By

(This post originally appeared in Michelle’s Medium website.)

The City of Quesnel, B.C. has voted unanimously to denounce the book “Grave Error: How the Media Misled Us (and the Truth about Residential Schools)” and to affirm their support for the findings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission was a “witnessing” process, not an investigative process. Some 6,000 participants stated their experiences at Indian Residential Schools in open public forums that traversed the country. Six thousand people is 4% of the 150,000 children who attended Indian Residential Schools over the course of 113 years. Is this representative of the full experience? Likewise, the 150,000 children who attended were only 1/3 of potential Status Indian students. Can all the ills of the present be solely blamed on Indian Residential Schools?

Were there positive experiences? Could adult caregivers have explained some issues — like why children’s clothing was taken, why numbers were assigned, why the children’s hair was cut and showers required upon arrival at school — all of which sound cruel and dehumanizing without context, such as that provided by Rodney Clifton, former residential school worker and co-editor of “From Truth Comes Reconciliation.”

Reportedly, the person in charge of gathering the recollections of former staff for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission had their budget cut from $100,000 to $10,000 and were told that their interviews would not be transcribed. These would have been the recollections of adults, which would have provided important historical context to the TRC reports.

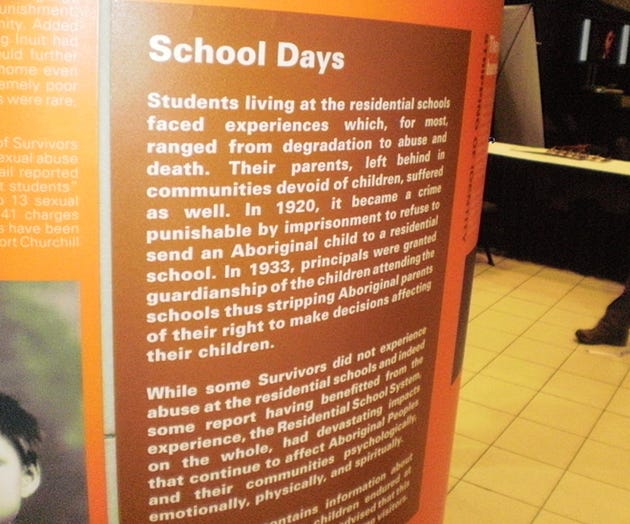

At the entryway to Truth and Reconciliation Commission sessions, a kiosk set a negative tone from the get-go, stating that “Students living at residential schools faced experiences which, for the most part, ranged from degradation to abuse and death.” This hardly suggested an impartial approach to individual reports or that positive comments would be well-received.

Kiosk at entry to TRC session.

Pauline Dempsey, daughter of Senator Gladstone and wife of Dr. Hugh Dempsey, curator of the Glenbow Museum wrote positively of her experiences at residential school.

In Terry Glavin’s book “Amongst God’s Own” about the Oblates of Mary Immaculate operated St. Mary’s Mission, a residential school near Mission, BC, one of the interviewees noted that all the chiefs in the area were all graduates of Indian Residential Schools; this had made them leaders. The book contains sad experiences as well as positive ones.

We are told that children are missing and even that some have been murdered, but there is no list of missing person’s names. The names listed on the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation banner include names of people whose deaths were completely unrelated to Indian Residential Schools or attendance at same — they include people who died of old age, people who died of tragic accidents far away from any Indian Residential School, alcohol poisoning and murder — as adults, not as children at school. To date, independent researchers have located and matched dozens of names of children who died at Indian Residential Schools to proper death certificates, in most cases signed by a parent or guardian, and in most cases, the child’s body was returned to their home reserve for burial there. It seems that families have lost the documentation about their loved ones, (some of whom died many decades ago; some who only became known to have existed to present day relatives due to exploring Ancestry.com, etc.) and this has inadvertently turned into an unproven international scandal that Canada committed genocide.

During the early days of Canada until about the 1940’s when modern medicines were developed, tuberculosis (TB) was the largest killer of ALL Canadians. Sometimes entire families were affected; many parents and siblings died. Many times children had ‘latent’ TB — meaning they were infected, but the infection was not active, no visible signs. If it became active while at school, that child would be sent to a hospital or sanitorium — so for the children in the school — their classmates ‘disappeared.’ TB treatments were months and often years in length. Thus, when the person returned to their family, they were a stranger to the family. It was as if the original person was gone.

Moffat et al (2013) in “Sanitoriums and the Canadian Colonial Legacy: The Untold Experiences of Tuberculosis Treatment” note that “within the context of TB, public health officials were granted the authority to coercively institutionalize the affected, forcibly removing infected individuals and placing them in sanitoriums (Shedden, 2011)”. Due to the long treatment periods, contact with family, culture and heritage was lost. One aboriginal testimonial in Moffat reads: “My brother went to the sanitorium and stayed there for seven years because he was allergic to the medication. It took seven years for the tuberculosis to go dormant. I never knew my brother. My older sister has no memory of him. My siblings never met their brother until he was thirteen. He was a total stranger. That’s the emotional part — that we had a brother we never knew.”

This kind of lack of historical context underlies the claims that people went missing at Indian Residential Schools. Since most of the present-day elders were children back then, what they remember is based on their childhood understanding of the world.

There are problems with relying on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission records as well. No part of this was a legal process based in evidence.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission occurred at the same time that Individual Assessments were being made for compensatory payments to individuals who claimed to have suffered harm at Indian Residential Schools. This was not a conventional legal process where an accuser would be forced to confront the accused and present provable evidence ‘beyond a reasonable doubt.’ An individual was able to meet privately with a small number of case reviewers, explain where they went to school and identify key individuals, perhaps even perpetrators of alleged physical, emotional or sexual abuse, and then the case reviewers adjudicated the financial compensation due. A named perpetrator was offered $2,000 if they wanted to try and defend themselves. There were few takers (as obviously $2,000 would not cover the cost of such defense), thus people in the Individual Assessment track may have been granted monies into the $200,000 range, on top of the $10,000 Common Experience payout that all attendees could access.

Behind the scenes, powerful law offices were happily enrolling Indigenous clients for class actions by sending them sign up forms that asked what body part had been inserted where, how many times, and by who.1

Many of these law firms have made millions of dollars.

However, in terms of legal due process, none of the statements made in the TRC or those made in the Independent Assessment Payment of the Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement have ever been proven in court.

Canadians have paid out or committed to paying out some $76 billion in related Indian Residential School, day school, day scholar, and child welfare claims — claims that for Indian Residential School (IRS) claimants, concern less than 150,000 people.

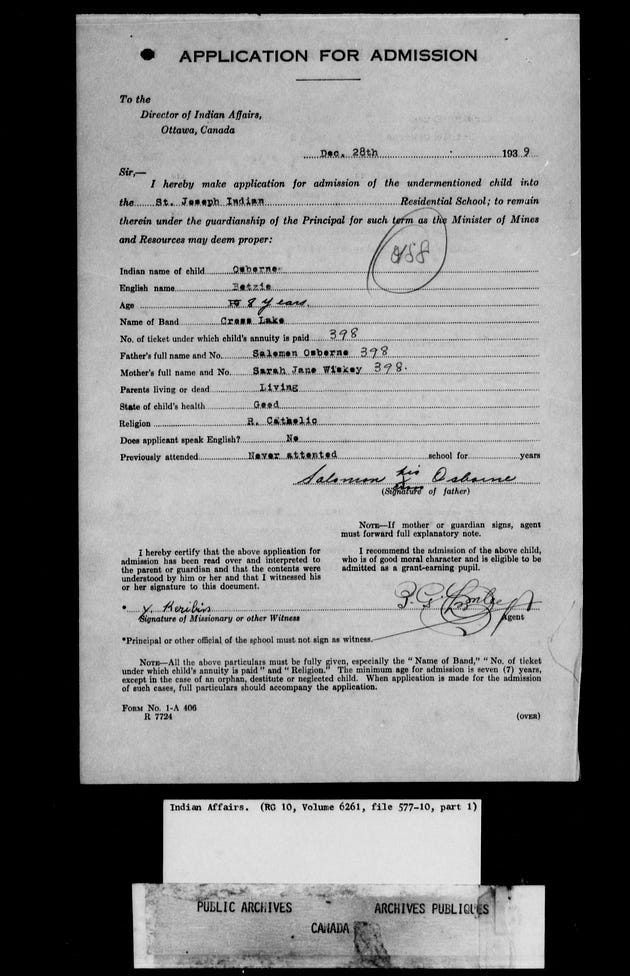

Most of the emotional trauma related to IRS is that which claims the children were all forcibly taken from their homes. This is untrue. Thousands of signed enrollment forms exist, signed by parents, who wanted their children to learn skills for the new world, and so enrolled their children in the future. No question that many children did not like the experience; many children sent to boarding schools also would have preferred to stay home with their friends and familiar things.

Application for enrollment for Betzie Osborne.

Likewise, many of the children ended up in Indian Residential Schools because this was the only available child welfare system to take up the many orphans or those from destitute or dysfunctional families. Of course that child’s sudden arrival at a residential school would have been shocking, especially if one or more parents had recently passed away. These ambiguous losses leave deep wounds.

In one example of a Blue Quills (Saddle Lake) story, the woman on camera explains that she and her sister were taken away in a big truck when she was six. She tells the interviewer that she had no say in the matter. This sounds terrible. She then goes on to say that she and her three siblings had been living with their grandfather, because both of her parents had died. Her grandmother had also died. She then says the grandfather was caring for nine others as well.

Even today, a grandparent would have a difficult time providing food, shelter, and clothing for 13 orphaned grandchildren. Residential schools took in thousands of orphans and saved their lives.

It was rare that Indigenous kinsman could take on orphans. Historically, Indian bands left orphans to fend for themselves, as detailed by the Grey Nuns’ diaries, in grisly detail. The bands were very happy that the Grey Nuns and Indian Residential Schools would take in the weak, the ill, the orphan, the developmentally handicapped.

This is well-documented by Robert Carney, historian and father of the more famous Mark Carney, past governor of both the Bank of Canada and England, and now UN climate czar.

If people can think back in history, up until about the 1940s, Canadians died of tuberculosis in great numbers — sometimes whole families were swept away by this incorrigible disease — “The captain of all men of death.” The excellent PBS documentary “The Forgotten Plague” shows the shocking impact that TB had on society in general (even though it addresses TB in the US). The documentary shows how TB sufferers moved west to warmer regions, looking for a healthier environment as a cure. This phenomenon also occurred in Kamloops where ultimately the King Edward Sanatorium was built. Dr. George Wherrett’s book “The Miracle of the Empty Beds” documents Canada’s efforts to cure TB, including extensive work to stop the TB epidemic in Indigenous communities.

Indeed, the husband of TRC Commissioner, Marie Wilson, Stephen Kakfwi, explains in his book “Stoneface” that most of his mother’s relatives had died of TB and that his mother was away at a TB sanatorium for six of the first twelve years of his life. This is why he ended up at Grollier Hall.

This context about TB (and later the Spanish Flu, which orphaned thousands of children as it hit young adults hardest) is only nominally reported in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and was glaringly absent from the previous Royal Commission on Aboriginal People’s report of 1996.

In addition to orphans, Indian Residential Schools were also a harbor for children from destitute or dysfunctional homes.

While there are many glowing memories of former students of residential schools who highlight how their lives had been wonderful on the trapline or on the trail with their communal family, as children, they have forgotten how many times the hunt was not successful, and how people often went hungry. This unpredictable nature of life on the land was precarious, to the point that parents back then often also enrolled their children in residential schools to provide the equivalent of “$10 a day” residential day care, knowing there would be food, shelter, and education, as opposed to hunger and deprivation. This also allowed parents to go to work and earn a living on the hunt or trapline without having to worry about caring for their children in extreme weather conditions.

And some families were violent or dysfunctional, even back then. If the RCMP or Indian Agent recognized or found a child at risk, the child or children were taken into care at Indian Residential Schools. This may sound patriarchal and racist on the surface, but when one reads the historical records of children found alone and hungry, with parents gone for days on a binge, it is clear that someone had to care for the children. There were no alternative care options.

A more contemporary story of this nature, which is well documented, is that of Richard Wagamese, who was a toddler of three, living in a communal tent camp with extended family. The adults went drinking in Kenora, ~96 km away. His mother was only 16 — just a teenager herself. After a few days, the children who had been left behind in the tent camp ran out of firewood and food and made their way to a local village where a police officer found them freezing near the post office. That began Richard’s life in foster homes — an unhappy experience — but one that he did survive. He later met his biological mother and spoke very highly of her, and she spoke highly of her residential school experience.

Canada has been accused of committing genocide when it was saving children’s lives and educating them, in a residential school process that had been agreed upon by Treaty Chiefs. While British Columbia was not party to the numbered treaties, thousands of parents willing sent their children to residential schools so that they could become capable in the new world. Perhaps the best example is Chief Dan George, who wept when he had to leave residential school at age 16 (this was the graduate age at the time) because he so loved learning.

That hardly sounds like genocide.

There are hundreds of stories of people who enjoyed their experience at Indian Residential School and found the education to be of great benefit to their lives. Robert MacBain’s book “The Lonely Death of an Ojibway Boy” (which upturns the myths about Charlie Wenjack’s tragic death) shows how much the children loved the people who ran that school, sending them letters addressed to the principal and his wife as “Mom and Dad” and signed “With Love…”

By contrast to the claim of ‘cultural genocide,’ several of the Oblate fathers, who were highly educated men, created syllabic ‘alphabets’ and documented Indigenous languages which had only been oral languages until then, and would have disappeared without the Oblate’s diligent work. Likewise, the children were sent to schools that were operated by the Christian denomination that the parents had already adopted, often decades earlier, as is clear in the story of Rose Prince, whose parents attended Williams Lake Indian Residential School. The parents wanted their children to be raised with teaching related to their chosen faith.

Claims have been made of children being murdered by priests, nuns or other clergy, but no such evidence has been presented, nor have such claims been proven in any court. The alleged discovery of 215 unmarked graves at the former Kamloops Indian Residential School happen to lie along the line of a former septic field trench, according to previous land use records. It is a tragedy that wild publicity related to these claims was broadcast around the world before any formal confirmation could be made. Canadian society is now disheartened, demoralized, and split over the disinformation that was distributed.

This ghastly news from the Kamloops band of a ‘mass grave’ and purported ‘genocide’ led to the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP) legislation being rapidly pushed through the Canadian parliament a month later, in a paroxysm of unwarranted guilt. The legislation had been stalled as six provinces had wanted further consultation which was difficult to achieve during COVID lockdowns at the time. There was no proper evaluation of what UNDRIP would mean for Canada’s future. Likewise, the day after UNDRIP passed, China accused Canada of genocide at the UN, citing the Kamloops claims, creating international challenges for us.

Death certificate for Bobby Joseph Bell. Signed by his mother.

The death records of the children who died while attending Kamloops Indian Residential School, and other BC schools (most of the deaths being off-site and due to accidents or tragedies like a home fire, and thus unrelated to the school per se) are listed here.

Undoubtedly some children who went to Indian Residential Schools did have a terrible time. And they have been financially compensated for it, without having to go through a court trial to prove anyone’s guilt. This is a rare privilege in our contentious society which has not been afforded to any other party in Canadian society.

Some First Nations people continue to claim that thousands of children died at Indian Residential Schools without ever looking at the provincial death records (example above). People claim that thousands of children are missing, but there is no list of names of missing children; no missing persons claims over 113 years of the school operations that were not resolved. As noted in the Fifth Estate documentary about Buffy Ste. Marie, which suggests she is a ‘pretendian,’ Status Indians and attendees at Indian Residential Schools were extremely well documented.

It is crucial that open, civil debate continue on this topic. The crisis in Quesnel should be a means to opening a door to dialogue on these distortions of history; not a call for censorship.

Some people are obviously getting rich from the sorrows of others, and many of our children are suffering and literally dying for lack of attention to the LIVING CHILDREN who are now being taught to hate their heritage and their country and fellow citizens, based on claims made without historical context. This is hateful. This is a crime against humanity. Every living child matters most of all.

Michelle Stirling is a former member of the Canadian Association of Journalists. She researched, wrote, and co-produced historical shows about Southern Alberta under the supervision of Dr. Hugh Dempsey, then curator of the Glenbow Museum. She also researched and co-wrote a documentary on genocide; the factual content so dark the producer decided not to release it.

___

Thanks for reading. For more from this author, read Don’t They Teach Historical Context at School Anymore?

BREAKING NEWS:

A new long-form essay by Dr. M - Fulcrum and Pivot: The New Left Remaking of Toronto School Policy

James Pew has contributed a chapter to the new book Grave Error: How The Media Misled us (And the Truth about Residential Schools). You can read about it here - The Rise of Independent Canadian Researchers

Also, for more evidence of the ideological indoctrination in Canadian education, read Yes, schools are indoctrinating kids! And also, Yes, The University is an Indoctrination Camp!

There are now two ways to support Woke Watch Canada through donations:

1) By subscribing to the paid version of the Woke Watch Canada Newsletter for - $7 Cdn/month or $70 Cdn/year

2) By making a contribution to the Investigating Wokeism In Canada Initiative, which raises the funds necessary to maintain and expand Woke Watch Canada’s research and investigation into Dysfunctional Canadian School Boards, Education, Indigenous Issues, Free Speech, and other areas of Illiberal Subversion and the Canadian Culture Wars.

The 6,000 people who told their stories to the TRC had all attended residential schools in the post war years when binge drinking virtually captured most western and northern indigenous communities. Particularly from the late 1950s through the 1970s entire communities succumbed to binge drinking. This meant that thousands of children were living in completely dysfunctional homes. Sexual abuse and other pathologies are inevitable in such an environment. By the 1960s many of the residential schools were mainly used as placements for these extremely damaged children. The children from stable homes were housed in dormitories with these damaged children. Sexual abuse was the result. There was a great deal of sexual abuse in the schools, but as historian Jim Miller says, it was student on student abuse. There is no evidence that the number of pedophile priests and teachers was any higher in residential schools than at any other schools. The TRC spent zero time on examining the child welfare factor at residential schools. This is scandalous, because it is impossible to understand residential schools without understanding the child welfare factors

Fabulous article. Should be in every newspaper in Canada.