Residential School Recrimination, Repentance, and Reconciliation

An Essay by Anthropologist, Hymie Rubenstein

By

By far the oldest, largest, and most influential Christian community in the world is the Roman Catholic Church.

Founded on the Jewish notion of showing remorse for and turning away from sinful behaviour, repentance is a key stage in Catholic salvation.

In the New Testament, John the Baptist called for repentance during his sermons, as did Jesus when he proclaimed the Gospel for Salvation.

Rooted in recrimination from Indigenous people, repentance, including verbal self-flagellation, now marks the Church’s involvement with Indigenous people, especially its 113-year association,1883-1996, with Canada’s government-funded Indian Residential Schools

At their height around 1930, this residential school system totaled 83 institutions, though there were 142 such institutions that opened and closed over the years. The Roman Catholic Church operated 43% of the schools, the Anglican Church 25%, the federal government 16%, the United and Presbyterian Churches 13%, Mennonites 2%, and Baptist 0.6%.

Various Catholic orders of priests and nuns administered schools attended by the largest cohort of Indigenous children out of the 150,000 children the federal government says were its students.

For this and other reasons, the Catholic schools have received the most media and other attention.

One of these other reasons is that former students and their supporters have spoken often of horrendous abuse at the hands of residential school staff: physical, sexual, emotional, and psychological.

They have also condemned that the residential schools provided Indigenous students with a second-rate education focused primarily on prayer, elementary literacy, basic numeracy, manual labour in agriculture, light industry such as woodworking, and domestic work such as laundry work and sewing. Harsh physical punishment such as caning and strapping are said to have been the order of the day.

These complaints never mention that many of these features also characterized Canada’s rural public up to World War II or later.

Nor is it ever acknowledged that attendance at these residential schools was entirely voluntary until 1920 and rarely enforced thereafter or that about half of all students who attended between the 1880s and 1950s dropped out after Grade 1 and that few students made it as far as Grade 5, hardly enough time for Indigenous cultural destruction, another criticism long made by Indigenous leaders and activists.

Complaints from students about their treatment and lobbying by Indigenous leaders led to a quasi-penitential Indigenous apology at the Yellowknife Airport in the Northwest Territories in 1984 where Pope John Paul II delivered a statement that only fleetingly mentioned the “faults and imperfection” of his Church’s treatment of Aboriginal people. Instead, most of his address was full of glad tidings fundamentally contrary to the current thoroughly negative narrative, but one supported by a large body of evidence going back to first contact between the church and Canada’s Indigenous people beginning in the early 17th century:

“I know of the gratitude that you yourselves, the Indian and Inuit peoples, have towards the missionaries who have lived and died among you. What they have done for you is spoken of by the whole Church; it is known by the entire world. These missionaries endeavoured to live your life, to be like you in order to serve you and to bring you the saving Gospel of Jesus Christ.

“Whatever faults and imperfections they had, whatever mistakes were made, together with whatever harm involuntarily resulted, they are now at pains to repair. But next to this entry, filed in the memory of your history, is the record, with endless proofs, of their fraternal love.

“That marvellous rebirth of your culture and traditions which you are experiencing today owes much to the pioneering and continuing efforts of missionaries in linguistics, ethnography and anthropology... Yes, dear Indians and Inuit, the missionaries have always shared in your cultural and social life.”

Twenty-four years later the Assembly of First Nations (AFN), Canada’s largest Aboriginal lobby group, made a plea for reconciliation with the Catholic Church at a plenary assembly of the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops. In his October 2008 address, AFN Chief Phil Fontaine said he hoped the Church could use its influence and experience to help lift Indigenous people out of poverty, acknowledging that in the past Aboriginals and the Church had accomplished much good together, despite what he called the legacy of hurt at Indian Residential Schools.

“I believe the Catholic Church has a significant role to play in helping us pave the way to something absolutely better,” he said, adding Indigenous people did not need the Catholic Church for its money, but for its influence, experience, and commitment.

“You understand us as well as anyone in this country,” he said, noting the Church knows “what is important to us and where we want to take our communities.” [emphasis added]

This was followed by the second papal apology for the church’s role in the schools’ day-to-day operations. In April 2009, Pope Benedict XVI invited a Canadian delegation, made up of representatives of Indigenous communities, as well as Catholic dioceses and religious communities across Canada, to a private meeting at the Vatican to discuss their experience of residential schools. During this meeting, the Pope listened to their stories and expressed his regret and sadness for the sorrow suffered by many Indigenous people in the residential school system. However, he refrained from formally apologizing for his Church’s role in Canada’s policy of Indigenous assimilation and residential schooling.

A third statement of repentance came from the Canadian Council of Catholic Bishops on Sept. 24, 2021:

“We, the Catholic Bishops of Canada, gathered in Plenary this week, take this opportunity to affirm to you, the Indigenous Peoples of this land, that we acknowledge the suffering experienced in Canada’s Indian Residential Schools. Many Catholic religious communities and dioceses participated in this system, which led to the suppression of Indigenous languages, culture and spirituality, failing to respect the rich history, traditions and wisdom of Indigenous Peoples. We acknowledge the grave abuses that were committed by some members of our Catholic community; physical, psychological, emotional, spiritual, cultural, and sexual. We also sorrowfully acknowledge the historical and ongoing trauma and the legacy of suffering and challenges faced by Indigenous Peoples that continue to this day. Along with those Catholic entities which were directly involved in the operation of the schools and which have already offered their own heartfelt apologies, we, the Catholic Bishops of Canada, express our profound remorse and apologize unequivocally.”

A third papal statement of contrition came during current Pope Francis’s six-day July “penitential pilgrimage” to Canada, July 24-30, 2022.

In his July 25 address on the grounds of the old Ermineskin Indian Residential School at Maskwacis in central Alberta, Pope Francis said:

“I recall the meetings we had in Rome four months ago. At that time, I was given two pairs of moccasins [representing the bodies of missing children] as a sign of the suffering endured by Indigenous children, particularly those who, unfortunately, never came back from the residential schools.… It is necessary to remember how the policies of assimilation and enfranchisement, which also included the residential school system, were devastating for the people of these lands. When the European colonists first arrived here, there was a great opportunity to bring about a fruitful encounter between cultures, traditions and forms of spirituality. Yet for the most part that did not happen. Again, I think back on the stories you told: how the policies of assimilation ended up systematically marginalizing the Indigenous peoples; how also through the system of residential schools your languages and cultures were denigrated and suppressed; how children suffered physical, verbal, psychological and spiritual abuse; how they were taken away from their homes at a young age, and how that indelibly affected relationships between parents and children, grandparents and grandchildren.

“In the face of this deplorable evil [cultural destruction and forced assimilation], the Church kneels before God and implores his forgiveness for the sins of her children.” [emphasis added]

A fulsome papal apology, if there ever was one, full of remorse about what should have been a “fruitful encounter” between belief systems but instead represented “spiritual abuse” of children in the boarding schools, a metaphor for one rooted in contemporary moral relativism asserting that the gospel of Jesus Christ has no higher standing than traditional Indigenous spirituality, part of a statement damning the entire Church and its 2,000-year-old mission in the process.

Implicit in Pope Francis’s penitential address is that a multiplicity of pre-contact polytheistic Indigenous spiritual systems are morally and supernaturally equivalent to Catholicism’s fundamental beliefs: that Jesus is the Son of God and equal to God; that He was crucified to pay the penalty for all human sins; that He rose from the dead; that all humans are saved by the grace of God; and that salvation and the inheritance of the Kingdom of God can be achieved only by a deep belief in these core principles and the renunciation of any contrary anti-Christian ones.

None of these declarations of repentance acknowledged that as the decades passed more and more Indigenous students arrived at the schools already burdened with the sorrows, abuses, and traumas said to have been implanted by their school experience.

Using a wealth of archival data, Greg Piasetzki has recently argued that:

“As painful as it may be to admit today, the vast majority of native children attending residential schools during the post-war period suffered from social ills, family hardships and health concerns that were far more serious than those faced by most other children in Canada. In particular, the devastating inter-generational effects of alcoholism and parental dysfunction on reserves had turned residential schools into a de facto native child welfare system. Had the government shut these schools down in the 1940s, as it very much wanted to, those children would have been left at grave risk of injury or death. There was, quite simply, no other place for them to go.”

By 1975, for example, children from “broken or immoral homes” constituted nearly the entire student population at three Saskatchewan residential schools: Gordon’s Residential School (83%), Muscowequan Residential School (64%) and Cowessess Residential School (80%).

As Piasetzki asserts:

“This near-complete takeover of residential schools by high-needs children, many of them likely suffering from undiagnosed FASD [Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder], would have made the experience for all students extremely difficult, especially the minority who were attending only because there was no day school near their home reserve. This likely explains the negative experiences of so many residential school students.”

In celebrating a progressive lurch to the left that says all spiritual beliefs have equal validity or that even pagan ones are more authentic, Pope Francis and the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops before him surely tarnished their legacy while defaming the memory of the thousands of priests, nuns, Catholic brothers, and lowly workers, many of them Indigenous people, who gave a lifetime of work compassionately and patiently teaching and caring for tens of thousands of Indigenous children, nearly all with their parents’ or the state’s blessing, all in the name of their God, so they could adapt to life in a rapidly changing Canadian society.

Pope Francis seemed willfully ignorant of or indifferent to such considerations. Neither did he show any awareness of how few children were Indian Residential School students and for how long: that only one-third at most attended for an average of 4.5 years. Nor did he address whether there was any alternative to the residential, or the equally maligned Indian Day Schools, during their 150 years of operation beginning in the mid-19th century. Surely, that alternative was no Western education, partly because there was much more demand than supply as the decades passed.

Unlike his predecessor, John Paul II, Francis made only fleeting and heavily qualified acknowledgement of the “fraternal love” and lifetime of devotion and sacrifice thousands of priests, nuns, and school employees showed in their noble attempt to enable Indigenous children to adapt to the inexorable economic and technological transformation going on in Canada since the mid-19th century when he said, “Although Christian charity was not absent, and there were many outstanding instances of devotion and care for children, the overall effects of the policies linked to the residential schools were catastrophic.”

As for the role of the state in this catastrophe, if the legal recognition of Indigenous people had not occurred – if there had been no Royal Proclamation of 1763, no land treaties, and no Indian Act – would not most Aboriginals have long been fully absorbed by the millions of immigrants from more developed Western European counties who began flooding into Canada from the mid-19th century? Instead, the ethnic identities of Canada’s first peoples were legally protected as were their languages and cultures even in the residential schools. This prevented any “cultural genocide” — a politically hyperbolic rendering of ordinary enculturation — while being exposed by dedicated Christian missionaries, mostly Roman Catholic, to those features of modernization such as literacy, commercial agriculture, carpentry, and other vocations it was hoped would allow them to prosper in a rapidly changing country.

Conversely, if the enculturation – internalization of features of alien cultures – of Indigenous people had not been encouraged, is there reason to believe that they would now be far better off pursuing a traditional stone-age existence lacking literacy, Western technology, modern medicine, Christian teachings, and other fruits of post-Neolithic culture?

Despite the role the Catholic Church played in encouraging these practices to compensate for the loss or decline of traditional livelihood strategies like hunting, gathering, subsistence farming, trapping, and bartering, the Pope’s broad, albeit distorted, apology did not prevent Murray Sinclair, former Chief Commissioner of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) charged with reporting on the operation and legacy of the Indian Residential Schools, from dismissing the apology as inadequate by claiming that it, “… left a deep hole in the acknowledgement of the full role of the Church in the Residential School system, by placing blame on individual members of the Church,” a wildly false assertion given the Pope’s confession that “the Church kneels before God and implores his forgiveness for the sins of her children.”

Note also that each of these papal and bishop apologies for the same involvement with Indigenous people has been more fulsome and contrite than the previous one even though the historical facts remain the same.

Equally important, how can John Paul II’s and Pope Francis’s incompatible versions of the Catholic Church’s interaction with Indigenous people be reconciled, especially coming from two men whose moral opinions are said to be infallible because they are divinely inspired?

Apart from the fact that Pope Francis is a liberation theologian for whom a New Age social gospel trumps the age-old personal salvation one and that Pope John Paul II was a stern critic of Marxist-based liberation theology, the most straightforward answer is that they can never be reconciled because the traditional one is based on western-style rationality and recorded historical reality going back centuries, while the current one was made known just as the last Indian Residential School closed in 1996 and is rooted in pre-scientific Indigenous myth-making, mass hysteria, and financial demands.

Anyone trying to dispassionately understand the historical record of the Church’s dealings with indigenous children while the Indian Residential Schools were still in operation, not decades later when over $3 billion was paid out to former students for vilifying them with lightly examined claims, will find that, “Whatever faults and imperfections they had, whatever mistakes were made, together with whatever harm involuntarily resulted” were overwhelmed by “the fraternal love of” Indigenous people and much admiration for indigenous culture and traditions.

This fraternal love of Indigenous children is most clearly revealed by the actions of the Roman Catholic Sisters who lovingly taught and nurtured the indigenous children at residential schools. These nuns kept detailed records of daily events which were periodically forwarded to the mother houses of their religious orders.

Similar records, called codices, were kept by the Oblates of Mary Immaculate at their missions across Canada, many of which had residential schools.

Most of these chronicles were sent to the TRC years ago in response to its requests for records from religious orders across Canada, but the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, the lavishly funded body that is continuing the work of the TRC, has not digitized them for its archives, and they are thus not available to the public.

Fortunately, the chronicles of the Sisters of Providence at Cluny, Alberta, the Sisters of Charity (Grey Nuns) at Cardston, and the Sisters of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin at Delmas, Hobbema, and Onion Lake, and the codices of the Oblates at these missions were deposited by the Oblates at the Provincial Archives of Alberta where extensive excerpts were recently transcribed and translated by Eloi DeGrace and are now available on the Indian Residential School Records site.

The staff chronicles of the Sisters of Charity of Our Lady of Evron Mission St-Raphael - Le Goff, Alberta, for example, contains entries like the following ones:

“June 4, 1916 -- The next day, Sunday, June 4, all the Indians came to attend High Mass; the church was full. All sang at the services; they pronounced Latin quite well, recited the Rosary in Montagnais; the hymns were also mostly in that language.”

Montagnais was the Indigenous language spoken by most residential students at Le Goff. This is just one of many instances that demonstrate that a blanket prohibition on indigenous languages across the IRS system is simply not true.

“July 30, 1916 - pages 13-14 On July 30, the school was closed; typhoid fever had already claimed 10 victims among the children. The Sisters, during the whole time that the epidemic lasted, made numerous visits to the sick scattered on the reserve. Their rounds were sometimes quite long. It was during these excursions that they got to know the faith, the good spirit, the confidence in the priest or the Sisters of their dear Montagnais, their sensitivity to signs of affection and devotion. But also, they were more than once able to observe the uncleanliness, the disorder of their grown-up children of the woods, their carelessness and little care for their sick. The little authority that the parents exercise over their children in general.”

Repeatedly, the pages reveal that IRS students were permitted, even encouraged, to speak their native languages.

The many detailed accounts of those who ran the residential schools were not deemed important enough to be documented in the TRC Report or in the reports now being produced by the NCTR.

On the “student activities” page, there is historical information that totally debunks the IRS genocide narrative. We are told of many field trips of former IRS students, like those in a dance troupe that traveled to Mexico City to compete in 1964 or of groups of IRS students who attended Expo 67 in Montreal:

“Students from several schools, including Kuper Island and Marieval, travelled to Expo ’67.

Many schools had bands and choirs, and some offered individual music lessons. A number of radio programs were recorded featuring the children singing in both English and Cree.

“In the early years, schools bought radios and phonographs for the students’ entertainment during the long winter evenings. In later years there were games, movie nights, dances and parties.”

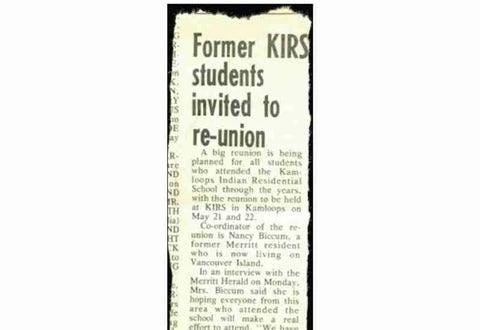

One page is dedicated to “School Reunions,” including the one held in 1977 to commemorate the now notorious IRS at Kamloops, British Columbia.

Over 280 former students and staff attended the reunion from towns and cities all across British Columbia. Among them were Canada’s first status Indian Member of Parliament and former Kamloops Indian Residential School student, the Hon. Len Marchand; the Reverend Adam Exner, Bishop of Kamloops; Kamloops physician Dr. Ivan Smillie; Chief Victor Adolph of the Fountain Band and Chief Harvey McLeod of the Upper Nicola Band.

Many former staff also attended – former Oblate principals Bishop Fergus O’Grady, Father Gerald Dunlop, Father Allan Noonan, and indigenous administrators Nathan Matthew and Ken Manuel; several members of the Sisters of St. Ann, and other former teachers and staff members, both indigenous and non-indigenous, including indigenous teacher Benjamin Paul, Arnold Poelzer, and Brother Murphy.

According to the Merritt Herald, the reunion was held at the school on the weekend of May 21 and 22.

Events included Indian dancing with Ernie Philip; slides of the “good old school days” presented by Father Noonan “where many of the students will recognize themselves”; more slides presented by former Indigenous teacher Benny Paul; “Bone Games” and a salmon barbecue and dance.

The guest book, filled with more than 280 signatures, was prefaced it with this inscription:

This simple booklet will contain the names of people who chose to come together out of sentiment to meet with each other, to reminisce, and perhaps to mark the near-end of an institution which represented a significant historical era in the lives of Native Indian People….

Today, the Kamloops IRS is seen as a place where 215 children were tossed into a mass grave after being murdered by its priests and nuns.

The enormous body of historical evidence in Green’s website also reveals no evidence of any missing, neglected, or murdered children. More particularly, it fundamentally contradicts the currently fashionable but totally false genocide trope: how is it possible that an educational system freely embraced by most indigenous people could be called genocidal when it offered field trips, phonographs, dance troupes, sports clubs, native languages and customs, ice rinks, swimming pools, all exclusively for its students?

Much of the TRC material is based on interpretations and recollection gathered decades after the last schools closed from a highly selective cohort of former students with an axe to grind or pockets to line.

Which is more credible?

There is no denying that European contact and colonization contributed to profound changes in Indigenous cultural and social life, including legal prohibitions of practices like polygamy, slavery, the purchase of wives, torture, and for many years, the potlatch. But neither the Catholic Church nor the schools its orders operated forcibly and genocidally assimilated Indigenous people into accepting a Euro-Canadian Christian identity.

To be sure, Catholic missionaries were, by their calling, engaged in proselytizing. Their methods, however, were neither forcible nor absolutist. There were no forced conversions or baptisms.

The residential schools are presented as the primary instrument of a policy of “forced assimilation” based on universal attendance. But most Indigenous children never attended a residential school despite the former head of the TRC, Murray Sinclair’s declaration to the United Nations in 2010 that, “For roughly seven generations nearly every Indigenous child in Canada was sent to a residential school. They were taken from their families, tribes and communities, and forced to live in those institutions of assimilation.”

As already mentioned, fewer than one-third of school-age “Status Indian” children, and an even smaller proportion of the general population of Indigenous children, ever attended a residential school. Most children attended on-reserve day schools or, in later periods, integrated provincial schools. But attendance at day schools was abysmally low, and before the mid-20th century, as many as one-third of Indigenous children did not attend any school at all, the greatest tragedy of all.

In 1920, the federal government tried to bring the Indigenous population into compliance with provincial compulsory attendance laws through an amendment to the Indian Act. But the amendment did not require attendance at a residential school as such. Instead, it said, “Every Indian child between the ages of seven and fifteen years who is physically able shall attend such day, industrial or boarding school as may be designated by the Superintendent General ... Provided, however, that such school shall be the nearest available school of the kind required.” The Canadian compulsory school attendance laws were only loosely applied in the case of Indigenous children, with forced attendance at the residential schools occurring primarily in cases of neglect or abuse in the home.

As for the forced assimilation and cultural suppression posited by Pope Francis, the residential schools were committed to integrating indigenous and “Canadian” cultures, not eradicating indigenous cultures, a well-known and universal process called enculturation. The 1937 Indian Affairs Annual Report states, “Consideration has been given to ways and means whereby the Indian population can be encouraged to conserve still further their ancient values and skills and thus contribute to the cultural life of the nation.”

To this end, the residential schools aided the survival of innocuous Indigenous traditions by incorporating traditional music, dance, and art into classes and school activities. The Indian Affairs reports and other sources are replete with examples of the residential schools’ encouragement of Indigenous cultural expression, including the following tiny sample:

At the Cluny, Alberta school in 1938, students dressed in beaded costumes danced to the rhythm of Indian drums and war songs to an audience of over 300.

In 1963, the school at Cardston hosted a troop of Blackfoot actors who showed a film on Blackfoot life in the early days, followed by a pageant depicting Blackfoot traditions and featuring a Sun Dance.

The choir from the Portage La Prairie school sang in English and Cree at Expo ‘67 in Montreal.

In the 1950s, the Gordon’s School in Saskatchewan established a powwow dance troupe that travelled extensively in Canada, the United States and several European countries.

As for the charge of physical genocide, there is not a single verified murder of any student at any residential school during their 113-year history.

Yet some activists, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, have employed an extraordinarily expansive definition of genocide to imply mass atrocities took place at the schools. Others have alleged, with no credible evidence, that the schools practiced physical genocide through purposeful neglect and abuse and in some cases, even homicide. But the historical evidence shows that the opposite was true because the schools actively and compassionately promoted the physical well-being of the students.

For example, by mid-20th century, the residential schools significantly reduced the scourge of tuberculosis that ravaged reserve communities through a comprehensive vaccination program. And while residential school death rates were substantially higher than in the general Canadian school-age population in the early decades of school operations, by the mid-20th century, they were virtually equal.

Many residential schools also served as medical centres for surrounding communities to prevent and treat trachoma and other conditions in the Prairies in the 1930s. Rural schools in Canada were described at a 1919 Dominion Council of Health meeting as “not fit to raise swine in,” and as having inadequate heating and lacking playing areas. By comparison, most residential schools early on provided indoor and outdoor facilities for sports and exercise. In 1898, the Kuper Island School in 1898 built a “new gymnasium … [which] proves to be a very useful addition to the school, for besides giving opportunity for athletic and calisthenic sport, it is supplied with a permanent stage which makes it of great value for receptions and entertainments.”

At the Blood school, there was “Recreation three times a day after each meal, football, swimming, fishing, shooting with bows and arrows…Boys and girls each have their own playgrounds, and are always under the supervision of an attendant.”

Throughout the residential school era, particularly after World War II, residential school teams won numerous local, national and international championships in hockey, boxing, lacrosse, cross country skiing, and other sports. Although school administrators sometimes submitted complaints to Indian Affairs about the lack of funds to improve recreational facilities, the many sports successes could not have been achieved had the players not had access to good sports facilities and equipment.

Catholic run residential schools also implemented the rigorous nutritional standards set by the Canadian government in the 1950s. The health benefits to the students were long-lasting. Research has found that residential school students were taller and less obese as adults than would have been the case if they had attended other kinds of schools. The residential schools also attended to students' nutritional needs in earlier periods. The 1925 Indian Affairs Annual Report states, “Milk herds are being tested [there was a concern broadly in Canada about diseases carried in milk] and the children's diet at these institutions carefully controlled. In the prairie provinces, travelling nurses visit Indian schools regularly to this end. The department is co-operating with the Canadian Junior Red Cross in the promotion of better health for Indian children.” The Department of Indian Affairs noted in its 1944 report that in outlying districts where the supply of vegetables was limited, the department distributed 13 tons of vegetable biscuits fortified with vitamin B flour.

Some genocide that.

In sum, relations between Canada and the Indigenous people have always been, and remain, complex. They have featured a continuum between enculturation and cultural assimilation, both voluntary. Occasionally, they involved the temporary legal suppression of traditional customs believed to be wasteful or inhumane. But in making sweeping assertions about forced assimilation and physical genocide, Pope Francis has distorted and defamed the history of Canada’s relations with its Indigenous people. In doing so, he has committed a grave injustice against both his own church’s clergy and the Indigenous people they were trying to help cope with the challenges of a rapidly evolving Canadian society.

Note also that the aim of the Catholic apologies was to achieve reconciliation with the country’s Indigenous peoples. But this has never occurred. No repentance was necessary not only because the recrimination was largely unfounded but because it could never result in reconciliation. Reconciliation is impossible because the mainly false allegations made against the Church are aimed only at employing guilt and shame to exhort endless financial and other compensation that Phil Fontaine Indigenous stated people “did not need” for sins committed by a tiny handful of its members.

In particular, of the thousands of Indian Residential School workers living in the schools during the system’s 113 years of government-funded operation (1883-1996), only 15 were found guilty of sexual abuse, including a single a Catholic priest.

As one commentator has recently argued:

“With all the stories about sexually abusing priests, for example, one would expect their percentage of convicted offenders to be quite large. One would expect to find hundreds, or even thousands, of priests convicted of sexual crimes. In fact, there is only one priest and one Christian lay brother on that entire list of 31 convicted offenders for the 100+ years that the schools operated.

“And with the many stories of brutality by the nuns who worked at the Roman Catholic residential schools, one would expect to find a long list of convicted nuns. In fact, there are only two nuns on that list (both Indigenous.) They were convicted of being too aggressive when administering cod liver oil or feeding the students.”

Fast forward the present, four decades after most of these schools were closed, and the problems said to be associated with them have have never gone away.

In Manitoba, 91% of children under the care of a family services agency are Indigenous. Nationally, Indigenous children under 14 account for 53.8% of children in care, according to the 2021 census, despite representing less than 8% of children in that age cohort. This shows that the Aboriginal child welfare crisis is as intractable today as it was in the 1940s. If so, how can the Catholic Church’s involvement continue to be blamed for this tragic situation?

Alas, only outsiders can discuss such issues because the Catholic Church, an institution that did all it could to deliver the means for a better way of life for Indigenous children, cannot fight back for fear that this would label it as made up of callous and unrepentant Indian Residential School denialists.

Hymie Rubenstein is editor of REAL Indigenous Report. A retired professor of anthropology, he was a board member of and taught for many years at St. Paul’s College at the University of Manitoba, the only Catholic higher education institution in Manitoba and one endorsed by the Canadian Province of the Society of Jesus.

___

Thanks for reading. For more from this author, read Challenging the assertion that "The reality of Indian Residential Schools was neglect and abuse"

BREAKING NEWS:

A new long-form essay by Dr. M - Fulcrum and Pivot: The New Left Remaking of Toronto School Policy

James Pew has contributed a chapter to the new book Grave Error: How The Media Misled us (And the Truth about Residential Schools). You can read about it here - The Rise of Independent Canadian Researchers

Also, for more evidence of the ideological indoctrination in Canadian education, read Yes, schools are indoctrinating kids! And also, Yes, The University is an Indoctrination Camp!

There are now two ways to support Woke Watch Canada through donations:

1) By subscribing to the paid version of the Woke Watch Canada Newsletter for - $7 Cdn/month or $70 Cdn/year

2) By making a contribution to the Investigating Wokeism In Canada Initiative, which raises the funds necessary to maintain and expand Woke Watch Canada’s research and investigation into Dysfunctional Canadian School Boards, Education, Indigenous Issues, Free Speech, and other areas of Illiberal Subversion and the Canadian Culture Wars.

This is the best article I have come across yet on real residential schools. We hear so much about the phone charge of culture genocide. Dr. Rubenstein finds a hole in this hyperbolic charge and lists the many examples of cultural empowerment.

Another articulate and informative article by the master of critical enquiry. One would hope that if Hymie is ever arrested for "Residential School Denialism" that Greg Piasetzski will step forward to defend him.

“Those who will not reason, are bigots, those who cannot, are fools, and those who dare not, are slaves.”

― George Gordon Byron (Lord Byron)