essential to launching the “reform” movement at TDSB as anyone, bemoaned the fact that provincial legislation has turned “what we used to call ‘School-Community Councils’” into “toothless shells,” school-councils run by local principals. Parenthetically, the bones of the New Left movement, its intellectual remains in the form of books, articles, documents, periodicals, are maintained by the radical connexions organization in a moth-balled room on the University of Toronto campus.

The Evolution to Anti-Racist Policy: The transformation of TDSB race policy to anti-racism would begin in the early 80s when TDSB race relations advisors Tony Souza and Alok Mukherjee began collaborating with anti-racism educator Barb Thomas to create equity training programs and “recommendations for systemic strategies to deal with racism in school boards.” It would be the anti-racism policy movement with its built-in emphasis on equity in all things (discrimination in favor of minority interests) that would emerge as official TDSB board policy in 1999 with the passing of the “Commitment to Equity Policy Implementation: Anti-Racism and Ethnocultural Equity...” policy programs. And we are certainly justified in tying this together with the policy developments examined earlier in this essay, as insiders do: “The Toronto District School Board's adoption of a broad equity policy was the climax of almost thirty years of struggle that had begun in the Toronto Board in the 1970s” (the word “struggle” here is not incidental as the sentence was written by a Marxist). The reader may be interested to note that anti-racism theory is now widespread in Canadian institutional and governmental policy and has been described—approvingly!—by Ontario education theorists as a mixture of Marxist and postmodernist theory.

Very occasionally, dissenting educators ineffectually object to anti-racist doctrine — multicultural educationalists Mansfield and Kehoe criticize it for being, among other things, far too political (quite rich coming from them!). In the memoires of the radical actors, only one man effectually stood in the way of this avalanche of “progress”: Mike Harris. They ruefully recount that the election of the Harris government in 1995 “proved to be a catastrophe in the evolution of equity,” and another concludes that it is “evident the Harris government had delayed the development and implementation of antiracist education in Toronto and stopped it completely in most other boards across the province.” Not so for TDSB, as we have seen, which passed its equity marching orders in 1999.

Bibliography

Aladejebi, Funké O. 2016. Girl You Better Apply to Teachers’ College”: The History of Black Women Educators in Ontario, 1940s – 1980s. Ph.D., York University.

Albo, Gregory. 1990. “Canada, Left-Nationalism and Young Voices.” Studies in Political Economy: A Socialist Review: 161–174.

Alinsky, Saul. 1971. Rules for Radicals: A Practical Primer for Realistic Radicals. New York, Vintage Books.

Bracke, Maude Anne. 2014. “1968.” In The Oxford Handbook of the History of Communism, edited by Steven A. Smith, Oxford: Oxford University Press: 156–171.

Breines, Wini. 1980. “Community and Organization: The New Left and Michel’s ‘Iron Law.’” Social Problems 27/4: 419–429.

Breton, Raymond. 1986. “Multiculturalism and Canadian Nation-building.” In The Politics of Gender, Ethnicity in Canada, edited by Alan Cairns and Cynthia Williams, 27–63. Toronto, Buffalo, London: University of Toronto Press.

Canen, Ann and Michael Peters. 2005. “Issues and Dilemmas of Multicultural Education: theories, policies and practices.” Policy Futures in Education, Volume 3/4:309–313.

Carr, Paul. 1996. Anti-Racist Education, Institutional Cultural and the Search for Educational Transformation: A Case Study of the Toronto School Board of Education’s Secondary Panel. Ph.D. diss., University of Toronto.

Churchill, David. 2001. When Home Became Away: American Expatriates and New Social Movements in Toronto, 1965–1977 (vol. 1). Ph.D. diss., The University of Chicago.

Connelly, Michael F. and Jean D. Clandinin, 1984. The Role of Teachers’ Personal Practical Knowledge in Effecting Board Policy, vol. II: Development and Implementation of a Race Relations Policy by Toronto Board of Education. Ontario Inst. For Studies in Education, Toronto.

D’Souza, Dinesh. 1991. Illiberal Education: The Politics of Race and Sex on Campus. Free Press.

Edmonds, Victor. 1971. Definition of the Free Schools Movement in America, 1967—1971. Ph.D. diss., Ohio State University.

Fine-Meyer, Rose. 2012. Including Women: The Establishment and Integration of Canadian Women’s History into Toronto Ontario Classrooms 1968-1993. Ph.D. diss., University of Toronto.

Gaskell, Jane and Ben Levin. 2012. Making a Difference in Urban Schools Ideas, Politics, and Pedagogy. Toronto, Buffalo, London: University of Toronto Press.