Woke Watch Canada is a reader-supported publication. Please consider becoming a paying subscriber or making a one-time or recurring donation to show your support.

(As part of Woke Watch Canada’s on going series about great Western books, like the 11-part essay series by anthropologist Geoffrey Clarfield, My Non-Woke Personal Library and Its Saving Virtues, today we continue the theme with a previously unpublished essay by Barbara Kay).

There is a telling little section in Barbara Kay’s book, Acknowledgments: A Cultural Memoir and Other Essays, where she discusses her adolescence. It was one particular summer, when faced with the choice to either get a job and spend the summer earning money, or forget the job and spend the time reading classic Russian literature, Barbara went with the Russians; Clearly, the right choice.

I think often about this essay (the first in her book) in which she described her past life with her supportive family. That she chose immersion in the world of Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky means, at least to me, that Barbara is complex and cool, and she has been that way since she was a kid. I am embarrassed by the types of choices I made, and how I spent my time, when I was a teenager and in my early twenties. Barbara Kay, apparently, has always been Barbara Kay - and that is extraordinary!

In her words:

“…one summer I just stayed home - with my parents’ approval and indeed pride - to read all the great Russian novels, one after another, with no distractions.”

When I read of this season spent with the Russian literary greats, I decided then and there that I would add something similar to my bucket list. If I ever retire, the first thing I plan to do is read the greatest works of the main Russian authors - Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, Chekhov, Pushkin, Gogol, Solzhenitsyn, Turgenev, Nabokov, and others - “one after another, with no distractions.”

I have read Crime and Punishment, which I firmly believed changed me as a person, although I can’t quite say how. It made me more aware of certain things, like the torture of poverty and the boredom and hopelessness that surrounds it. When a young man is not able to express his energies and vigor in productive fruitful work, when he cannot set himself on a path towards prosperity and support a family, a volatile situation arises with violence always one outburst of frustration away from rearing its ugly head.

I hear The Brothers Karamazov is fantastic. But I have not yet read it. When at last I get to my Barbara Kay-style uninterrupted Russian reading extravaganza, I think I’ll start with the Brothers.

My point is not to digress on an extended exposition of Russian literature, but only to express that from when I first started reading the columns and essays of Barbara Kay, I have been strangely able relate to what she writes, even though much of it is well outside my sphere of experience, but also, I have had my understanding elevated and my perspective sharpened. For a long time, Barbara Kay has been required reading. Like Dostoyevsky, albeit much less violently and disturbingly, Barbara has changed me; is that not what great writers do for their readers?

Another thing on my bucket list is to some day write a book about my favorite Canadian writers and thinkers. Chapters would include such figures as Harold Innis and Marshall McLuhan, Northrop Frye, Tom Flanagan, George Grant, Pierre Berton, J. L. Granatstein, Jordan Peterson, Eric Kaufmann, Nina Green, Frances Widdowson, Conrad Black, Rex Murphy, and of course, Barbara Kay.

But all of this is in some distant translucent future. A beautiful vision of Russian literature and writing about Canadian intellectual icons. The coffee will flow like rivers through my office. And the greatness, in letters, will surround me, and probably change me, like it always does when it’s really good. I do hope and intend to live this vision. We will see.

As for the present. It is my great honour to present to readers of Woke Watch Canada an unpublished essay by a great Canadian thinker and writer: Barbara Kay. And, to really connect all the dots of my far too long preamble, Barbara’s essay is a literary themed one. Not Russian literature though (the bit above about the Russians was just a fun little side adventure).

Today’s essay is about Thomas Mann’s Joseph and his Brothers. A fictionalized account, which draws from the historical record of the Old Testament. Joseph’s brothers sold him into slavery out of the jealousy that resulted from the favoritism shown to Joseph, by their father Jacob (whose name, in adulthood, after demonstrating his willingness to let God prevail in his life, was changed by God to Israel. And he was promised all the blessings that were pronounced to Abraham).

Great books and great writers always deal with heavy themes, although not always without humour. Barbara, and Thomas Mann, are no different.

Enjoy!

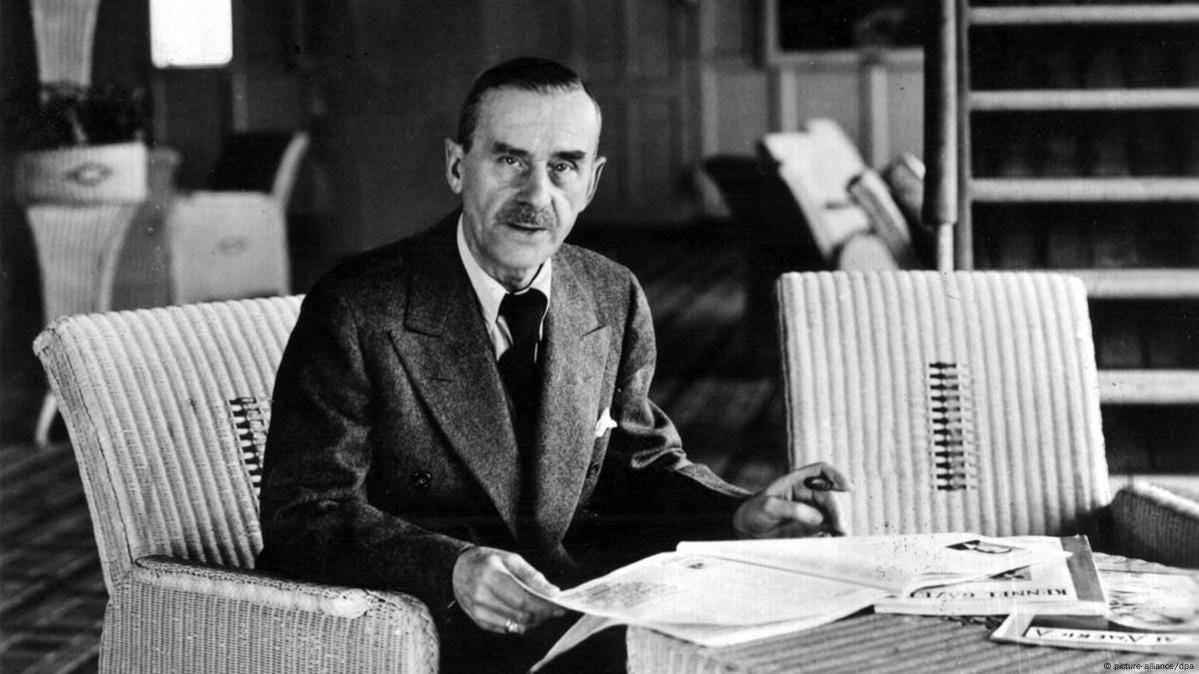

Thomas Mann: Joseph And His Brothers

By Barbara Kay (opinion columnist at the National Post since 2003)

Preamble

My birthday falls in late November, and has always coincided with some point in the lead-up to, or the actual Joseph story in the weekly synagogue Torah readings. So Joseph, of all my ancient forebears, always had a special significance for me.

When I was young, I found the action of Joseph’s brothers – throwing him down the dry well, then selling him to passing traders – horribly cruel and disturbing. As I grew older, the story led me to understand the powerful effect of parental favoritism on siblings, and the extent of the resentment it can foster.

The reunion of Joseph and his brothers in the Torah is one of the great scenes in the Bible. But so much of what passes between them is cryptically rendered. I always wished for more detail.

My 40th birthday was approaching. I wanted to celebrate with a Jewish component. I had never had a bat mitzvah. I thought I might do a presentation in synagogue on the Joseph story to mark the occasion.

I discussed this possibility with a literarily inclined friend, who urged me to read and deliver my “d’var Torah” – a commentary on the weekly portion - on Thomas Mann’s Joseph and His Brothers.

I’d read a number of Mann’s books: The Magic Mountain, his most famous novel, Buddenbrooks, and The Confessions of Felix Krull, Confidence Man. And I’d of course also studied Mann’s famous novella, Death in Venice, in school.

I say “of course,” but that was a long time ago, when Mann’s was a household name and greatly revered. I daresay Mann is no longer part of most school curricula, being white, European, dead and a reminder of oppressor culture.

I admired Mann, but he’s never an easy read.

I had no idea what I was in for. Reading the four-volume novel (mine was a single small-font edition of 1100 onion-paper thin pages) was one of the great literary experiences of my life. It’s a stunning achievement in art. And it inspired me to share my enthusiasm for it with others.

I did end up giving a d’var Torah on Mann’s Joseph in synagogue to celebrate my 40th birthday. But I held one thought back. Mann’s Joseph is gay. Of course, he never actually says that in the text, just as he never says Gustav von Aschenbach, the aging writer obsessed with the beautiful young boy Tadzio in Death in Venice, is gay. But the reader knows. A writer of genius has his strategies.

So perhaps that is why Thomas Mann, a bourgeois man, but a complex artist with a strong penchant for homoeroticism, was so drawn to Joseph as a protagonist.

That was not, though, something I felt would be an appropriate discussion point in synagogue – even a liberal one as mine was then - 37 years ago.

Sometimes I feel as though I want to reread that magnificent tome. At my age, it is a daunting proposition. I’m too busy. But if I were in forced quarantine with nothing else to do, I just might.

Thomas Mann’s Joseph and His Brothers (JAHB) is a panoramic narrative of the Books of Genesis from Abraham forwards, faithfully based on events as they are presented in the original. If we think of the Bible account – and I often do – as a poetically composed series of stylised sepia prints, Mann turns them into a lavish film with a cast of thousands. He fills in the gaps for the modern reader as the oral tradition must have done for the ancient listener. When I finished reading it for the first time, I said to myself, quite irrationally I suppose, exactly what Mann’s secretary said as she placed the final pages of the first novel in manuscript on his desk: “Now at last we know what really must have happened.”

Perhaps I was particularly taken with the book because of my meagre historical imagination. De Tocqueville has pointed out this weakness as a feature of democracy – that it cuts us off from our historic roots. Not surprisingly then, the literary form most closely associated with the rise of the democratic philosophies is the history-packed novel. In the Bible I find the repetitions, the elliptical jumps, the broken story lines, and the sing song rhythms of the prose (ideal for memorizing? audience), unsuited to my own penchant for narrative continuity, character development and exploration, and a structured plot.

Descriptive, continuous prose is what speaks to my modern imagination. I find the omissions in the original version quite maddening. For instance, in the Dinah story, what did Jacob say when Shimon and Levi roared to him in justification of their deceitful violence upon the Shechemites, “Shall our sister then be treated like a harlot?” What a strange ending for a story from our point of view.

Well, Mann tells us what Jacob said, or at least what he might have said, given his character, his principles and the tribal customs of the day: “Yes,” he screamed to their horror, “rather than endanger our lives and the blessing.” Goethe once said, of the Bible tales, “This natural story is highly amiable, only it seems too short, and one is tempted to carry it out in all its details.” This was the remark that first inspired Mann to write this novel, and so to recreate in a modern idiom, the mythology common to all of Western civilization.

Perhaps this word ‘mythology’ is the most sensible way to begin speaking about JAHB, as it is sometimes liable to misinterpretation. The word ‘myth’ comes from the Greek ‘mythos,’ which means ‘plot.’ In everyday speech we often mean by a myth a story that is not factually true and is therefore irrelevant or misleading. Its significance for culture and literature in particular is almost the opposite. I like Northrop Frye’s definition of a myth because it is short and to the point. Myths, he says, “are the stories that tell a society what it is important for them to know.”1 Folktales, by contrast, are stories of entertainment and are interchangeable amongst cultures. One is sacred (myths) and forms the basis of work such as Milton’s and Dante’s; one is profane (folktales) and appears, for instance, in Chaucer and Shakespeare.

Mythology is a civilization’s canon of “concerned knowledge” and is the most important factor in transmitting a heritage of shared allusion, and thereby creating a cultural history. “The myth conveys the universal in the event. It is designed not to describe a specific situation but to contain it in a way that does not restrict its significance to that one situation.”2 Mythology is “heilsgschichte,” the history of God’s actions in the world and man’s relation to them. World events are simply “weltgeschichte,” our human idea of history.

Thus, from the mythological point of view it is not very important that Egyptologists find no record of the Exodus in Egyptian history. The Exodus, the deliverance from oppression and the acceptance of the Law, happens to be our critical myth. Everything else that transpires in Genesis from Abraham on is prelude and forerunner to it. And therefore too, the modern rewriting of the myth is no more or less authentic than the original narrative, as long as it continues to tell us what we should know.

It is important, if a mythology is to have impact on a people, that it be unified. A unified mythology can be a powerful instrument of social authority. What Mann stresses as the significant unifying element of the Genesis is the motif of recurrence. There is nothing original in this emphasis, of course. Often we have read and discussed the repetition of certain events and situations in these stories: the denial of the birthright to the firstborn, the gentle brother-wild brother theme, the scourge of barrenness that afflicted all the patriarch’s wives. But Mann goes well beyond these conventional inferences from the text.

Drawing on his encyclopedic knowledge of human history, Mann extends the horizons of the recurrence motif backwards and forwards in time. For example, in Egypt his Joseph assumes the name Osarsiph, which means ‘In death I have forgotten my father’s house,’ because of course Joseph considered that he had undergone a form of death, knowing that his father must believe him killed. Any name with the prefix Osar or Osir or Usir in Egyptian contains the concept of death, because Osiris is the death god in their mythology. Osiris was the ‘mangled god,’ who was carved up by his brother and sent down the Nile where he was miraculously restored to life.

When Joseph tells an Egyptian his name is Osarsiph, the Egyptian asks, “Are you born from the reeds? Are you an Usir in the rushes? Did the mother search and find you in the water?”3 Now Joseph is linked backwards to Egyptian mythology and forwards to the Moses story. I should add, by the way, that Mann’s references to Egyptian history and mythological sources may be taken as gospel. He could certainly have rested on his laurels as an Egyptologist alone, and his knowledge of every facet of Egyptian culture is simply astonishing.

On the other hand, there are certain linkings that are purest invention on his part and are added to strengthen his case that ‘Once upon a time,’ as he puts it, means both past and future time. Such an artistic addition is Mann’s having Judah sell Joseph to the Ishmaelites for 30 pieces of silver (they finally settle on twenty after haggling), and hypocritically kissing him on the cheek as they take him away, thereby linking Judah to the future Christ story and Judas who betrayed him.

In addition to extending the boundaries of thematic recurrence in time, Mann makes the spatial landscape extremely dense in comparison with the rather sparsely scattered linking patterns already present in the original. Interestingly, although Mann did not read the Bible in Hebrew, he had already anticipated Robert Alter’s brilliant explorations of the narrative text in The Art of Biblical Narrative, and built on them to weave a luxuriantly textured fictional fabric. For example, Alter shows us that the use of key verb roots links events from different parts of the story. Mann goes much further in his treatment of linking devices.

Take, for instance, the celebrated “coat of many colours,” which appears for the first time in the Bible when Jacob presents it to Joseph as a boy of 17. In Mann, the coat makes its first appearance as Rachel’s wedding veil, a magnificently embroidered and concealing garment in which early tales and legends are sewn into the design. Thus, when it first appears in the Joseph story, the veil is already linked to the distant past. From its first use as Leah’s deceptive protection, it is associated with human passion, extremes of love and hate, and tinged with an erotic cast. Mann’s Jacob keeps the veil with him always, and it becomes especially precious to him after Rachel’s death.

When Joseph, a narcissistic seventeen, glimpses the veil, he is overcome with desire for it. He is consumed with self–love at this point in the story: Jacob doesn’t give it willingly; Joseph wheedles the veil out of him, plying his considerable charms and rhetorical ability to wear Jacob down. Later, in wearing the provocative garment on his visit to his brothers, Joseph deceives Jacob, who would certainly not have allowed him to, knowing that the brothers would quite logically see in it Joseph’s claim on the birthright.

Mann’s projection of the scene in which the brothers rip the veil from Joseph, bind him and cast him into the dry well carries overtones of rape, setting Joseph’s delicacy and innocence against the rough masculinity of the brothers. This image is compounded when the coat/veil is returned to Jacob smeared with blood.

The garment and blood imagery is carried forward in the seduction scene with Potiphar’s wife (Mut-em-enet), when, having ripped Joseph’s garment off him, she bloodies it with self inflicted wounds of frustration, and then shows the incriminating material to Potiphar. Again, Joseph has been falsely accused (in the one case of seduction, in the other of presumed death), once by a father, once by a father figure (as Potiphar is in JAHB); and again he goes down to the pit. Other examples of the same technique abound in JAHB.

Lest you think, however, that the novel is so freighted with images and symbols and myths that it is in danger of sinking under its own weight, I must point out that the prevailing tone of the books is playful and entertaining. Mann himself once referred to this work as “a humourous poem of mankind.” It is not the punitive and corrective humour of satire, nor the aggressive intellectual humour of wit, but the gentle humour of mankind seen through the eyes of the gods, man caught in the act of being himself.

If there is one consistent feature in the book that throws events into this humorous light it is in the public nature of the story as Mann tells it. From the Biblical account you have no sense of any human involvement in the story other than the principal characters of each event, so the emotions are intense and serious. By telescoping the reader’s point of view so that he watches the action, along with the hosts of people who would normally be there in the ordinary course of events for that day in any case, the action takes on a completely different affect.

Let me give you one small example.

In Genesis, Chapter XXVII, verse 30, we have the famous story of Esau realizing that his birthright has been stolen, and Isaac’s attempt to set things right, with both principals in anguish over the catastrophe of Jacob’s duplicity. Their dialogue takes place (apparently) while Esau and Isaac are alone in Isaac’s tent. The whole affair – Esau’s return with his kill, the cooking of it, the dialogue – seems to occur in a brief window of time. But in Mann’s version, one gets the “real” story.

This incident plays out over the course of a whole day. The build-up to the climax is tense, with the protagonist unaware of what will happen, but everyone else in on the “joke.” There are men, women and children all over the place, and everyone knows exactly what has happened, because - it makes sense – in those days, nobody was ever really alone with anyone. Privacy had not yet been invented.

So first Mann tells the reader that following Jacob’s exit, “matters became both comic and tragic.” Esau arrives from the hunt in high spirits, “[p]uffed up in pride and self-esteem.” He looks around him at his fellow tribesmen and their servants, expecting deference and awe at his prowess. He doesn’t notice that everyone is giggling and hiding their merry anticipation of what is to happen to him.

Esau strips the animal he has killed and goes about the long process of cooking it, boasting of his prowess as he does so to the big-eyed circle around him. “Ho, ho! Ye godly gapers! Fetch me the great cook’s fork. And bring me sour milk of the sheep for he savours it best seethed in sheep’s milk” (this is a typically sly Mannism, triggering the alert reader to remind him that the laws of kashrut, prohibiting the mixing of milk and meat, had not yet been invented). These commands go on for a paragraph. “For it is the feast of the feeding and the blessing of Isaac, Esau’s feast, the feast of the hero and son, whom the Lord hath sent to make him a meal, and whom he will bless within his tent in this hour.”

Then he went on, with mouth and hand, with ha, ha! And ho, ho! And bombast and braggadocio, with windy boasting of his father’s preference and the great day come to the red skin; so that the folk of the household bent double and writhed with laughter and wept and held their sides. He went off with his dish, holding it high before him like the tabernacle, and throwing out his legs and prancing up to his father’s tent; and they shrieked aloud, clapping and stamping their feet – and then were suddenly still. For Esau, at the door of the door, was saying, “Here am I, my father.”

JAHB is about humanity. Humanity and the links that bind man to each other are Mann’s, the humanist’s, obsession as much as God and the covenant were Abraham’s, Isaac’s and Jacob’s. Mann said that in Genesis he found himself entertained by “the novelty of dealing with human beings who did not quite know who they were or who knew it in a more pious, deeply exact way than the modern individual.”4 He continues:

I dwelled on the birth of the ego out of the mythical collective, the Abrahamic

ego which is pretentious enough to assume that man should serve only the Highest,

from which assumption the discovery of God followed. The claim of the human’s ego’s central importance is the premise for the discovery of God…5

Mann’s thesis takes form through the lives of the forefathers of Western civilization, both in its Hebraic mode (the three patriarchs) and in Joseph, the link to Hellenism that is prefigured in the Egypt of his day.

Abraham and Isaac are dealt with at what would be considerable length in a conventional novel, but at a modest length for this behemoth. Abraham’s greatness is summed up in his having turned away from what Northrop Frye refers to as the ‘metaphoric’ or animistic phase of history. In the metaphoric age, the age of Homer and the earliest Biblical records, the gods (plural) were taken to be the force of nature they represented. To the ancients, Astarte was not the goddess of the moon, she was the moon. Human beings saw themselves too as undifferentiated in nature from the gods and the animals, all revolving together through an endless cyclical eternity. In such a scheme, little spiritual progress can be made.

Abraham’s discovery of God thrust him into what Frye identifies as the metonymic age, where one thing is put for another. The great symbol of this spiritual advance is, of course, the non-sacrifice of Isaac, where the ram is substituted for the child, denoting then and for all time the importance of the concept of sacrifice as opposed to the object sacrificed. This leap into the realm of abstract religious thought is a great step forward in “heilsgeschichte.”

Now Abraham’s God is not a god in nature but a Being beyond nature. Released from the metaphor, God no longer has need of a personal history – no earth-mother or any of the other tiresomely similar genealogies, a characteristic feature of less advanced cultures. Instead of a past, Abraham’s God has a future, and Abraham is represented as his partner, his friend in a common venture. So closely identified with each other are they at this stage that Abraham hardly feels himself a separate being. Thus his conversations and plea bargaining with the Almighty seem almost like conversations with an alter ego.

But it is in Jacob and Joseph and the disparity in their characters that the greatest fascination of the novel qua novel lies. Mann presents Jacob as a single-minded knight in his passion to fulfil the covenant. Unlike Abraham he is quite separate from God; indeed he is in great awe and fear of Him. Only one other thing in his life absorbs his energy and concern, and that is his towering love for Rachel, a love which is transferred after her death to Joseph and Benjamin, her only sons.

Jacob was no scholar – insofar as one could be a shepherd and scholar in those days – and mistrusted learning, which is of course not the traditional Jewish view of him. In fact, Mann’s Jacob was deeply suspicious of what in general we might call ‘culture,’ identifying it with the land of Egypt, which to Jacob stood for all things corrupt. For Jacob, Egypt was “the home of immorality and feudal abuse.” He refers to Egypt as Sheol, “the land of mud,” “the land of monkeys,” where death and the past are worshipped and the people are insensible to sin.

Jacob is severe, obsessive, insensitive on the personal level, a consummate, often self-pitying sufferer. After Rachel’s death he surrounds Joseph and Benjamin with a morbid, melancholy blanket of tortured love. His love for the beautiful Joseph, whom Mann describes in frankly androgynous terms, is excessive, idolatrous. When Joseph puts on the coat of many colours for the first time, Jacob is shocked by his resemblance to Rachel. Later he is punished for his too intense (but not erotic) attachment to his son. Playfully Mann suggests that this God, the first to be wifeless and childless, is an unusually jealous God as well. In any case the idolization of another human being is a sin.

Sin and the avoidance of sin obsesses Jacob. Before Abraham there was no concept of sin in the world. With man’s discovery of God came an awareness of a mode of life unacceptable to him. Mann gives us an interesting definition of piety and sin. Piety, he says is:

attentiveness to the inner changes of the world, the mutation in the aspects

of truth and right; obedience which loses no time in adjusting life and reality

to these changes…To live in sin is to live against the Spirit (Zeitgeist), to cling to the antiquated, the obsolete, and to continue to live in it because

of inattentiveness and disobedience.6

By this definition Laban is a sinner because he continues to believe child sacrifice to be efficacious in bringing good luck to a home. He stuffs his infant son into a jar and buries him alive under the foundation of his house. Here is one with no ear for the inner changes of the world.

On the other hand Mann commends Judah for not killing Joseph outright at the well, crediting him with the insight that such a custom was no longer appropriate to the times they now lived in. In effect Mann says we cannot judge ancient passions and actions in the light of our highly evolved system of personal morality. For God only expects from man what he is capable of in his day. In that connection here is a thought that Mordecai Kaplan, founder of Reconstructionist Judaism, would commend:

For God too is subject to development; He too changes and advances,

from the desert-like and demonical to the spiritual and Holy; and He can

do so without the help of the human spirit as little as the human spirit

can do without Him.7

Jacob is austere, weighed down with the covenant and its terrible responsibilities. Joseph, on the other hand, is far more complex: a boy of great charm and charisma, and a young man avid for learning. There is also of course the vanity which precipitates the whole action of the story. But vanity is too simplistic a word to convey Mann’s understanding of Joseph. He says of him:

There is one who has not only discovered God, but knows how to ‘treat’

Him; one who is not only the hero of his stories, but also their director,

indeed the one who poetically “adorns” them; one who it is true still

participates in the collective and mythical, but in a banteringly spiritualised

and playful, purposefully conscious manner. In short, we see how the ego in

the process of its emancipation soon becomes an artistic ego, attractive,

delicate and – endangered.8

This artistic ego – and it quickly becomes clear that Joseph is in many ways a ‘persona’ for Mann – is amazingly egocentric in its youth; it believes everyone holds him as dear as he holds himself. But along with this narcissism in Joseph’s case there is what Mann calls a “friendliness to humanity.” As Joseph matures, the social and communal side of his character assert themselves, so that in the end he is his family’s benefactor in more than the material sense; he has become truly outer-directed. Mann’s lifelong struggle to integrate his own artistic egoism and his attachment to the bourgeois order is mirrored in Joseph’s development, and at the end of the novel the conflict is movingly resolved.

In Joseph’s youthful dream of the sheaves and the stars, it is clear enough what meaning the dream’s action held for him. But so transformed has he become in his maturity at the end of the book that in the great reconciliation scene with his brothers, he can say in real humility:

For your brother is no god-hero, no harbinger of spiritual salvation. He is

just a farmer and manager (this refers to his role as Pharoah’s vizier).

Remember how your sheaves bowed down to mine in the dream…and the

stars that made curtsies? Well, that has turned out to mean nothing so very extraordinary: just that my father and brothers would thank me for what I could give them. When a man receives bread he says not ‘Hosannah is the highest,’ but just ‘Thank you very much.’ However, bread there has to be first before all the hosannahs.9

Another important theme is Joseph’s role as the first Disapora Jew. Of course both these words, Diaspora and even Jew, are anachronistic, for this tiny tribe of Hebrews had not yet taken possession of their sacred land. Nevertheless, Jacob certainly thought of himself as the collective ‘Israel,’ the name he had earned wrestling with the angel. And as a family Jacob’s little tribe were conscious of their separateness from their neighbours. Joseph went down to Egypt steeped in that sense, and he remained conscious of himself as set apart all his life, although he was barely out of boyhood when he left Canaan.

And what was the Egypt of that day to a shepherd boy from the sticks of Canaan? It was Paris, London and the lights of Broadway. Mann describes the Egyptians as a cosmopolitan and trendy people, playful and fun-loving, disdainful of foreign ‘cultures,’ at the same time curious about them, and tolerant enough to find certain foreign traits chic. Mann evokes the atmosphere of the country in this way:

For the prevailing tendency was fin de siecle, it was that of a society

composed of descendants and heirs, already remote from the patterns of the founding fathers…It appealed to Joseph, for he himself was late, too, in time and in his soul, a very good specimen of a descendant, volatile, witty, difficult and interesting. So he felt like a fish in water…10

The conflict Joseph experiences between fidelity to the covenant – as represented for him by his vision of God with Jacob’s face – and his appreciation of the culture around him is the ages-old tension between Hellenism and Hebraism. Hellenism is the celebration of the striving toward intellectual and aesthetic perfection; Hebraism the submission and commitment to moral imperatives.

Now Jacob, dwelling in the Holy Land, is the complete Hebraist. When he hears one of his little grandchildren singing a poetic song (rendered in the form of little verses of the German romantic type), he admonishes her:

For poesy, dear little one, poesy is always and alluring, seductive, dangerous

thing…Poesy is play of heart and mind; willingly I applaud it, so long as it loses not sight of spirit but remains in the end concern with God…For God is a high and difficult task, but the ‘gods’ are a pleasant sin.11

But for Joseph the world of aesthetics, so sympathetic to his basic personality in any case, is not to be dismissed so cavalierly. Mann treats Joseph’s first entry into Egypt at some length, as he makes a leisurely progress down the Nile with the band of Ishmaelite traders. Overwhelmed by his first impressions of the cities, the beauty of the temples, the artistic variety of their handiwork, Joseph is perceived by Mann thus:

This was culture which smiled down upon him from the walls and (Joseph), a

little worldly as he was…rejoiced in the sight – always with a silent reservation, a thought of the too-spiritual minded father, who would have objected to all this picture making. ‘It is charming to the last degree,’ he thought; ‘admit it, old Israel and revile not this achievement of Kempt’s children…for perhaps it might even be pleasing in the sight of God Himself. I feel friendly toward it and find it exquisite – despite the consciousness in my blood that probably the real and important thing is not to carry nature’s handiwork into the high heaven of good taste but rather the urgent need of care for God and the future.12

No European shtetl Jew, thrust suddenly into the religious freedom and the dazzle of the Enlightenment, could have experienced this tension more keenly. The parallels are painfully clear. Mann’s personal sensitivity to the Diaspora experience is also reflected here, but I shall say a word more of that anon.

Joseph’s pharaoh is a fascinating figure in the novel, a sickly, neurasthenic, but sincere and gentle fellow. Mann espoused the widely held theory that he was Amnahotep IV who took the name Ihknaton to demonstrate his allegiance to the one God, Aton. His conversations with Joseph are wonderful excursions into the realms of Egyptian culture and mythology, and show how close this pharaoh was to embracing the God of the covenant. Mann calls him “an anticipating, a premature Christian – the mythical prototype of those who are on the right way but are not the right ones for the way.”13

Remote and detached from his people, physically weak and lacking the political insights to win him the hearts of the masses, he fails to communicate the truths he has himself grasped, and is unable to pass on his enlightened views. In this respect he makes a wonderful contrast to Jacob in the short scene where he greets Jacob in audience. Pharaoh is only too conscious of his frailty and short lifeline, while Jacob, though very old, is still robust and charismatic, “the wise, experienced old man whose position in time was at the very source and fount of widely developing being.”14

In connection with this meeting between the pharaoh and Jacob, one humorous but ironic little vignette made quite an impression on me. When Jacob and the brothers come down to Egypt, there is a very touching reunion scene between Joseph and Jacob. This is alluded to cryptically in the Bible. In Mann’s version, after they have embraced, Joseph whispers to Jacob, “Father, can you forgive me?” By this he means can Jacob forgive him the arrogance that had set the entire action of the story in motion.

But in asking the question he is also concerned to know where he stands in regard to the birthright. Surely this must have been uppermost in his mind from when he first knew Jacob was still alive, although in the Bible such clandestine motivations must almost always be inferred from the text, which only describes actual events. Not so Mann, happily for the reader. Jacob whispers back to Joseph that he has foregone the birthright, and Joseph accepts this disappointment with grace.

But almost in the same breath, showing that this too is uppermost in his mind, Joseph feels impelled to caution Jacob about his (Joseph’s) delicate position in Egypt as a foreigner with unusual powers. Joseph well remembers Jacob’s single-mindedness in his own cause and his contempt for the Egyptian ways. In spite of his almost supreme authority in this land, Joseph is afraid that his father, the ‘grinneh’ (the “green newcomer”), will insult the Egyptians and undermine his position. He says to Jacob, “Do not let the people of this country see what you think of them.”15 And before his audience with the pharaoh, Joseph says to Jacob, “…remember that I have a position among the children of Egypt and you will not criticise their children before Pharoah their king because of the way their customs appear to you’ for that would be a mistake…”16

Picture the two of them: Jacob, a weather beaten shepherd, bearded with long woolly hair falling over his rough smock; and Joseph, smooth-faced, eyes made up with shadow and liner in the Egyptian style, wearing a geometrically styled, ringleted wig, encircled with a jewelled filet, perhaps a scarab in gold at the forehead, gold bracelets on his oiled, bare arms, his tanned body draped in a thin, pleated tunic of fine linen, adorned with the heavy gold chain of office given him by Pharoah himself. Imagine the contrast and you will catch the humour and irony of the situation. Joseph must have looked to Jacob like a punk rocker to a European zaideh.

Joseph has become too worldly to receive the blessing. There is no doubt, though, of his having remained faithful to God. Proof of his fidelity lies, of course, in the story of Potiphar’s wife (Mut-em-enet). This story occupies several hundred pages of one of the four novels; she is the female ‘lead’ in her novel just as Rachel and Tamar figure largely before and after her. Respect for the reader’s patience constrains my instinct to elaborate on this fascinating sequence, but I would simply mention that it is not the cut-and-dried affair we read in the Torah, that Joseph (still wanting the limelight) is not entirely blameless, and that, literally speaking, it is a fantastic inversion of the medieval courtly love convention, go-between and all.

Joseph has remained faithful to his people and his God, but his sympathies are too tolerant, too accommodating, too self-conscious for him to receive the blessing. Jacob says to him,

“You are blessed, my dear one…with blitheness and with destiny, with wit and with dreams. Still, it is a worldly blessing, not a spiritual one…(God) has elevated and rejected you both in one…beloved child, and you are wise enough to be able to bear it.”17

Jacob does, of course reserve a special blessing for Joseph’s sons Ephraim and Manasseh, who are portrayed as the ‘young bloods’ of Egyptian high society, annoyed at having to leave their gazelle hunting to visit their tiresome old zaideh to whom they must speak Canannitish, a decidedly infra dig. language in their eyes. Of course, in blessing them, Jacob reverses his hands because “…to his way of thinking, the blessing did not work unless there was a trick in it.”18

JAHB was written between the years 1925 and 1943. It was begun in Germany, broken off when Mann went into exile because of his anti-fascist views, and resumed again in Switzerland and America when his daughter bravely returned to Munich to retrieve the notes he had been forced to leave behind. I didn’t mention these facts earlier as might have been logical, because the question of events of that time was one I wanted to leave until the end. Knowing the dates of this novel, a reader might be very curious as to why Mann should have been dealing with ancient history at such a critical moment in contemporary history.

Mann gave a very full and interesting account of his reasons for dealing with the Bible in a speech he delivered in Washington in 1943 upon the book’s publication. Here are some of his comments:

Some people were inclined to regard JAHB as a Jewish novel, even as merely

a novel for Jews. Well, the selection of the Old Testament subject was certainly not mere accident; most certainly there were hidden reasons, defiantly polemic, between it and certain tendencies of our time which I always found repulsive from the bottom of my soul…To write a novel of the Jewish spirit was timely just because it seemed untimely. And, it is true, my story always follows the dates of Genesis with semi-jocular faithfulness, and often reads like an exegesis and amplification of the Tora, like a rabbinical midrash.19

He goes on:

In a discreet and unpathetic manner, the case of mankind is tried in it: and

therefore the manner in which the book treats the myth is so different from a certain contemporary manner of employing it – a malevolent and anti-human manner whose political name we all know.

After all the word “myth” has a bad reputation nowadays… In (JAHB) the myth has been taken out of fascist hands and humanised down to the last recess of its language. If posterity finds anything remarkable about it, it will be this.20

We come back to the unification of humanity then as the beginning and end of Mann’s purpose. Just as the whole great novel is a wonderful amalgam of many literary traditions, linguistics, mythologies, motives, memories and allusions borrowed from innumerable human spheres, up to and including Joseph himself, who is a Roosevelt New Dealer in his management of the Egyptian economy, so is Joseph himself a kind of transparency in his constantly shifting facets and illuminations, a synthesis of Hebraism and Hellenism, the two principal pillars of western civilisation.

It is a small wonder then that Joseph, one of the three alter egos in whom Mann felt he had touched real greatness (the others Buddenbrooks, and The Magic Mountain), should appear as a Diaspora Jew when Mann himself wrote half the book in a state of permanent exile. Of those years he said:

The diaspora of European culture which we are witnessing, the arrival of so

many of its bearers…to these shores…to complete their work in the American air of life – that is something very strange and unprecedented; it opens unexampled possibilities of exchange…and may be supremely helpful in creating the new feeling of significance of the coalescence of the hemispheres, of the unification of the earth.21

Mann believed that the European diaspora in America would help to bring about a new humanism of which JAHB is the emblem. Obviously his vision has failed to materialise. Today the unification of mankind seems a forlorn hope indeed.

But that Mann’s prescription for humanity’s ‘weltgeschichte’ has not come to pass in no way diminishes the awesome and inspiring distinction of his work any more than man’s failure to fulfil God’s ‘heilsgeschichte’ diminishes the centrality of the Bible in our lives and its attendant power to dignify our endeavours. And far from distracting us from the original, JAHB makes us cherish it anew.

Thanks for reading. For more from this author, read Lord Arthur James Balfour: The Accidental Zionist Who Changed…Everything

Follow Woke Watch Canada on X - @WokeWatchCanada

Support Woke Watch Canada by upgrading to a paid membership:

Or, by contributing to our Donor Box:

The Great Code, by Northrop Frye (Academic Press Canada, 1982), p. 33

Frye, p. 46

Thomas Mann, Joseph and His Brother, (Knopf, New York, 1981), p. 531.

T. Mann, Atlantic Monthly, p. 95.

Ibid., p. 97

T. Mann, Atlantic Monthly, p. 98.

Ibid., p. 98

T. Mann, Atlantic Monthly, p. 98.

T. Mann, JAHB, p. 1116.

T. Mann, JAHB, p. 562

T. Mann, JAHB, p. 1133.

T. Mann, JAHB, p. 573.

T. Mann, Atlantic Monthly, p. 96.

T. Mann, JAHB, p. 1162.

T. Mann, JAHB, p. 1152

T. Mann, JAHB, p. 1158.

T. Mann, JAHB, p. 1155.

T. Mann, JAHB, p. 1182.

T. Mann, Atlantic Monthly, p. 96.

T. Mann, Ibid, p. 99.

T. Mann, Atlantic Monthly, p. 100.

Excellent, thank you!

I’m about 95% finished with the book, so perhaps my question will yet be answered, but throughout this feast I have been wondering occasionally and each time left unsure, despite earnest effort to conclude: does the book ever touch on Jacob’s wrestling with the angel?