Lord Arthur James Balfour: The Accidental Zionist Who Changed…Everything

From National Post columnist Barbara Kay

This essay has been lightly edited with a new preface and conclusion added. It previously appeared in it’s original version in the pages of the Dorchester Review.

By Barbara Kay (opinion columnist at the National Post since 2003)

Preface:

On June 17, the prestigious Munk Debates convened in a two-on-two format to debate the motion, “Anti-Zionism is Antisemitism.”

Arguing on the pro side were British author and journalist Douglas Murray, partnered with director of UK Lawyers For Israel, Natasha Hausdorff. On the contra side: MSNBC veteran and Hamas supporter Mehdi Hasan, with Israeli journalist Gideon Levy, anti-Zionist opinion columnist for the Israeli newspaper, Ha’Aretz.

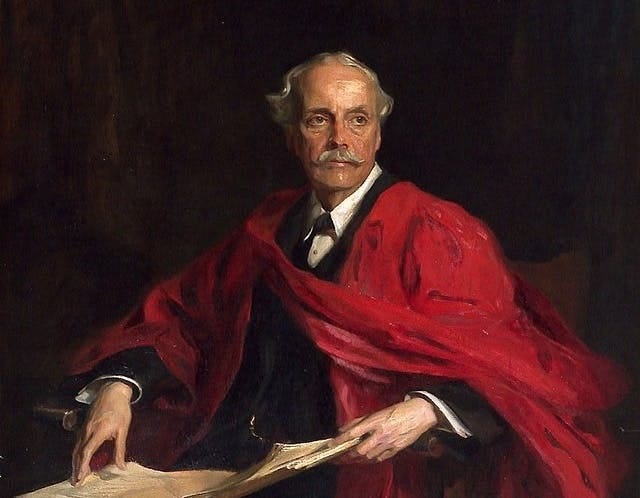

In his opening statement, Mehdi Hasan tried to brand Lord Balfour, of “Balfour Declaration” fame, as a "card-carrying antisemite," based on a few apparently damning words from Balfour, characterizing the Jews as an “alien and hostile” people. In her response, Hausdorff produced Balfour’s contextual words, “which [western civilization] too long regarded as alien and hostile,” words that not only exonerated him from the libel, but demonstrated his empathy for the Jewish people, and their long history of persecution, including in England.

When Hausdorff exposed Hasan’s duplicity, the audience gasped. It was one of the debate’s many pivotal and – for many Jews - gratifying exchanges. It isn’t often that we witness a lie conceived in antisemitism so vigorously and ineluctably exposed for all the world to see.

This moment of triumph for truth over mendacity seemed to me a good moment to share the fruits of my own curiosity about the man who – with his endorsement of “a national home for the Jewish people” – set in motion what many learned observers consider to be the greatest miracle of decolonization in human history.

I was less interested in his political career than in his personal qualities. Was he a good man? Maybe a great man? How did his contemporaries see him? Mostly, as I discovered, neither goodness nor greatness nor his peers’ opinions were relevant to Balfour’s Zionist legacy. He was a man of his time, his place, his Christian upbringing and the class system that put him in a position to follow his philosophical and political instincts whither they led without concern for the opinions of others.

Lord Arthur James Balfour: The Accidental Zionist Who Changed…Everything

The Balfour Declaration was one of the most consequential statements of modern history.

The Declaration was in fact a letter from Lord Balfour, writing as Foreign Secretary, and delivered to Walter Rothschild, 2nd Baron Rothschild, on Nov 2, 1917, for transmission to the Zionist Federation of Great Britain and Ireland. The pith of it reads:

His Majesty’s government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.

The text of the letter was published in the press a week later. And so it all began.

There was many a slip ‘twixt Declaration cup and statehood lip. But Israel did, for the third time in its history, become a state on May 14, 1948. Theodore Herzl said, “if you will it, it is no dream,” but will is not enough if great powers do not back the dream. Without Lord Balfour’s passion and determination to see the Jews return to their land, there would have been no Declaration, but more important no Mandate. For it was the Mandate that gave legal international standing to the Declaration.

But there would have been no passion and determination on Balfour’s part to begin with if he had not made the acquaintance of Chaim Weizmann, who would become Israel’s first president.

The wheels of that meeting were set in motion in 1902. The British Government, in which Lord Balfour served, had offered Zionist Jews land in East Africa (later Uganda) to found a national home, and it had been rejected. This was the moment when Balfour’s curiosity about the Jewish question was fully roused. I say “fully,” because the Jews had always interested Balfour. Balfour’s mother had instilled in him a solid belief in God, and a deep knowledge of Judaism’s sacred texts – the Bible, the psalms and the prophets. He particularly liked to read Isaiah aloud to his family, and according to his niece, Blanche Dugdale, who used to be amongst his audience, he read it “beautifully and reverently.”

And so it was that in 1906, when his government was defeated and he had more time on his hands, that he was open to a suggestion by his political agent, a Mr Dreyfus, to a meeting with Chaim Weizmann, heir to Theodore Herzl as the leader of the Zionist movement, and at the time an instructor in chemistry at Victoria University in Manchester, conveniently part of Balfour’s constituency.

This meeting, which was to last 15 minutes, famously lasted more than an hour, and has been well documented in Weizmann’s own memoirs and in the two-volume biography of Balfour written by Dugdale (Balfour himself left no memoirs). But it is such a good story it is worth retelling.

Weizmann had come to the meeting with no serious expectations. He described Balfour, sitting with his long legs stretched out in the languid pose that the cartoons made famous. Balfour told Weizmann the British gov’t was anxious to relieve Jews of their misery and asked why the Jews were opposed to the Uganda offer.

Weizmann (as described to Blanche Dugdale):

“I plunged into a long harangue on the meaning of the Zionist movement...that nothing but a deep religious conviction expressed in modern political terms could keep the movement alive and that this conviction had to be based on Palestine and Palestine alone. Any deflection from Palestine was – well, a form of idolatry. I added that if Moses had come into the 6th Zionist Congress when it was adopting the resolution in favour of the Commission for Uganda, he would surely have broken the tablets once again...

“I was sweating blood and trying to find some less ponderous way of expressing myself...Suddenly I said: ‘Mr Balfour, supposing I were to offer you Paris instead of London, would you take it?’

“He sat up, looked at me and answered: ‘But, Dr Weizmann, we have London.’

“’That is true,’ I said. ‘But we had Jerusalem when London was a marsh.’

“He leaned back and continued to stare at me...I did not see him again till 1916.”

By then, a decade later, England was in the midst of a world war, and Palestine – the region known as Palestine, that is, for no country of that name was yet envisaged – was acquiring great geo-political importance. What England’s role was to be in the area post-war would at that time preoccupy Balfour in practical rather than the philosophical terms that engaged him in his first conversation with Weizmann.

Weizmann’s emphasis on Palestine as a lynchpin of faith would have bewildered almost any other politician, but it was the right argument for Balfour. Mrs Dugdale wrote: “Balfour told me often about the impression the conversation made on him and how he understood from that time forward that the Jewish form of patriotism would never be satisfied with anything less than Palestine. The more he thought about Zionism, the more his respect for it grew.”

During the war, the acquaintance between Balfour and Weizmann was renewed and became intimate. When Balfour lay dying, Weizmann was the only friend outside his family circle admitted to see him. They did not speak, but Balfour moved his hand to touch the bowed head of his visitor.

Why was the aristocrat Lord Balfour, the social antithesis of this humble Jew from the Pale of Russia, so taken with Weizmann’s vision that he was willing to expend political capital and exert so much effort to see it realized? Who was Balfour? What was he?

Arthur James Balfour was born at his family seat, Whittingehame, in East Lothian, the “granary of Scotland.” A forebear had made a fortune in India in military materials, so he was financially secure for life, and socially connected at the highest levels.

Having lost his father when he was 7, Balfour was lucky in his mother, a strong-willed and educated woman who, according to Mrs Dugdale, inculcated the idea of duty as “the uncompromising foundation of his character.” He attended Eton and Cambridge, where he was described by a friend as “a man of unusual philosophy and metaphysics,” who could hold his own with the Dons (professors), “some of them men of undoubted genius.” He was devoted to his extended family, and much beloved by his nieces and nephews.

In his essay “Arthur Balfour: a Fatal Charm,”1 cultural critic Ferdinand Mount cites “nonchalance” as Balfour’s defining trait. Legendarily indolent, he rarely rose before 11 a.m., claimed never to read newspapers, and disdained the ritual schmoozing of fellow backbenchers expected by his peers in the Members’ Smoking Room. Mount says he was “indifferent to what his colleagues, the public or posterity thought of him or his policies.”

This loftiness – echoed in his unusual physical height - was perceived as admirable or maddening according to the observer and circumstances. Churchill said of him: “He was quite fearless. When they took him to the Front to see the war, he admired the bursting shells blandly through his pince-nez. There was in fact no way of getting to him.”

His self-sufficiency was no act. Sports-mad, he skipped lunch with the Kaiser to watch the Eton and Harrow cricket match, and when in Scotland might play two full rounds of golf a day (his handicap of 10 was better than P. G. Wodehouse and about the same as thriller writer Ian Fleming’s).

Balfour sounds from my description so far as if he was something of a playboy, but that is a very partial portrait. He was also known as “Bloody Balfour” for his readiness to endorse police action and his apparent indifference to their cost.

The Irish loathed him. In 1887 he became personal secretary for Ireland under his uncle, Lord Salisbury, just in time to enforce the Coercion Act against the volatile Irish Land League. Indeed, Balfour’s parliamentary critic William O’Brien saw him as a man who harboured a “lust for slaughter with a eunuchized imagination” who took “a strange pleasure in mere purposeless human suffering, which imparted a delicious excitement to his languid life.”

One hopes this accusation of actual sadism is an exaggeration of Balfour’s indubitable detachment. Yet indifference to human life is certainly not an uncommon charge laid against intellectuals for whom ideas loom larger in their claims to attention than the fate of those beyond their particular tribes.

For balance, we have Barbara Tuchman’s assessment:

“Balfour had a capacious and philosophical mind. Words to describe him by contemporaries are often “charm” and “cynicism”. “He had a profound and philosophic mind, he was lazy, imperturbable in any fracas, shunned detail, left facts to subordinates, played tennis whenever possible, but pursued his principles of statecraft with every art of politics under the command of a superb intelligence.”

Fortunately for his temperament, Balfour’s life circumstances had landed him at the centre of a genuinely intellectual circle. His brothers in-law, for example, were Lord Rayleigh, who became head of the Cambridge Laboratory and won the Nobel Prize for Physics, and Henry Sidgwick, the Cambridge philosopher who with his wife Elaine Balfour founded Newnham College.

Politically, Balfour enjoyed both dramatic success and dramatic failure. He led the Unionist Party longer than anyone before him since Pitt the Younger. And he was a minister longer than anyone else in the 20th century, including Winston Churchill. Balfour was the only Unionist who was invited to join Asquith’s first war cabinet, and continued as foreign secretary after the coup that brought Lloyd George to power.

As Churchill put it: “He passed from one cabinet to the other, from the prime minister who was his champion to the prime minister who had been his most severe critic, like a powerful, graceful cat walking delicately and unsoiled across a rather muddy street.”

One of Balfour’s teachers at Eton described him as “fearless, resolved and negligently great.” On the other hand, Mount tells us, “indecisiveness” was his bane. He would stand paralyzed in the mezzanine of his London home agonizing over which of the matching staircases to descend by. He could love - the great love of his life died after an unreasonably long engagement – but, allegedly too staggered by the loss of his almost-fiancée, he never married.2 He could not be pinned down politically on many issues, a matter of great frustration to his colleagues, and this cost him dearly. As Mount notes, his charm was indisputable, “but more than charm he would not give” and “in the end, the charm is all that remains.”

Balfour fought three general elections as party leader and lost them all. His premiership lasted less than four years and ended in a Liberal landslide in 2006, a great electoral humiliation in making him the only prime minister in the 20th century to lose his own seat. He did not seem greatly to repine at the rejection, though, and it is thanks to the loss that he had time to further his education on the Zionist movement.

Weizmann was by no means Balfour’s first Jewish friend. But he was his first Jewish friend from the other side of the Jewish tracks, so to speak. Balfour knew and socialized with the successful Jews of his generation, some of whom achieved high political honours. But almost to a man, they were assimilated Reform Jews and anti-Zionist, who had no objection to Uganda as a Jewish settlement. Balfour had to actively inquire about a meeting with the “other” kind of Jew to satisfy his curiosity.

As a man born to privilege and perfect cultural security, and like many other non-Jews very accustomed to the nationalistic fervor of the Arabs, the Greeks and the Poles, Balfour did not understand why his elite Jewish friends were so opposed to Zionism. He did not understand their passion for the perfect integration into their European homes they felt would seal their security. He did not understand what Ruth Wisse describes in her wonderful book Jews and Power as the politics of “complementarity” governing Diaspora Jewish attitudes, “whereby Jews tried to win protection by proving their value.”

One might think that a Jewish minister – the only one in the government at the time – would support a proposal on behalf of the Jews and Zionism, but the opposite turned out to be the case. Edwin Samuel Montagu, however, was vociferously opposed to Zionism and anything connected to it.

These were Montagu’s main reasons for opposing the Balfour Declaration:

“I assert that there is not a Jewish nation. The members of my family, for instance, who have been in this country for generations, have no sort or kind of community of view or of desire with any Jewish family in any other country beyond the fact that they profess to a greater or less degree the same religion. It is no more true to say that a Christian Englishman and a Christian Frenchman are of the same nation.

“When the Jews are told that Palestine is their national home, every country will immediately desire to get rid of its Jewish citizens, and you will find a population in Palestine driving out its present inhabitants”.

His concern was also for his own political future: “If Palestine will be the National Home of the Jews – all the voters in my constituency will tell me: “Go Home!!!”

When official negotiations with the Zionists began in 1916, anti-Zionist English Jews went into full attack mode. The Jewish Board of Deputies, who represented the “respectable Jews,” saw the Zionists as deluded, “an army of beggars and cranks.” One Jewish peer of the era wrote to her sister, “[Balfour} gets a great deal of information from Natty, naturally very one-sided,” referring to the first Lord Rothschild, Nathaniel, who had been converted to Zionism by Theodore Herzl, to his family’s great displeasure.

According to Tuchman, the bitter division between Zionist and anti-Zionist Jews resulted in the original words being softened and blurred, under the direction of Mr Edwin Montagu, to the point of leaving “unclear and forever controversial exactly what its drafters had in mind.”

One can see a contemporary parallel here in the bitter division, especially on our campuses, between pro and anti-Israel Jews. Today the battle lines are not drawn between assimilated Jews and those of more recent arrival from eastern Europe, and the stakes are not cultural acceptance or security. We are all accepted, we are all secure – or as much as Jews ever have been or can be. Today the battle lines are drawn ideologically. Those who identify as progressives understand that their acceptance and security in that movement is contingent on singling Israel out for denunciation as an occupying power. Those who don’t, see no conflict between their fidelity to Canada and their devotion to Israel.

In his memoirs Lloyd George remembers the Declaration as a reward bestowed upon Weizmann for Weizmann’s gift to the nation of acetone. Britain had used up her timber supply, which was its source of the wood alcohol necessary to the manufacture of cordite. Weizmann was mandated to find a substitute and did within a matter of weeks. This lucky coincidence brought him to London and into connection with policy makers.

Weizmann’s acetone work fell under the auspices of the admiralty, where Balfour was now first lord in Lloyd George’s government. When they met again, Balfour spoke to him as though it were only days rather than 10 years since they had last met, saying, “You know, I was thinking of that conversation of ours and I believe that when the guns stop firing, you may get your Jerusalem.”

But the Declaration was about a lot more than acetone. It had its origins chiefly in the hard facts around World War I geopolitics. England, France and Russia were at war against Turkey, whose neutrality they had assumed they had assured, but who had joined the Central Powers instead. When the Turks attacked the Suez Canal, the pivot point of the British empire in February 1915, the Middle East became the hottest of wartime hot spots.

Palestine was needed by the Brits for its strategic value, but they needed a strong moral case for seizing the initiative as well. In democracies, there always has to be a moral case. How much more so for taking possession of the Holy Land, an unusual acquisition unlike any other imperial adventure Britain had ever known.

In her book Bible and Sword, historian Barbara Tuchman writes: “The Balfour Declaration was issued to dignify that approaching moment, not only in the eyes of the world, but especially in the eyes of the British themselves.” It was necessary, she says, for the British conscience, for “[n]o advance in Britain’s imperial career was ever taken without a moral case.” Jerusalem was, after all, something quite other than Zululand in the eyes of the average English Christian.

Indeed, General Allenby was so moved by the moment of entry into Jerusalem that he dismounted outside the Damascus Gate so he could enter the Holy City on foot. Far from the Balfour Declaration being a kind of “propagandist gesture flung out haphazardly in wartime” as was bruited years later, that story, Tuchman says, “falls apart at a touch.” The Declaration was the real spiritual deal.

It took four years, but the Brits ultimately defeated the Turks and General Allenby went on to triumph not only in what would be Israel, but in Damascus, Aleppo and all of Syria. And now the Ottoman Empire was a pie to be carved up at will by the Allies. Now was the moment when both Jewish and Arab claims, both fermenting away for years, were to be reckoned with.

Britain had no policy other than to ensure her control over the area, and ensure France’s subordination. Negotiations went on at a furious pace, with T.E. Lawrence immersed with his fractious Arab Sheiks (Lawrence’s promises to his Arabs make a great story, but it is not relevant to Israel’s, because Lawrence’s interest was in Palestine east of the Jordan), and the Zionists beavering away in London. There were some 17 commissions of inquiry, weeks of parliamentary debate, endless newspaper commentary, but nothing solid emerged.

Luckily, Sir Herbert Samuel, the first High Commissioner for Palestine (and the first Jewish cabinet minister), found himself inclining toward Zionism, along with foreign secretary Sir Edward Grey and Lloyd George, then at the Exchequer (who was “very keen”). Grey warned that Britain should be careful not to agree to any plan that might be “inconsistent with the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine.” It is noteworthy that all these discussions were in terms of a “state,” not a “home.”

Meanwhile, C.P. Scott, respected editor of the Manchester Guardian, was facilitating meetings for Weizmann with Samuel and George and keeping the issue on the front burner (it was Scott who introduced Weizmann as a chemist to Lloyd George for the acetone project).

It was Sir Herbert Samuel who prepared the actual draft memorandum, “The Future of Palestine,” to the Prime Minister. Asquith did not like it. Samuel toned it down, but Asquith was still unhappy with it. Lloyd George liked it, but Asquith ascribed that to his determination to keep control of the Holy Land from “agnostic, atheistic France.” Actually he was wrong: Lloyd George liked its biblical resonances. In any case by December 1916 Asquith was out of power and Lloyd George was in, with Balfour as foreign secretary.

Here it should be noted that after the 1915 genocide of the Armenian people, Turkey was turning its attention to the 80,000 Jews in Palestine. Ten thousand Jews (including David ben-Gurion and Yitzhak ben Zvi) were exiled to Egypt with plans to destroy the rest of the community. Intervention from Germany and the U.S. put a stop to that plan, but one can assume that these events added urgency to the Declaration and influenced Woodrow Wilson’s firm support for the Mandate.

Not a word of the Declaration was arbitrary or casually inserted. Tuchman writes:

“The proposed Declaration was debated comma by comma, intermittently through the whole of 1917, to the accompaniment of anti-Zionist anguish, privately pleaded and publicly voiced.” As Winston Churchill noted: “Hardly any step was taken with greater deliberation.”

This wording was approved by Woodrow Wilson (before its adoption) and formal recognition given to it in 1922 under President Harding. France and Italy followed suit in February and May respectively of 1918.

The optimism around the Declaration can hardly be overstated. It was greeted with fanfare and high hopes for peace and an end to “the oldest of national tragedies,” as in the words of the Lord Mayor of Manchester, “The vision of the prophet Isaiah would be realized.”

Lord Robert Cecil said: “I believe it will have a far-flung influence on the history of the world and consequences which none can foresee on the future history of the human race.” He meant that in a positive way, and Weizmann’s cordial desert meeting with Feisal (the third son of Hussein bin Ali, the Sharif of Mecca) a few months later seemed to prove him right. The military governor Ronald Storrs, watching the people in Jerusalem wait to greet Sir Herbert Samuel, appointed as Palestine’s first high commissioner, said they were “almost faint with happiness” and “moving as if in the glory and freshness of a dream come true.”

T.E. Lawrence himself, although wholly devoted to his Arabs, was not averse to Zionism:

“I back it, not because of the Jews but because a regenerated Palestine is going to raise the whole moral and material status of its Middle Eastern neighbours.”

Even before the war was over, in 1918, a Mecca newspaper published an article under Sharif Hussein’s name, which urged the Arabs to welcome the Jews as brethren and to cooperate for their common welfare. Indeed, Weizmann visited Feisal at his desert home in Lawrence’s presence, where they reached a mutual understanding, later preserved in a written document, where the Emir agreed to “the fullest guarantees for carrying into effect the British government’s [Balfour] Declaration of November 2, 1917,” which included “all necessary measures to encourage and stimulate immigration of Jews into Palestine on a large scale.”

Feisal also sent a letter to the American Zionist delegates at the Peace Conference saying that Arabs and Jews “are working together for a reformed and revived Near East,” and that the Arabs wish the Jews “a most hearty welcome home,” that “there is room in Syria for us both” and that “indeed, I think that neither can be a real success without the other.”

When the Mandate was established, Britain intended to open up both sides of the Jordan to Jewish settlement. Alas, the Hashemites, Britain’s “client” overseen by Lawrence, failed to unite the Arabs, and leadership fell to Ibn Saud and his tribal allies from the interior of Arabia, who renounced the pledge.

And it was downhill from there. The purity of the Declaration moment could not be sustained. Britain partitioned Palestine contrary to its own policy as stated in the Balfour Declaration. Consequently, 75% of Palestine was assigned to the Hashemites in 1922 and Abdullah, another son of Sharif Hussein, became king of the freshly formed Emirate of Transjordan. The majority of Jordanites today still consider themselves Palestinian-Arabs living in what was Mandate Palestine.

But activism against the Declaration is useless, for the Declaration itself had no legal force. It was a policy statement that could be repudiated by a new government or allowed to lapse.

It was rather the Mandate that provided the basis in public law for the restoration of Israel in Palestine. The Mandate was an international engagement, signed and ratified by the Principal Allied Forces acting through the League of Nations, thus raising a mere statement of policy to the status of a treaty.

Talks went on. Sykes (of Sykes-Picot, which recognized French colonial aims in the Middle East), who was a brilliant political fixer, and might have created a working compromise, died of the flu at 40. And Weizmann famously defined the words “national home” as the opportunity for a Jewish nationality “which would be as Jewish as the French nation was French and the English nation English.”

The San Remo conference in April 1920 following the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 was meant to sort it all out. Due to unrest in Turkey it came into effect three years later, at which point Britain had been running things for three years. It was too late to return to a colonial protectorate and too early to reneg on pledges. At San Remo the Mandate stood as drafted with one exception: The British separated out Trans-Jordan from its terms.

The Mandate, which has no expiry date, was extremely precise about its conditions and purposes.

In the words of the preamble it was to “be responsible for putting into effect the Declaration originally made on 2nd November, 1917 by the government of His Britannic Majesty and adopted by the said [Principal Allied] Powers in favour of the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.”

There were 28 Articles, the primary one in Article 2 being to “place the country under such political, administrative and economic conditions as will secure the establishment of the Jewish National Home.”3

Four of the first seven articles deal with the position of the Jews; the remaining 21 articles are technical. The Arabs are not mentioned by name, rather as “other sections of the population” or as “various peoples and communities,” whose religious and civil rights and personal status were to be safeguarded.

As the Peel Commission concluded in 1937, “the primary purpose of the Mandate, as expressed in its preamble and its articles, (italics in original) is to promote the establishment of the Jewish National Home.”

The word “state” had been carefully sidestepped but “there was no question in anybody’s mind that this was what was eventually contemplated.”

In a 1920 press piece, Churchill foresaw “the creation in our lifetime by the banks of the Jordan of a Jewish state under the protection of the British Crown.” General Smuts saw “in generations to come a great Jewish State rising there once more.” At the time of the Peel Commission, there is no question but that the eventual establishment of a Jewish State was envisaged.

The Mandate was not a success, as we know. Its demise was assured from the moment when the total fiction of a dual responsibility toward Arabs and Jews alike was adopted. In 1939 a White Paper canceled further immigration and land purchase. Winston Churchill was disgusted:

“This is the breach, this is the violation of the pledge, this is the abandonment of the Balfour Declaration, this is the end of the vision, of the hope, of the dream.”

The question remains: Did Israel become a state because of or in spite of the British? The Declaration laid the foundation for the state, and then, because of circumstances and a failure of nerve, Britain ignored the logical follow-through of the project they had set in motion. The answer, says Barbara Tuchman, is both: “one of those unsatisfactory truths with which history so often defeats its interpreters.”

Balfour’s biographer Mrs. Dugdale reports that “near the end of his days [Balfour] said to me that on the whole he felt that what he had been able to do for the Jews had been the thing he looked back upon as the most worth his doing.” Tuchman wonders if he felt that “a special dignity attached to this one act out of all his life’s worth [of 50 years], when for a moment he had walked in the footsteps of the ancestral heroes of the Old Testament.”

As I became more familiar with the mindset of the man behind the Balfour Declaration, I came to understand why that first conversation with Weizmann resonated so deeply with him. Why were Jews then and now so divided about the idea of Israel regaining statehood? What is the unifying theme? I think it is because there are two basic perspectives on Israel. One is cultural and the other is existential. And they are incompatible.

The cultural, or social-justice school sees the Jews as one people amongst many, but one that has been singled out for persecution and in need of a refuge. These are the people, like former President Obama, who understand Israel’s rise to statehood as a response to the Holocaust. It was right and proper at that time for the world to reward Jewish suffering with a safe space for Jews. In Balfour’s day people with that view were happy to accept Uganda as that safe space. After all, if protection from persecution is the goal, what does it matter where the safe space is, as long as Jewish culture can continue to flourish.

The problem with the Obama vision – one shared by progressive Jews – is that it implies Israel’s legitimacy is contingent on Jewish behaviour. The threat of withdrawal of approval for that legitimacy is always in the air. Passing the Holocaust test – you suffered violence, you may not show violence to others – is always on the progressive mind. And in their opinion, Israel is failing that test.

The second school of thought is existential. For these Jews – think of Ze’ev Jabotinsky and David Ben Gurion – the central tenet is not cultural continuity, but nation-building. Nation-building does not seek legitimacy from others; legitimacy is inherent in a collective’s history.

When Balfour met Weizmann, he had only known Jews who embraced the first, cultural vision. Weizmann opened his eyes and heart to the existential vision. Balfour grasped it at once, and it excited him. That is no small thing. It led to the great promise.

That a promise was made for the restoration of sovereignty in our homeland by one of the most influential men in the world – not as a reward for acetone, not as a reward for suffering, not for any other reason than because Balfour recognized Jews as the indigenous people of the land we call Israel, and it was therefore historically and morally right that Jews reclaim that land - is the important thing, and for that reason his story should be known and his memory honoured in perpetuity.

Never, in my opinion, was his memory more appropriately honoured, or in a more fitting forum, or by more principled individuals than Douglas Murray and Natasha Hausdorff, than at the Toronto Munk Debates. It is a pleasure to report that they decisively trounced their opposition.

Thanks for reading. For more on the history of Israel, read The history of Jews, Palestinians and Israel - Part 1

Support Woke Watch Canada by upgrading to a paid membership:

Or, by contributing to our Donor Box:

Woke Watch Canada Essentials:

James Pew contributed a chapter to the best-selling book Grave Error: How The Media Misled us (And the Truth about Residential Schools). You can read about it here - The Rise of Independent Canadian Researchers

A long-form essay by Dr. M - Fulcrum and Pivot: The New Left Remaking of Toronto School Policy

For evidence of the ideological indoctrination in Canadian education, read Yes, schools are indoctrinating kids! And also, Yes, The University is an Indoctrination Camp!

Mount, Ferdinand, English Voices (2016), pp 358 ff

One suspects that even if May Lyttleton had lived, Balfour would have avoided marrying her on some pretext or other. There is no evidence that Balfour was a closeted homosexual, but he may have been asexual. He enjoyed an “amitié amoureuse” with (married) Mary Elcho for 30 years involving little or nothing in the way of sex, after which she wrote to him, I’ll give you this much, tho, for although you have only loved me little, yet I must admit you have loved me long.”

In 1922 the Mandate also recognized Hebrew as the official language of the Jews in Palestine. Hebrew was by then a spoken language for the first time in nearly two thousand years, “torn from biblical sleep,” in the words of the Israeli poet Yehuda Amichai.

“A national home for the Jewish people” is contrary to the expansionist designs of Islam, and, worse, the state of Israel is smack dab in the middle of a Muslim predomination. The Jews merit their own homeland, as do Kurds and Yazidis and others. But how does a small group resist Islamic fascism? I wish the world would focus less on Israel and more on the rights of minorities in Muslim-dominated dictatorships.

Apart from disagreeing with her conclusion, Barbara Kay presents an articulate and balanced presentation regarding the Balfour declaration. It is a well established fact that Balfour's declaration was heavily influence by Christian Zionism which foretold the second coming of Christ in a Palestine occupied by Jews. If we can accept that the Bible justifies Jewish appropriation of Palestinian land then we must also accept the conditions upon which this can occur:

"Ezekiel 47:21-23 “Divide up this land among the twelve tribes of Israel. Divide it up as your inheritance and include in it the resident aliens who have made themselves at home among you and now have children. Treat them as if they were born there, just like yourselves. They also get an inheritance among the tribes of Israel. In whatever tribe the resident alien lives, there he gets his inheritance.

It sound to me that the biblical authority for Zionism has somehow been lost in the fog of entitlement and greed and the peaceful inheritance promised by the prophecy has degenerated in the murderous onslaught of genocide.